Paper seals for envelopes with the text “We will persevere”

Copyright: Wien Museum

Partner: Wien Museum

The parliaments of the Central Powers were still manned by the old elites, who were unable to throw off the chains of war and continued to cling to the illusion of a victorious peace. Amongst the general population, by contrast, the long lists of the fallen, the ubiquitous presence of war invalids and the shortage of basic necessities made many question the sense of the war that they had initially welcomed so heartily.

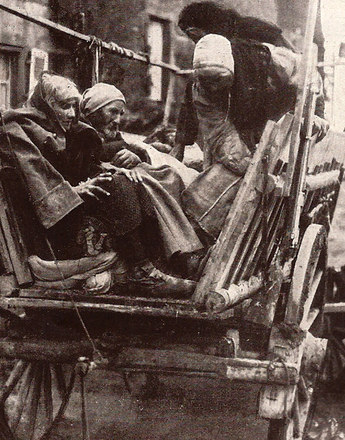

In the wake of the breakdown of the supply system in Austria-Hungary large sectors of the population lost their sense of orientation and fell into a state of apathy. Now that it was ever more difficult to acquire the basic necessities of life, people closed their ears to the clamour of the war propaganda and were deaf to the voices urging them to hold their heads up in the face of adversity. Beneath the calm surface, however, discontent was beginning to brew.

One of the state’s principal last resorts was to call in the military. Soldiers did not only fight at the front but were also used in so-called ‘assistance operations’ in the hinterland when public order needed to be kept. Uprisings, hunger protests and plundering were countered with great brutality, so that revolutionary tendencies would be firmly nipped in the bud. However, even in the army it was not always possible for order to be maintained. Desertion was common and in February 1918 there was a revolt amongst the naval troops on ships lying at anchor in the bay of Kotor (then in Dalmatia, now Montenegro), which was followed by further local mutinies in various parts of the Monarchy.

The government responded to the exacerbation of the problems by intensifying its authoritarian course, taking characteristically police-state measures and limiting civil rights. In the field of workers’ rights in particular there were stringent measures such as the prohibition of strikes, the raising of the working week to sixty hours, and cuts in wages. Extreme measures were taken in the armaments industry, where the workers were put under a strict military regime.

On the other hand, the government tried to compensate for their repressive measures by making concessions in the sphere of social change, through the Rent Restriction Act, for example, with its freezing of rents at pre-war levels. Measures in accordance with the ideal of social partnership such as the involvement of workers’ representatives gave the workforce a greater feeling that its contribution to keeping the state going was being recognized.

On the left wing of the political spectrum the longing for peace was accompanied by the desire for radical social change, for which there was a ready model in the Russian revolution and the downfall of the Tsarist regime. The spectre of Socialism caused the traditional elites of the nobility and upper middle classes to fear that history might take a similar course in Austria.

After pro-Soviet demonstrations in November 1917, January 1918 saw the Socialists and the left wing of the Social Democrats issuing calls for united political action. These struck such a chord in the hearts of the working people that over 700,000 workers from all the nationalities of the Monarchy joined forces in a general strike.

Translation: Peter John Nicholson

Hanisch, Ernst: Der lange Schatten des Staates. Österreichische Gesellschaftsgeschichte im 20. Jahrhundert [Österreichische Geschichte 1890–1990, hrsg. von Herwig Wolfram], Wien 2005

Hirschfeld, Gerhard/Krumeich, Gerd/Renz, Irina (Hrsg.): Enzyklopädie Erster Weltkrieg. Aktualisierte und erweiterte Studienausgabe, Paderborn/Wien [u.a.] 2009

Leidinger Hannes/Moritz, Verena: Der Erste Weltkrieg, Wien [u.a.] 2011

Rauchensteiner, Manfried: Der Erste Weltkrieg und das Ende der Habsburgermonarchie 1914–1918, Wien u. a. 2013

-

Chapters

- The course of the war 1917–1918: Face-to-face with imminent downfall

- The situation in the hinterland

- Apathy and resistance – The mood of the people

- The Sixtus Affair: A major diplomatic débacle

- A programme for world peace – President Wilson’s Fourteen Points

- ‘To My faithful Austrian peoples’ – Emperor Karl’s manifesto

- The collapse

- The disintegration of the Habsburg Monarchy – Part I: On the road to self-determination

- The disintegration of the Habsburg Monarchy – Part II: The situation in Vienna and Budapest

- The last days of the Monarchy