Martin Mutschlechner

“Viribus unitis” or prison of nations?

The multi-ethnic Austria-Hungary formed a relatively stable environment for the co-existence of the many ethnic communities. The much-vaunted “unity in diversity” was in fact overshadowed by numerous inequalities. This was illustrated above all in the differing weight of the various language groups involved in political and economic rule. These inequalities were increasingly challenged by the disadvantaged nationalities. As a result, the nationality issue dominated political affairs, leading to destabilisation of the Monarchy.

The Habsburg empire

Austria-Hungary had an extremely diverse state structure. At the start of the First World War it was a major power in decline. Social and political problems and the dominant nationality conflicts shook the empire to its foundations. At the same time, the Monarchy represented an enormous cultural region in which the Habsburg empire flourished in spite of the political stagnation.

The Fall of the Symbols of Habsburg Rule

The destruction of symbols of foreign domination – including the Column of the Virgin Mary in Prague and the Maria-Theresa Monument in Bratislava – gave expression to a sense of victory over national suppression and of newly achieved independence. But another interesting aspect of these actions is the “afterlife” of these historical monuments and the public treatment of them in the years after 1989.

The Czechoslovakian Legions

A special role in the creation of Czechoslovakia was played by the Czechoslovakian legions fighting at the side of the Entente armies. These legions consisted of voluntary units of émigré Czechs, but mostly of defectors and prisoners of war from the ranks of the Imperial-Royal Army.

The Czechoslovakian Republic as Successor State to Austria-Hungary

The acknowledgement of the Czechoslovakian Republic according to international law took place through the Paris Suburb Contracts of 1919/20. Czechoslovakia covered around 20% of the area of the former Monarchy and was thus the largest of the successor states.

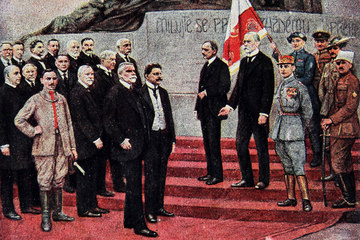

The Founding of Czechoslovakia

While the events in Prague were catapulting the country into a historic new phase, the home team of leaders was in Geneva to discuss further steps towards independence with the general secretary of the exiled Czechoslovakian National Council, Edvard Beneš. It was only by reading the newspapers that these gentlemen first learned that an independent Czechoslovakia had been proclaimed in Prague.

The Day of the Coup: 28 October 1918

After consensus had been achieved in Czech national society on overcoming the heteronomy, the task now was to take concrete steps for change. But the plans of the political leaders were thwarted by the dizzying momentum of events.

Preparing for the Coup

When concrete steps for a coup d’état were being taken in Prague in autumn 1918, the protagonists were surprised at the passivity shown by the organs of government, exposing the inner exhaustion of the old system and the lack of orientation in the Viennese central government. The sole objective seemed to be the avoidance of a violent escalation.

The aim of state independence: from Utopia to a programme for the masses

The loss of authority in the organs of government happened at breakneck speed (particularly in the sight of the failure to provide for people’s everyday needs) and created a vacuum into which the advocates of Czech state independence could penetrate. This originally avant-gardist idea became a feasible option for more and more people as the year 1918 wore on.