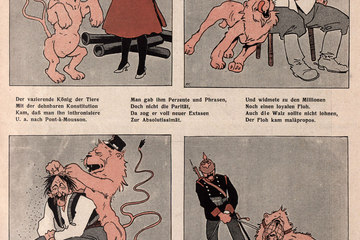

The place-names battle

In a multi-ethnic state like the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, the language and the spelling of place names in official usage was a hotly discussed issue, since they could be used to mark "national property". It sparked off a bitter struggle particularly in the multilingual regions.