In a multi-ethnic state like the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, the language and the spelling of place names in official usage was a hotly discussed issue, since they could be used to mark "national property". It sparked off a bitter struggle particularly in the multilingual regions.

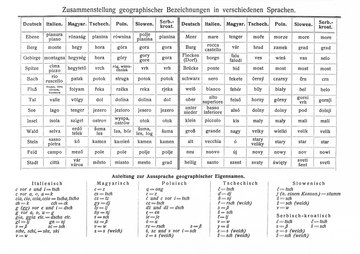

In the Habsburg Monarchy, many language groups lived in close contact with each other, which meant that there were often different versions of place and other topographical names. At times, the spellings differed only marginally, but they could also be completely different. In addition, in the east and south-east of the Empire, the question also arose whether the place names should be written in Latin or Cyrillic lettering.

While for instance in the case of Prague, the alternatives Prag (Germany), Praha (Czech), Prága (Hungarian) or Praga (Italian, Slovene, Polish etc.) were relatively easily recognised as the Bohemian capital, this was not so clear in other cases. Thus very different names have formed for Vienna in the various languages. The imperial capital and residence was called Vídeň by the Czechs, Viedeň by the Slovaks, Wiedeń by the Poles and Відень by the Ruthenians, while the Hungarians (Bécs), Croatians (Beč) and Serbs (Беч) used a completely different name. The Slovenes in turn developed their own name for the city, Dunaj, which in the Romance languages is known as Vienna (Italian) or Viena (Rumanian).

In the light of the constitutional principle of the equality of the nationalities, the state authorities as a matter of principle respected the demands for a topography in the national languages. Accordingly, multilingual place names were typically used on official documents, rubber stamps etc. At the same time, a certain degree of pragmatism was applied in order to ensure the uniformity of bureaucratic procedures. Thus in internal official post, army or railway communications, the German form of the place name – if it existed – was decisive.

In an age of raging nationalism, the question of the spelling of the topographical names at local level became a disputed issue. An extreme case was the Austrian Littoral, where one and the same place had names in German, Italian, Slovene, Croatian and other languages, such as in the case of the town of Gorizia, referred to as Görz by German-speakers, as Gorica by Slovenes and as Gurize by the Friulians. Even where the various versions were used in parallel, the sequence was discussed. Whether Italian was placed before the Slovene version or vice versa was already an indication of the various national claims to the place.

The attempts at a settlement were challenged by the demands of nationalistic extremists who – ignoring the name forms in the minority languages – would only tolerate monolingual names in the language of the majority nationality. However, this was only successful in Hungary, where after 1900 only the Hungarian version of the place name was used in official documents, irrespective of the local nationality conditions.

Translation: David Wright

Kann, Robert A.: Zur Problematik der Nationalitätenfrage in der Habsburgermonarchie 1848–1918, in: Wandruszka, Adam/Urbanitsch, Peter (Hrsg.): Die Habsburgermonarchie 1848–1918, Band III: Die Völker des Reiches, Wien 1980, Teilband 2, 1304–1338

Stourzh, Gerald: Die Gleichberechtigung der Nationalitäten in der Verfassung und Verwaltung Österreichs 1848 bis 1918, Wien 1985