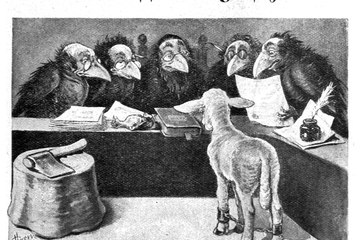

The First World War – child’s play

As the war increasingly made its presence felt in children’s everyday life, it also began to appear in the games they played. The general militarization of society also took hold in the nation’s nurseries. Role-play strengthened emotional ties with the aims of the war, while board and card games conveyed propaganda messages.