The outbreak of the First World War saw a change in accepted gender roles. Where there had previously been an opposition of masculine/public and feminine/private, a new form of differentiation emerged, defining the front as masculine and the home(land) as feminine.

The traditional division of gender roles, with men in public life and women in private, or family, life, had already begun to erode before the start of the war. Many women had jobs or other pursuits outside of the home. Furthermore, the women’s organizations that had been established attracted increased public attention to the interests and opinions of women.

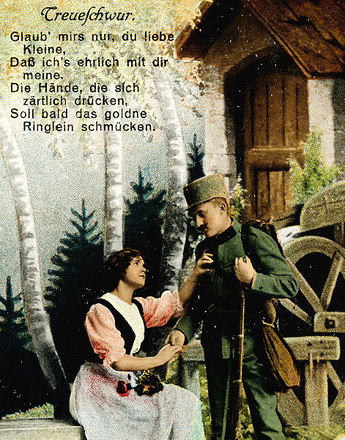

The start of the war, however, saw a new polarization of gender roles, which defined the front as a solely masculine domain, and the home(land) as a feminine one. In the realit(ies) of war, masculinity and femininity once again became complementary attributes. While the soldier on the front became a symbol of true masculinity, it was women engaged in war welfare efforts on the ‘home front’ who represented the epitome of femininity. They were to put their ‘natural’ virtues – motherliness and care – to the service of the Fatherland, or of the war.

The organization Frauenhilfsaktion im Kriege [Women’s War Assistance] also invoked women’s ‘universal virtues’ and ‘motherly instinct’ as a way to minimize class and religious divisions between its members. The organization collected donations for the soldiers on the front, helped women to find work, established war kitchens and set up sewing workshops where unemployed women could earn a little money by making clothing for the war effort. All of these activities were seen as ‘acts of love’ by the state.

To provide moral support to the soldiers, women and children prepared small parcels containing hand-knitted socks and winter hats, chocolate, tobacco and dried fruit. These packages were then sent to the front as ‘alms’, referred to in German as ‘Liebesgaben’, or ‘gifts of love’. In this love discourse, an (apparent) link or relationship was created between the anonymous soldiers and the women and girls back home.

Margarete Feuerbach, who was born in Vienna in 1905, still remembered decades later the names of the soldiers she sent parcels to:

Depending on how much we could afford, we had to put together parcels of food, like chocolate, dried fruit, crackers and cigarettes, and send them to the soldiers at the front. I was also allowed to send one of these parcels, and I was very proud when one day, I got a card from a soldier at the front, thanking me for my parcel. I still remember his name to this day: Anton Blecha.

Women’s selfless readiness to help and their caring nature were seen as a significant contribution to the war effort. For the soldiers, the image of the tender, loving mother was the embodiment of home. This image conflated the women back home into one homogenous mass whose love represented the antithesis of the war being waged by the men.

Translation: Aimee Linekar

Daniel, Ute: Frauen, in: Hirschfeld, Gerhard/Krumeich, Gerd/Renz, Irina (Hrsg.): Enzyklopädie Erster Weltkrieg, Paderborn et al. 2009, 116-134

Hämmerle, Christa: „Wir strickten und nähten Wäsche für Soldaten…“ Von der Militarisierung des Handarbeitens im Ersten Weltkrieg, in: L´Homme. Zeitschrift für Feministische Geschichtswissenschaft (1992) 1, 88-128

Hämmerle, Christa: „Habt Dank, Ihr Wiener Mägdelein…“ Soldaten und weibliche Liebesgaben im Ersten Weltkrieg, in: L´Homme. Zeitschrift für Feministische Geschichtswissenschaft (1997) 1, 132-154

Hämmerle, Christa: „Zur Liebesarbeit sind wir hier, Soldatenstrümpfe stricken wir …“ Zu Formen weiblicher Kriegsfürsorge im Ersten Weltkrieg (unveröffentlichte Dissertation), Wien 1996

Healy, Maureen: Vienna and the Fall of the Habsburg Empire. Total War and Everyday Life in World War I, Cambridge 2004

Heeresgeschichtliches Museum: Die Frau im Krieg. Katalog zur Ausstellung vom 6. Mai bis 26. Oktober 1986, Wien 1986

Quotes:

"Depending on how much we could afford …“: Margarete Feuerbach, Kindheitserinnerungen. 1. Weltkrieg. 2. Weltkrieg, unveröff. Manuskript der Dokumentation Lebensgeschichtlicher Aufzeichnungen der Universität Wien, dat. 1985, quoted from: Hämmerle, Christa: „Wir strickten und nähten Wäsche für Soldaten…“ Von der Militarisierung des Handarbeitens im Ersten Weltkrieg, in: L´Homme. Zeitschrift für Feministische Geschichtswissenschaft (1992) 1, 108 (Translation)