The ideal of the thrifty housewife

In view of the supply crisis, food gained political importance. Women, upon whom fell in most cases the feeding of their families, became protagonists of a morally highly stylised, existential provision. Through thriftiness and ingenuity they were supposed to conquer the foe in the kitchen.

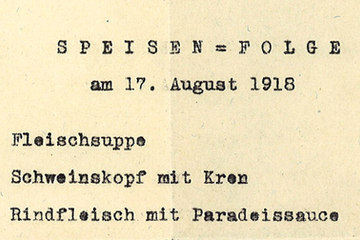

On account of the war economy, the provision of foodstuffs became a symbol battlefield. Anglicisms and words of French origin disappeared from the menu and women were called upon to do justice their enthusiasm for the war as consumers too, and to boycott foreign goods.

When the blockade policy against the Central Powers began, the threat of ‘hunger war’ turned into an effective argument for mobilisation. The target in the first instance was the woman, upon whom fell in most cases the task of ensuring their family survived day by day. The rhetoric of mobilisation linked the ‘skill of the thrifty housewife’ with the fate of the nation: the functioning of the war economy was to depend upon their housewifely creativity, above all upon their willingness to make sacrifices. This creation of meaning is made clear in the introduction to the ‘Little Cook Book in Times of Need’, published in Vienna in 1916. Thus writes the author Ida Schuppli, for example:

‘The war with its side-effects has everywhere influenced the running of the household in a comprehensive way. Feeding ourselves has become more difficult by the day. It has presented us housewives with tasks which are of decisive importance not just for our families, but also for the whole nation. […] Despite the lack of food, we have to search for it [food, note] in such a creative way that our people’s power suffers as least as possible in these troubled times. If we succeed in fulfilling this high mission, then not only will we have wrecked our enemies’ plan to starve us, but also we shall preserve our people and fatherland from misfortune, and prove ourselves to be good mothers and citizens.’

If women succeeded in challenging the existence of their family by means of careful economising, thrifty housekeeping, and through skill and ingenuity, then they were assured of social recognition. Economical housekeeping turned into a duty that could decide the war. However, if women acted against the interests of the war economy, and sent prices to astronomical heights due to hamster purchasing, then the reproaches rained down on them.

The ideology of ‘joint responsibility’ conveyed an unmistakable message: the victims at the home front were of secondary importance and not to be compared with those on the front. To hold on and to compensate for the shortages was the very least that could be demanded from the population.

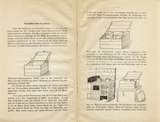

This message was spread by propaganda material as much as through patriotic women’s associations: hiking talks, exhibitions and cooking courses conveyed both knowledge and skills in how to make up for the extreme privations. War recipes affixed to the back of tram tickets taught how to use surrogates in a thrifty way; women trained their members in how to make box cookers that were fuel-efficient; and in ‘test eating’, plants hitherto designated unpalatable were tested as possible substitutes.

In the third year of the war the initial enthusiasm finally gave way to disenchantment. The state authorities were no longer able to provide a sufficient supply of basic foods and daily life could only be overcome by means of extreme sacrifice. Living costs had risen many-fold (by 1918 they were 13 times pre-war levels) and a sufficient level could not be reached with the rations allocated. Under these conditions, the civilian population was no longer prepared to see their sacrifice as of secondary importance. They placed their privations on an equal footing with the suffering of the soldiers.

Augeneder, Sigrid: Arbeiterinnen im Ersten Weltkrieg. Lebens- und Arbeitsbedingungen proletarischer Frauen in Österreich, Wien 1987

Bauer, Ingrid: Frauen im Krieg. Patriotismus, Hunger, Protest – weibliche Lebenszusammenhänge zwischen 1914 und 1918, in: Mazohl-Wallnig, Brigitte (Hrsg.): Die andere Geschichte, Bd. I Eine Salzburger Frauengeschichte von der ersten Mädchenschule (1695) bis zum Frauenwahlrecht (1918), 285-310

Healy, Maureen: Vienna and the Fall of the Habsburg Empire. Total War and Everyday Life in World War I, Cambridge 2004

Healy, Maureen: Vom Ende des Durchhaltens, in: Pfoser, Alfred/Weigl, Andreas (Hrsg.), Im Epizentrum des Zusammenbruchs. Wien im Ersten Weltkrieg, Wien 2013, 132-139

Quotes:

„Der Krieg mit seinen Begleiterscheinungen...“: Schuppli, Ida/Hinterer, Betty: Kochbüchlein für knappe Zeiten. Mit einer Anleitung zum Einkochen der Früchte ohne und mit wenig Zucker, zum Dörren, Einsäuern und Einwintern von Obst und Gemüse. Ein Anhang zum Grabnerhof-Kochbuch, Wien 1916, Vorwort