-

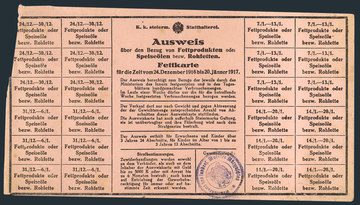

Leaflet concerning the issue times of ration cards

Copyright: Heeresgeschichtliches Museum, Wien

Partner: Heeresgeschichtliches Museum -

Krawalle auf dem Yppenplatz in Wien, Zeitungsillustration aus Illustrierte Kronenzeitung, Ausgabe vom 30. Juli 1914

Copyright: Wienbibliothek im Rathaus

Partner: Universitätsbibliothek Wien

In October 1914, just a few months after the war began, shortages and scarcities could be felt everywhere. The authorities thus took the first measures in terms of rationing and intervention.

The population reacted to the worsening supply situation with hamster-style hoardings and panic buying. The sinking supply and rising demand, furthered by massive food purchasing on the part of the military, led to horrendous price hikes and some traders holding back their goods in order to speculate.

To defuse the situation and to avoid unrest, the government took intervention measures in the late summer of 1914. Regulations were passed which forbade the hoarding of food, the stretching of flour stocks with cheaper sorts of grain, and which tightened punishments against profiteering. Yet the required effect failed to materialise: the stocks quickly ran out, products became scarcer by the week and painfully more expensive.

Demands from the population for capped pricing could be heard, which the government gave in to in November 1914. In practice, however, these upper limits developed into minimal prices, and traders continued to withhold their products or to sell them on the black market at a multiple of the regular prices. While regular prices in the food sector rose ten-fold up to 1918, prices in illicit trade and the black marketing soared to well over the 1000 percent mark. If one kilogramme of flour still cost 44 hellers (Austrian currency) in 1914, by autumn 1918 the regular price for the same had soared to 2.76 crowns. At the same time, the kilogramme was traded on the black market for 30 crowns. A similar price progression emerged with animal products: here the regular price for a kilogramme of butter rose from 3.20 crowns to 20.60 crowns, while the illicit market price hit 120 crowns meanwhile. If an egg could be purchased at the beginning of the war for 9 hellers, by autumn 1918 the same item was traded on the black market for 40 crowns.

To counteract illicit trading, and to ensure uniform management with strategically important goods, the government set up so-called ‘Centrals’. The creation of a metal ‘central’, a wool ‘central’, an animal feed ‘central’, a war coffee ‘central’ etc. was meant to remove scarce goods from private consumption, and to place it at the disposal of state distribution authorities.

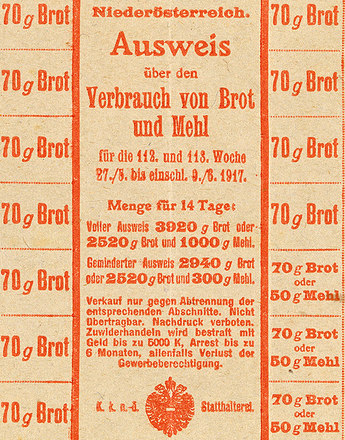

When the population reacted once again to non-delivery of bread and flour in January 1915 with panic buying, the War-Grain-Commerce-Institution was the first to introduce the ration book system in April. In this way the state extended the control system of distribution at fixed prices to the allocation of fixed amounts. Per capita quotas were set and distributed by means of bread and flour cards.

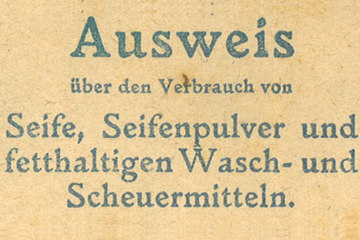

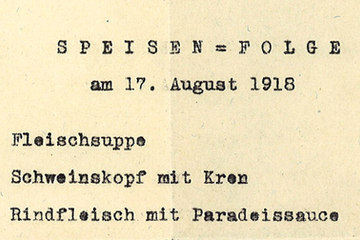

Gradually the card system was extended to other foodstuffs, too: in 1916 the rationing of sugar, milk, coffee and fat followed, and later on that of potatoes, meat and jam. Alongside this, there existed so-called purchase notes, by means of which the purchase of products such as cheese, eggs and rice was regulated. The food cards were given out according to three categories and differentiated between self-providers (agricultural producers), non-self-providers (the urban population) and heavy workers (pooled together in this category were industrial workers, railway employees and security officials). The drastic worsening of the food situation is shown in the development of the daily allocation of calories: while heavy workers had at least 1,725 calories, and non-self-providers 1,300 calories daily, the allocated quota eventually sank to 1,290 and 830 calories per day respectively.

The number of confiscated and state-registered foodstuffs and substitutes were permanently extended, the pro-capita quotas successively cut. Yet state control of managing the economy proved to be inefficient and formed fertile soil for a shadow economy that was gaining the upper hand: illicit trade, receiving stolen goods, profiteering, grafting and hamster-style purchasing were among the most common economic crimes.

In November 1916 great hope was placed in the newly created Office for Feeding the People. This was intended to bring together and strategically direct the various rationalisation measures. The office’s main task was to register stocks of food, to distribute them justly among consumers, and to ensure fair pricing. In reality, however, it was only entrusted with managing the shortages. Misery and deprivation could no longer be got to grips with by means of state interventionist measures.

Ackerl, Isabella (Hrsg.): Hans Loewenfeld-Russ- Im Kampf gegen den Hunger. Aus den Erinnerungen des Staatssekretärs für Volksernährung 1918–1920, Wien 1986

Broadberry, Stephen/Mark Harrison, The Economics of World War I, Cambridge 2005

Hautmann, Hans: Hunger ist ein schlechter Koch. Die Ernährungslage der österreichischen Arbeiter im Ersten Weltkrieg, in: Botz, Gerhard et al. (Hrsg.): Bewegung und Klasse. Studien zur österreichischen Arbeitergeschichte. 10 Jahre Ludwig Boltzmann Institut für Geschichte der Arbeiterbewegung, Wien/München/Zürich, 1978, 661-682.

Rauchensteiner, Manfried: Der Erste Weltkrieg und das Ende der Habsburgermonarchie 1914–1918, Wien/Köln/Weimar 2013