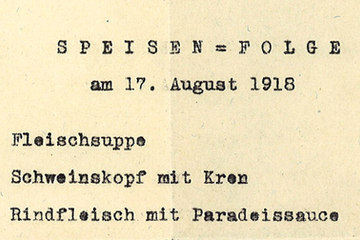

During the war, the civilian population came to endure a worsening of their living conditions in general. This affected the shortage in foodstuffs and consumer goods in a particularly drastic way, however, leading to a dramatic emergency.

On the eve of the First World War, the Danube Monarchy was broadly autonomous in terms of provision of food. The majority of the population worked in the agricultural and forestry sectors and could mostly meet its needs concerning animal products, grain, fruit and vegetables. In Hungary, where 67 percent of the working population was employed as subsistence farmers, it proved possible to ensure the grain consumption through domestic production and, moreover, to meet demand in Cisleithania. Meanwhile, the Austrian half of the empire depended in almost all sectors of agricultural production on imports from Hungary, and it was inconceivable that the population could be adequately supplied with the ‘corn and meat pantry’ of the Monarchy. This situation, good in peace time, changed instantly with the outbreak of war, and the material situation of the Habsburg Monarchy began to worsen dramatically.

The decisive factor was that, from the economic perspective, a long war was not anticipated. Those authorities concerned assumed a short and victorious conflict, and took hardly any precautionary supply measures. After the 1914 harvest yields fell short of expectations, on account of climatic conditions, Hungary reacted with export restrictions on agrarian products. Imports from Transleithania up to 1917 sank to 20 percent for meat stock, 3 percent for flour, and 2 percent for grain of the levels seen during peace time.

Agriculture in the Austrian half of the empire was unable to compensate for these shortfalls, especially as the total mobilisation led to a lack of workers, draught animals, seeds, animal feed and fertilisers. The crisis was exacerbated by the occupation of Galicia, hitherto an important supplier of agrarian products, by Russian troops. The fighting rendered the fields barren and both flight and expulsion brought about the collapse of agricultural production. Matters were made more difficult by disputes between the two halves of the Empire over distribution and where to focus in terms of industries vital for the war. Agricultural output suffered as a result, achieving only half of pre-war levels in 1917.

Due to the naval blockade imposed by the Entente, and the prohibitions on imports, exports and transit that gradually came into effect, production shortages could be made up for by imported goods. The exchange of wares on the domestic market and with neutral states was reduced. Yet due to the total mobilisation and transports to the various fronts, fewer and fewer trains operated in the hinterlands. Goods transportation was held up, the transport of wares could no longer be guaranteed, and raw materials as well as good vanished from the market as time went by.

Ackerl, Isabella (Hrsg.): Hans Loewenfeld Russ. Im Kampf gegen den Hunger. Aus den Erinnerungen des Staatssekretärs für Volksernährung 1918 – 1920, Wien 1986

Hautmann, Hans: Hunger ist ein schlechter Koch. Die Ernährungslage der österreichischen Arbeiter im Ersten Weltkrieg, in: Botz, Gerhard et al. (Hrsg..): Bewegung und Klasse. Studien zur österreichischen Arbeitergeschichte. 10 Jahre Ludwig Boltzmann Institut für Geschichte der Arbeiterbewegung, Wien/München/Zürich, 1978, 661-682

Langthaler, Ernst: Die Großstadt und ihr Hinterland, in: Pfoser, Alfred/Weigl, Andreas (Hrsg.): Im Epizentrum des Zusammenbruchs. Wien im Ersten Weltkrieg. Wien 2013, 232-239

Rauchensteiner, Manfried: Der Erste Weltkrieg und das Ende der Habsburgermonarchie 1914–1918, Wien/Köln/Weimar 2013

Schulze, Max-Stephan: Austria-Hungary´s economy in World War I, in: Broadberry, Stephen/Mark Harrison, The Economics of World War I, Cambridge 2005, 77-111