The undiminished desire for territorial expansion by the regional powers ensured that the Balkan crisis was an ever-present constant in Europe’s political affairs.

‘Let them bash their heads in; we’ll watch from the balcony.’

Quoted in Bled, Jean-Paul, Franz Ferdinand. Der eigensinnige Thronfolger (Vienna, 2013), p. 244

In spite of the return of the occupied Sanjak of Novi Pazar to the Ottoman Empire, the annexation of Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1908 isolated Austria-Hungary in south-eastern Europe. Vienna had finally turned Serbia into an enemy, and relations with Russia were at a low point. The unconsidered action also brought the disputative Balkan states closer together. Under Russian patronage they formed an alliance for the division of the European part of Turkey, once again aggravating the situation in the Balkans.

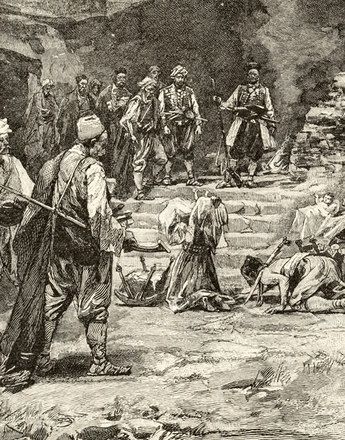

The First Balkan War in 1912/13 was a war of aggression by the young nation states of Serbia, Montenegro, Bulgaria and Greece against the internationally isolated Ottoman Empire and resulted in the loss of its territories in the Balkan peninsula. The conflict was also a proxy war between the major powers, which indirectly acted out their rivalry through treaties of alliance. A war between Serbia and Bulgaria in the summer of 1913 further complicated the situation in the Balkans.

After Serbia had asserted all of its possible territorial claims against the Ottoman Empire, it set it sights on the Habsburg Monarchy, which in the eyes of Belgrade had already become the greatest obstacle to the goal of a greater Serbia through its annexation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, thereby occupying a territory that in Serbian national propaganda was styled as a ‘primeval component of Serbianness’. Revolutionary nationalist circles among the Serbian intelligentsia vehemently demanded the amalgamation of the southern Slav regions of the Habsburg Monarchy with Serbia. One organization devoted to this idea was the school and university fraternity Mlada Bosna (Young Bosnia), one of whose members would be the future assassin of Sarajevo, Gavrilo Princip.

The long-term aim was a southern Slav empire from the Adriatic to the Black Sea led by the Serbs as the most populous nation in the region. Within a few decades Serbia had developed into an important regional power. An interesting variant in the furore of nationalist enthusiasm was the idea of a national Serbian military dictatorship proposed by extreme nationalists in the army. Radical underground organizations like Ujedinjenje ili smrt (Unification or Death) – better known as Crna Ruka (Black Hand) – undermined the state authority with the aim of eliminating supposed ‘enemies of the people’ by means of terrorist acts.

Austria-Hungary reacted openly to the Serbian expansionist designs. Vienna presented itself as the custodian of the balance of power in the Balkans and as a bulwark against the escalating nationalism of the Balkan peoples. Austria’s anti-Serbian policy gained a victory with the establishment of Albania as an independent state in 1912/13. This measure was aimed above all at containing Serbia’s rise, since it denied Belgrade, which had long had designs on this region, access to the Mediterranean.

This was the only ‘success’ in Austria’s Balkan policy. The international crisis provoked by Austria-Hungary through the annexation of Bosnia and Herzegovina had created a massive shift in the balance of power in the Balkans both among the Balkan states themselves and between the major powers, which had been drawn into the turmoil on account of their various treaties of alliance. In this unstable situation the assassination of the Austrian heir to the throne in Sarajevo was the proverbial spark that caused the powder keg to explode.

Translation: Nick Somers

Bihl, Wolfdieter: Der Erste Weltkrieg 1914–1918. Chronik – Daten – Fakten, Wien/Köln/Weimar 2010

Buchmann, Bertrand Michael: Österreich und das Osmanische Reich. Eine bilaterale Geschichte, Wien 1999

Džaja, Srećko: Bosnien-Herzegowina in der österreichisch-ungarischen Epoche (1878–1918) (Südosteuropäische Arbeiten 93), München 1994

Hösch, Edgar: Geschichte der Balkanländer. Von der Frühzeit bis zur Gegenwart, München 1999

Rumpler, Helmut: Eine Chance für Mitteleuropa. Bürgerliche Emanzipation und Staatsverfall in der Habsburgermonarchie [Österreichische Geschichte 1804–1914, hrsg. von Herwig Wolfram], Wien 2005

-

Chapters

- Under the crescent: the Ottoman Empire and Europe

- ‘The Sick Man of Europe’ – a major power in decline

- The ‘Balkanization’ of the Balkans – the nuisance of popular freedom struggles

- Bosnia and Austria’s aspirations in the Balkans

- The Congress of Berlin and the division of the Balkans

- The 1908 annexation crisis

- The 1912/13 Balkan crisis – prelude to world war