The Congress of Berlin failed to bring about a lasting solution in the Balkans. Behind the façade of a laboriously maintained peace, the old conflicts continued to simmer. Austria-Hungary’s ambitions as a major power were also focused on the Balkans as a means of pasting over the problems at home with a demonstration of strength abroad.

Austria-Hungary expanded its influence in the Balkans during the 1880s. Under the pro-Austrian Obrenović dynasty, Serbia became a satellite state with great economic dependence on Vienna. For Romania, Austria was an ally who would defend against Russia’s desire for expansion on Romanian territory in the Black Sea region. For the Habsburg Monarchy, the friendly relations with these states offered welcome relief from domestic nationality problems, since the foreign policy alliance weakened the Serb and Romanian separatist movements in Hungary. The issue remained oppressive, however, because the continuing discrimination against the Serbian and Romanian language groups in the Hungarian half of the empire was not going to be ignored forever by their respective motherlands.

A dramatic change took place in Serbia in 1903 when King Alexander Obrenović was assassinated in a coup d’état. The new ruler, King Peter I from the Karađorđević dynasty, pursued a greater Serbia and pro-Russian course. This had grave consequences for relations with Austria-Hungary. Vienna responded initially with economic sanctions. After Serbia cancelled a major order with the Škoda works and awarded it instead to a French company as an indication of its rapprochement with France, Austria-Hungary imposed a trade embargo on Serbia (‘Pig War’), which plunged the Serbian economy, reliant as it was on agrarian exports, into a deep crisis.

This led to a fatal development in Balkan politics. Russia again claimed supremacy for itself in the region. Italy entered the arena with an expansionist Balkan policy aimed at Albania. Austria-Hungary also stepped up its ambitions in the Balkans in 1906, once again as a means of covering up and possibly resolving the domestic crisis.

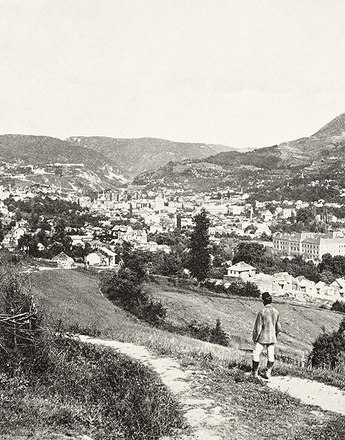

These activities culminated in 1908 in the annexation of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Intended as a catalyst for domestic policy, it proved to be a fateful move. The incorporation of Bosnia and Herzegovina in the Dual Monarchy created an insoluble problem between the two halves of the empire. As they were unable to reach an agreement as to which half should acquire the territory, by way of a compromise, Bosnia and Herzegovina became a condominium administered by the joint Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

The consequences for foreign policy were even more serious. Although the annexation was merely the appropriation of a territory that was already de facto part of the Monarchy, it was seen internationally and constitutionally as an act of aggression in violation of international treaties.

Serbia and Russia interpreted it as a provocation and threatened war. The situation was saved only when Germany demonstratively supported Austria-Hungary, making Vienna even more dependent on Berlin. The Austrian Balkan policy had put the Monarchy in a tricky situation leading to the brink of war. Some army leaders even welcomed a military solution in the form of a ‘preventive war’, and Austrian chief of general staff Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf openly advocated a ‘settling of accounts with Serbia’.

Translation: Nick Somers

Bihl, Wolfdieter: Der Erste Weltkrieg 1914–1918. Chronik – Daten – Fakten, Wien/Köln/Weimar 2010

Buchmann, Bertrand Michael: Österreich und das Osmanische Reich. Eine bilaterale Geschichte, Wien 1999

Džaja, Srećko: Bosnien-Herzegowina in der österreichisch-ungarischen Epoche (1878–1918) (Südosteuropäische Arbeiten 93), München 1994

Hösch, Edgar: Geschichte der Balkanländer. Von der Frühzeit bis zur Gegenwart, München 1999

Rumpler, Helmut: Eine Chance für Mitteleuropa. Bürgerliche Emanzipation und Staatsverfall in der Habsburgermonarchie [Österreichische Geschichte 1804–1914, hrsg. von Herwig Wolfram], Wien 2005

-

Chapters

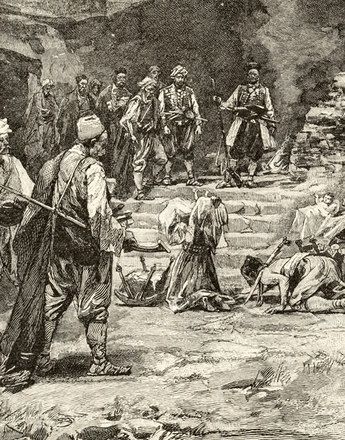

- Under the crescent: the Ottoman Empire and Europe

- ‘The Sick Man of Europe’ – a major power in decline

- The ‘Balkanization’ of the Balkans – the nuisance of popular freedom struggles

- Bosnia and Austria’s aspirations in the Balkans

- The Congress of Berlin and the division of the Balkans

- The 1908 annexation crisis

- The 1912/13 Balkan crisis – prelude to world war