The government in Vienna sought to prevent Russia from establishing itself as the protector of the orthodox Balkan Slavs. The Habsburg Balkan policy therefore aimed at strengthening the Austrian presence in the Balkan ‘powder keg’. It was thwarted in doing so by the rise of Serbia as a regional power.

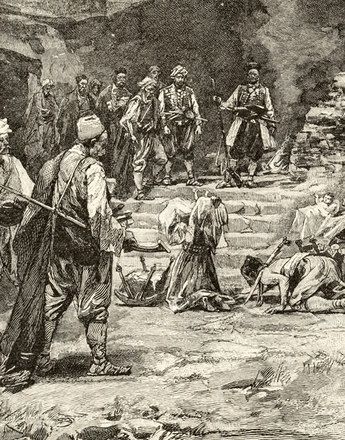

The growing significance of Serbia, which had gradually liberated itself from Ottoman sovereignty, made the young state increasingly aggressive in its demand for the ‘return’ of supposedly ‘Serbian soil’. Serbian irredentism led to armed uprising by Bosnian Serbs against the Ottoman rulers in Bosnia. This feud by local separatists with the Ottoman provincial government was openly supported by Serbia, Montenegro and Russia.

A revolt in Herzegovina in 1875 developed in this way into a war of liberation by the Serbs under Ottoman rule, supported by the already de facto independent young states of Serbia, Romania and Greece. The supposedly weak Ottoman regime showed its strength, however, and it took energetic intervention by the Russians to save the Serbs from disaster. Taking advantage of the situation, Russia launched a further military intervention in 1877 with the aim of driving the Ottomans out of the Balkans and of establishing a ‘greater Bulgarian empire’ as a Russian satellite state in the eastern Balkans.

As a reaction to the Russian ambitions, Austria-Hungary felt coerced to strengthen its position as a regional major power in the western Balkans. Apart from hopes of additional territory, the government in Vienna saw the intervention as a way of turning southern Slav nationalism into a pro-Austrian movement. Franz Joseph communicated his support to the Sultan, and Vienna profiled itself on the international stage as the ‘knight in shining armour’ arriving to put an end to the ‘Balkan chaos’. Vienna offered its Ottoman partner ‘development aid’ in the form of assistance in expanding the infrastructure and in mapping the western Balkans. This was not an entirely altruistic endeavour because it enabled Austrian strategists to obtain precise information about the lie of the land in that region.

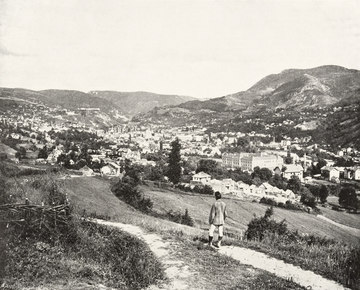

The Foreign Ministry in Vienna officially denied that it had any aspirations to expand into Bosnian territory, but internally it prepared for an invasion. The army leadership was also in favour of Austria-Hungary’s expansionist policy in the Balkans, because in the event of a crisis Dalmatia would have been far too exposed and difficult to defend. Bosnia and Herzegovina would function as a land bridge, since parts of southern Dalmatia could only be reached by sea. The economic development of Dalmatia would also be of utility only if the Bosnian hinterland were involved as well.

This colonial and imperialistic approach was typical of the final expansion phase by the major powers. The last ‘available’ territories were colonized, and within Europe the Balkans under the weak control of the ‘Sick Man of Europe’ was the final remaining territorial reserve. Emperor Franz Joseph was also in favour of expanding the Habsburg Monarchy to compensate for the loss of territory following the unification of Italy.

To gain the agreement of the major European powers for the occupation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, imperial diplomacy on the international stage was needed to protect Austria, since this step was likely to involve a serious conflict with Russia. The forum was the Congress of Berlin in 1878, at which the division of power in the Balkans was to be restructured.

Translation: Nick Somers

Buchmann, Bertrand Michael: Österreich und das Osmanische Reich. Eine bilaterale Geschichte, Wien 1999

Džaja, Srećko: Bosnien-Herzegowina in der österreichisch-ungarischen Epoche (1878–1918) (Südosteuropäische Arbeiten 93), München 1994

Hösch, Edgar: Geschichte der Balkanländer. Von der Frühzeit bis zur Gegenwart, München 1999

Rumpler, Helmut: Eine Chance für Mitteleuropa. Bürgerliche Emanzipation und Staatsverfall in der Habsburgermonarchie [Österreichische Geschichte 1804–1914, hrsg. von Herwig Wolfram], Wien 2005

-

Chapters

- Under the crescent: the Ottoman Empire and Europe

- ‘The Sick Man of Europe’ – a major power in decline

- The ‘Balkanization’ of the Balkans – the nuisance of popular freedom struggles

- Bosnia and Austria’s aspirations in the Balkans

- The Congress of Berlin and the division of the Balkans

- The 1908 annexation crisis

- The 1912/13 Balkan crisis – prelude to world war