-

Story The 'Balkan powder keg'

The ‘Balkanization’ of the Balkans – the nuisance of popular freedom struggles

In the nineteenth century, the Balkans were the setting for the growing emancipation endeavours of the various peoples in the region, where the seeds of the French Enlightenment and the nationalist ideology, as everywhere in Europe, fell on fertile ground.

The belated emergence of national identities compared with western Europe, together with the social and economic backwardness of the region, produced a flight from reality of sorts, which found expression in historically dressed-up power fantasies. The restoration of idealized and imagined medieval empires (‘greater Serbia’, ‘greater Bulgaria’, etc.) was seen as the way of overcoming all obstacles, but it also gave rise to aggressive claims to hegemony over other religious and linguistic groups.

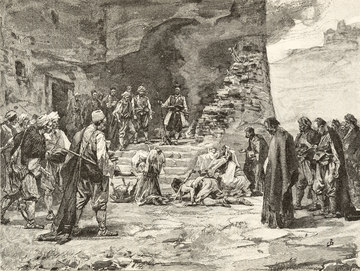

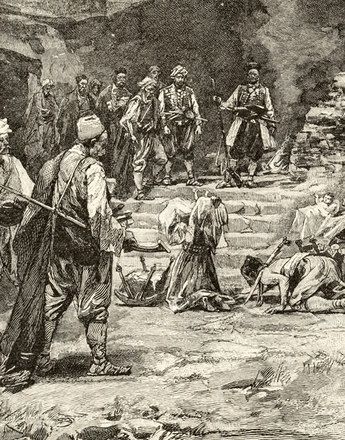

The only thing that united the young nation states in the Balkans, quarrelling with one another on account of their diverging nationalist aspirations, was their common animosity to the Turkish rulers, who were seen as being exclusively to blame for all their problems. The leaders of the emerging Serbian, Bulgarian and Romanian national societies now began to challenge the Turkish empire.

The Sultan did not have the means anymore to quell these separatist movements. As in the multinational Habsburg empire, he reacted with a combination of tolerance and repression, but the Sublime Porte was no longer able to preserve territorial unity. The Sultan’s authority at the fringes of the Ottoman Empire was often merely nominal, as real power was exercised there by local potentates. Istanbul was forced initially to recognized the limited independence of these territories. A wreath of vassal states emerged, which were obliged to pay tribute to the Sultan and remained formally under his suzerainty. Among these countries in the Balkan region were Serbia (from 1817), Wallachia and Moldova, which combined to form the principality of Romania in 1859/61, and finally Bulgaria (1878). The formation of these tributary states was a concession by the Sultan as a means of saving face after he had already lost real control over them. In the eyes of the young nations, however, this was only an intermediate step on the way to their long-term aim of complete independence from ‘Ottoman tyranny’.

Serbia played a special role in these independence movements. A number of popular Serbian revolts against the Ottoman rulers took place between 1804 and 1812. They vainly sought allies in a Europe buffeted by the Napoleonic Wars. Austria refused to intervene on Serbia’s behalf, pointing to its alliance with the Ottoman Empire. It was therefore left to Russia to support Serbian independence, ideologically underpinned by their common orthodox religious traditions.

Austria’s refusal to help promote Serbian statehood was due above all to the fact that Vienna saw an independent Serbian state as a danger to its own existence as a multinational state. It was obvious that the Serbs (and later the other southern Slavic ethnic groups) under Austrian rule would sooner or later demand association with the Serbian nation state. Austrian policies therefore aimed to contain the expansion of Serbia’s status as a regional power as far as possible.

Translation: Nick Somers

Buchmann, Bertrand Michael: Österreich und das Osmanische Reich. Eine bilaterale Geschichte, Wien 1999

Hösch, Edgar: Geschichte der Balkanländer. Von der Frühzeit bis zur Gegenwart, München 1999

Rumpler, Helmut: Eine Chance für Mitteleuropa. Bürgerliche Emanzipation und Staatsverfall in der Habsburgermonarchie [Österreichische Geschichte 1804–1914, hrsg. von Herwig Wolfram], Wien 2005

-

Chapters

- Under the crescent: the Ottoman Empire and Europe

- ‘The Sick Man of Europe’ – a major power in decline

- The ‘Balkanization’ of the Balkans – the nuisance of popular freedom struggles

- Bosnia and Austria’s aspirations in the Balkans

- The Congress of Berlin and the division of the Balkans

- The 1908 annexation crisis

- The 1912/13 Balkan crisis – prelude to world war