The enemy in film

The Austro-Hungarian film propaganda centred above all on the presentation of the imperial household and the military and economic strength. It was not just a question of outdoing the enemy but trying to match the over-representation of propaganda by allied Germany.

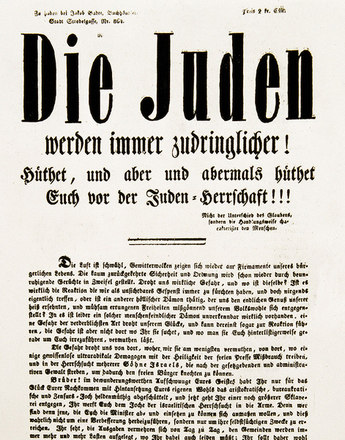

Direct attacks on the enemy were shown above all in cartoons. The Robert Müller distribution and production company began to make patriotic cartoons with the aid of Viennese graphic artist Theo Zasche. His mocking films often had anti-Russian and anti-Semitic content. In 1914, for example, he made the animated satire When the Russian Stood Before Przemyśl, a ‘short heroic epic by the Austro-Hungarian army against the Russian steamroller’. The Tsar and His Dear Jews appealed to the audience’s anti-Semitic instincts, and The New Triumvirate about the Moscow-Paris-London axis showed the three heads of state as malicious and hateful. Sascha-Filmfabrik also jumped on the cartoon bandwagon and hired Karl Robitschek, who operated under his screen name Rob. His works included The Sure Road to Peace (A 1917) and Us and the Others (A 1917). As the enthusiasm for patriotic cartoon films waned towards the end of the war, cinema owners were informed that it was their ‘patriotic duty’ to show political cartoons, which were ultimately distributed free of charge to the cinemas. None of the Austro-Hungarian war caricatures have survived.

The films by the Austro-Hungarian propaganda machine sought to present a positive picture and showed the enemy as a traitor, coward and weakling. In the film The Twelfth Battle of Isonzo (A 1917) the Italian units are seen running away and looking – obviously having been instructed to do so – at the camera. The pictures of prisoners of war moving slowly and in organized lines also look to be staged. The good treatment of the Italian soldiers was designed to show the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy in the best light to neutral countries. In reality, there were considerable problems in supplying the enormous fighting units with food.

Huge camps were created, and reports on terrible living conditions were heard particularly in the first years of the war. The situation in the camps improved later, not least because many prisoners were put to work in the war economy. In Austria-Hungary in 1917 some 660,000 mostly Russian prisoners worked in agriculture or factories and almost 300,000 with the army in the field. Films like Building of an Austrian Armaments Factory by Russian Prisoners of War (A c. 1915) show internees at work.

Translation: Nick Somers

Leidinger, Hannes/Moritz, Verena: Gefangenschaft, Revolution, Heimkehr. Die Bedeutung der Kriegsgefangenenproblematik für die Geschichte des Kommunismus in Mittel- und Osteuropa 1917–1920, Wien/Köln/Weimar 2003

Rauchensteiner, Manfried: Der Erste Weltkrieg und das Ende der Habsburgermonarchie, Wien/Köln/Weimar 2013

Renolder, Thomas (Hrsg.): Animationsfilm in Österreich. Teil 1 1900–1970 (International Animated Film Association), Wien o.J.