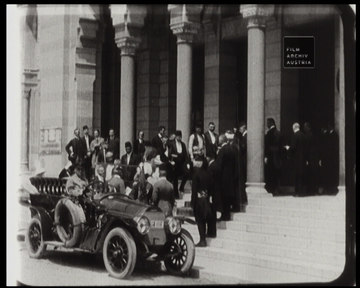

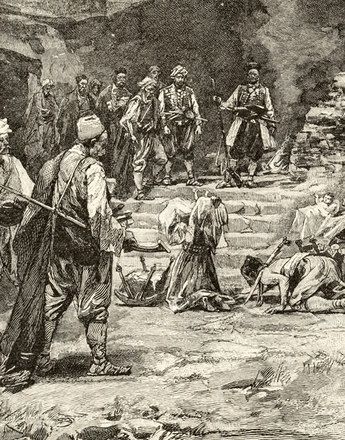

‘It's now or never!’ was the reaction to the news from Sarajevo that the successor to the Austrian-Hungarian throne and his wife had been assassinated. By July 1914 it was clear that a conflagration could not be avoided. The will to war and alliance-driven dynamics enjoyed greater favour than moderation and the willingness to compromise.

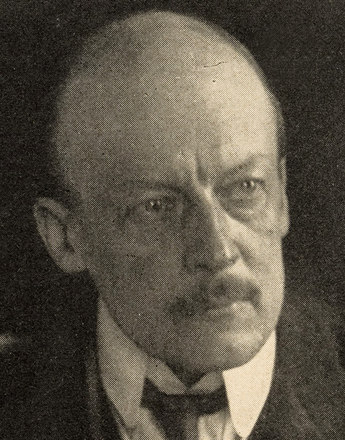

However, it was not seemingly inevitable mechanisms that proved inevitable, rather clearly identifiable actions carried out by key figures; actions that at closer examination were by no means uniform. So it seemed as though the German Imperial Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg supported for a while attempts at agreement with Britain, whilst in the Habsburg Empire the Hungarian Prime Minister, Stefan Count Tisza, initially advised against the Habsburg Empire taking up arms. The Austro-Hungarian Foreign Minister Leopold Berchtold and Emperor Franz Joseph first sounded out the Hohenzollern Empire, until eventually the Austrian diplomat Alexander Count Hoyos returned with the so-called ‘blank cheque’, i.e. Berlin’s support for the Danube Monarchy commencing hostilities against Serbia, the latter held responsible for the assassination of Franz Ferdinand.

The aim of this was a short punitive expedition, a short and local conflict, since especially Wilhelm II and those around him expected a reserved attitude on the part of the other Great Powers. However, this turned out to be a grave miscalculation. The Habsburg Army proved itself in no way adequately prepared to carry out a quick ‘penalty kick’ against Serbia. Added to this was the hesitant attitude of some of the decision-makers. The Habsburg Foreign Minister Berchtold wanted to send an ultimatum to Belgrade only after the departure from Russia of the visiting French President, so as to give the potentially hostile allies in Paris and St. Petersburg no opportunity for immediate consultation.

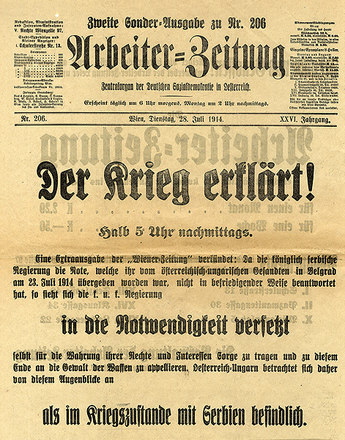

Once the Serbian government had replied in a most conciliatory tone to the conditions of the Habsburg Empire, it became clear that Vienna in particular had little interest in de-escalating the situation. The Sarajevo assassination, in which the heirs to the throne had been struck down by the young Bosnian Serb Gavrilo Princip, was certainly not the direct cause of the great catastrophe. It served more as a pretext, after almost a month, to launch the final strike. Within just a few days at the end of July and beginning of August 1914, this attitude led to the conflagration, the war that engulfed all the great powers of Europe.

Clark, Christopher: Die Schlafwandler. Wie Europa in den Ersten Weltkrieg zog, München 2013

Mombauer, Annika: Die Julikrise. Europas Weg in den Ersten Weltkrieg, München 2014

Moritz, Verena/Leidinger, Hannes: Die Nacht des Kirpitschnikow. Eine andere Geschichte des Ersten Weltkriegs, Wien 2006

Stevenson, David: The Outbreak of the First World War: 1914 in Perspective, New York 1997

Strachan, Hew: The Outbreak of the First World War, Oxford/New York 2004

-

Chapters

- The Fading-Out of the Balkan Front

- The War before the War

- Sarajevo and the July Crisis

- Ethnic Conflicts and the Brutalisation of the Battles

- Disillusionment for the Army – The Failed ‘Punitive Expedition’

- ‘The Allies’ Successes’

- The Occupying Regime in Different Regions

- Romania's Entry into the War and Defeat by the Central Powers

- Greece on the Side of the Entente

- 1918 – Peace between Romania and the Central Powers

- Consequences of the War on the Balkans