After losing their influence over the German countries and a majority of their possessions in Italy, the Habsburgs started to turn their attention towards the Balkans. In Viennese court and government circles, matters of prestige were of high importance. The ‘reputation of the Monarchy’ was primarily concerned with putting Serbia in its place. Almost obsessed with this goal, the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy was willing to ignore the international consequences of their actions and thereby ultimately threaten the peace of all of Europe.

An attempt made after the Russian war against the Ottoman Empire in 1877/8 to re-establish the balance of the Great Powers as an order of peace – as in 1814/15 – ultimately failed around 1900, after a few attempts at reconciliation. When in 1908 the Habsburg Empire incorporated Bosnia-Herzegovina, which it had occupied with the Berlin Congress of 1878 (though it had formally stayed part of the Ottoman Empire), the ‘Annexation Crisis’ developed, leading to a souring of relations between Vienna and St. Petersburg.

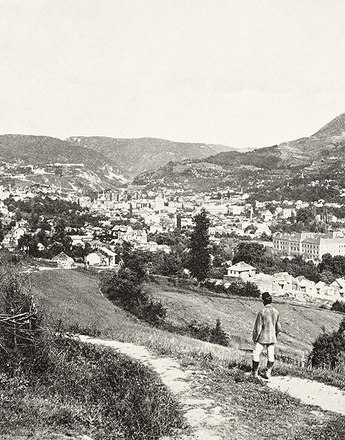

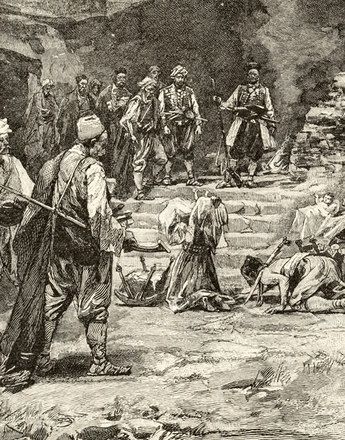

Against this background, the diplomacy of the leading European countries failed to ease the tension in any lasting way. On the contrary, it proved to be rather toothless, when in 1912/13 Bulgaria, Serbia, Greece and Montenegro started to invade the ‘sick man on the Bosphorus’, snatching up the remaining European territories of the Ottoman Empire and then fighting each other, including Romania and Turkey, over their ‘prey’.

The Serbian-Montenegrin territorial claims finally attracted the attention of the Danube Monarchy. Their troops in Bosnia-Herzegovina were reinforced. Parallel to this, Vienna aired a plan to found an independent Albania to counter the expansion of the neighbouring countries, especially towards the Adriatic. The subsequent rivalries led to an Austrian ultimatum, urging Belgrade in particular to withdraw its troops from Albanian territory.

Given the possibility of Russia supporting Serbia, a European war of this kind could no longer be ruled out, whereby the attitude that personal interests would, if necessary, be enforced by violence prevailed almost everywhere. Even pessimistically minded generals accordingly decided to risk all by the use of arms. Thus the political, diplomatic and military crisis, triggered at least in part by the situation in the Balkans, was intensified by prescribed mindsets.

Afflerbach, Holger: Der Dreibund. Europäische Großmacht- und Allianzpolitik vor dem Ersten Weltkrieg, Wien/Köln/Weimar 2002

Burkhardt, Johannes et al.: Lange und kurze Wege in den Ersten Weltkrieg, München 1996

Mombauer, Annika: The Origins of the First World War. Controversies and Consensus, London 2002

-

Chapters

- The Fading-Out of the Balkan Front

- The War before the War

- Sarajevo and the July Crisis

- Ethnic Conflicts and the Brutalisation of the Battles

- Disillusionment for the Army – The Failed ‘Punitive Expedition’

- ‘The Allies’ Successes’

- The Occupying Regime in Different Regions

- Romania's Entry into the War and Defeat by the Central Powers

- Greece on the Side of the Entente

- 1918 – Peace between Romania and the Central Powers

- Consequences of the War on the Balkans