‘Brothers in arms’: Austria-Hungary and Germany as partners and allies

-

“Shoulder to shoulder”, from the “War memories 1914-15” postcard album

Copyright: Schloß Schönbrunn Kultur- und Betriebsges.m.b.H.

Partner: Schloss Schönbrunn Kultur- und Betriebsges.m.b.H. -

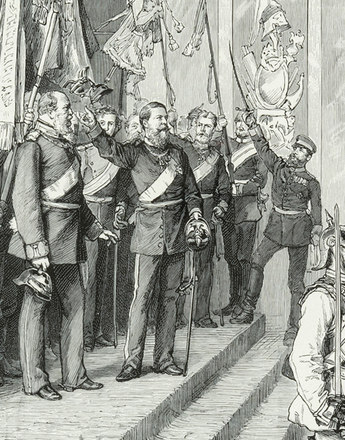

The Supreme Command of the German Army, photo 1916

Copyright: dform

-

Badge with the German, Austrian and Hungarian coats of arms

Copyright: Wien Museum

Partner: Wien Museum

The oft-invoked ‘brotherhood in arms’ between Vienna and Berlin was in reality an alliance between two very unequally matched ‘brothers’ who had differing aims and were sometimes even rivals.

Since being defeated by the Prussians at the battle of Königgrätz in 1866 the Austrian elites had entirely lost their self-confidence. In Bismarck’s plans for Germany as a great power the Habsburg Monarchy only had the role of a junior partner and the Austrians had not quite been able to come to terms with their loss of hegemony in the German-speaking world.

The rise of the unified German Empire from 1871 onwards had always been viewed with a certain ambivalence in Vienna. On the one hand there was a secret admiration for Prussian militarism and in many cases the Reich was used as a model for economic development. On the other hand, Austrian self-respect was eroded by having to admit to taking second place. This was also the cause of domestic political problems, as the strengthening radical wing of the German nationalist movement in the Habsburg Monarchy increasingly became oriented towards Berlin rather than Vienna.

Germany – a young nation-state that was still learning how to handle its newly acquired position as a political and economic great power – had little understanding of or sympathy for the complex structures and specific problems of the multi-national Habsburg Monarchy. To put it bluntly, the Prussians thought that Austria-Hungary was well past its sell-by date, a relic of the dynastic politics of bygone centuries. ‘Austria’ stood for weariness, decadence, sloppiness (‘Schlamperei’) and inconsistency.

This led to a number of misjudgements on both sides concerning the strengths and weaknesses of the respective other. While Vienna often overestimated Germany’s actual potential, Germany sometimes underestimated the strength of the old Habsburg Monarchy.

When in July 1914 all the signs were that war was in the offing, it became clear how divergent the ideas and aims of the two alliance partners were. Nor were there any concrete agreements regarding the war aims; and while the strategy of the Danube monarchy was focused on Serbia and the Balkans, Germany from the very beginning had its eye principally on the conflict with France.

There was also astonishingly little in the way of military-strategic cooperation between the two allies on the eve of the war, and what cooperation they did engage in was more suggestive of rivalry than of a ‘brotherhood in arms’. The respective military staffs took to operating in the strictest secrecy and allowed each other as little access as possible to their own strategic and logistic affairs. Only when the war began did it become necessary to play with open cards, as it would otherwise have been impossible to coordinate a common strategy.

This explains the surprise of the German Supreme Command at the teething problems Austria had with general mobilization in August 1914, when the Austrian General Staff announced that it would take fourteen days for the army to get ready for war, because most of the soldiers in the primarily agricultural state of Austria-Hungary were on furlough for the harvest. The Danube Monarchy was clearly not prepared for a war.

This was also evident as the war progressed, when the Austrian army and the administration in the hinterland experienced massive problems in the field of supplies and reinforcements. After having enjoyed little success in the initial phase of the war, the Austrian army became ever more dependent on assistance from the German forces.

As a result, the summer of 1916 saw the supreme command being taken over entirely by the Germans. Once Vienna had been compelled to give its agreement to a common high command, the Germans had the say over the Austrian generals. Although in public there was a highly emotive emphasis on ‘Nibelung loyalty’ between the two allies, off the record the Austrian Chief of General Staff Conrad von Hötzendorf referred to Germany as ‘our secret enemy’.

Translation: Peter John Nicholson

Bihl, Wolfdieter: Der Erste Weltkrieg 1914–1918. Chronik – Daten – Fakten, Wien/Köln/Weimar 2010

Hamann, Brigitte: Der Erste Weltkrieg. Wahrheit und Lüge in Bildern und Texten, 2. Aufl., München 2009

Hanisch, Ernst: Der lange Schatten des Staates. Österreichische Gesellschaftsgeschichte im 20. Jahrhundert [Österreichische Geschichte 1890–1990, hrsg. von Herwig Wolfram], Wien 2005

Hirschfeld, Gerhard/Krumeich, Gerd/Renz, Irina (Hrsg.): Enzyklopädie Erster Weltkrieg. Aktualisierte und erweiterte Studienausgabe, Paderborn/Wien [u.a.] 2009

Geiss, Imanuel: Deutschland und Österreich-Ungarn beim Kriegsausbruch 1914. Eine machthistorische Analyse, in: Gehler,Michael/Schmidt, Rainer F. (Hrsg): Ungleiche Partner? Österreich und Deutschland in ihrer gegenseitigen Wahrnehmung (Historische Mitteilungen der Rankegesellschaft Beiheft 15), Stuttgart 1996, 375–398

Leidinger Hannes/Moritz, Verena: Der Erste Weltkrieg, Wien [u.a.] 2011

Rauchensteiner, Manfried: Der Erste Weltkrieg und das Ende der Habsburgermonarchie 1914–1918, Wien u. a. 2013

-

Chapters

- The enthusiasm for the war

- ‘Brothers in arms’: Austria-Hungary and Germany as partners and allies

- Front lines – The course of the war 1914–16

- Italy enters the war

- The impact of the war on civilian society

- The accession of Emperor Karl

- The Sixtus Letters – Karl’s quest for a way out

- Karl’s bid for freedom

- The Russian Revolution and its consequences

- 1917 – The turning point