-

Assassination of Minister Presidemnt Graf Stürgkh, title page of the Illustrierten Kronenzeitung of 22 October 1916

Copyright: Universitätsbibliothek Wien

Partner: Universitätsbibliothek Wien -

Speech by Colonel General Franz Freiherr Conrad von Hötzendorf, head of the General Staff, sound recording, 1 November 1915

Copyright: Österreichische Mediathek

Partner: Österreichische Mediathek

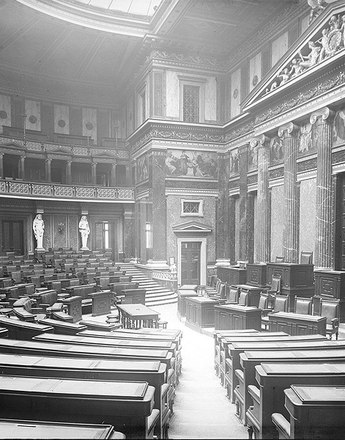

The Austrian parliament (‘Reichsrat’) had not been convened since March 1914. At the outbreak of the war its splendid home on the Ring was demonstratively transformed into a military hospital.

The body representing the people of the Austrian half of the Monarchy (‘Cisleithania’) had already been suspended a few months before the outbreak of war in July 1914 – and was to remain inactive until May 1917. The government operated with the constitution’s infamous emergency paragraph, which enabled it to carry through measures it considered necessary without reference to Parliament. This procedure had by that time become something of an Austrian tradition, having been used frequently before 1914.

This had to do with the specific political situation in Cisleithania, where parliamentarism was crippled by the conflict between the nationalities. As a result the Reichsrat had long since not functioned as a parliament but was, rather, a platform for the open display of nationalist chauvinism and radicalism.

Nevertheless, the suspension of the Reichsrat was an extreme measure that was not taken either in Hungary or in Germany, even though the representative bodies there were also increasingly forfeiting their role as monitors of government. In all three countries the military leadership was gaining increasing influence in the political sphere; furthermore, censorship and the general imperative to ‘all pull together’ resulted in the suppression of any criticism of the war policies.

The first months of the war saw the pressure rising in all fields of public life. The complete subordination of the civil administration to the needs of the army led to a state of affairs that Otto Bauer fittingly described as ‘bureaucratic war absolutism’. Under the direction of the army the civil service became the most important instrument of power, and one that was entirely beyond the control of any democratic body.

This dirigisme was particularly evident in trade and commerce, where all areas from production to distribution came under state supervision. The massive war measures were intended to effect a swift reorganization of an economy that had originally only been prepared for a war of short duration. Rationing was brought in to stabilize the failing food supply. As the war went on, the civil service was confronted with such an enormous catalogue of tasks that it could not possibly fulfil all the demands made upon it. Deficient coordination and a deluge of orders that could at best only be partially carried out soon made it clear to all that it was failing to perform its function.

The first year of the war saw the situation being aggravated by a number of painful military setbacks. The generals compensated for their failure with a more aggressive approach to problems at home. The militarization of society peaked with a call for the army to be entrusted with the administration of Bohemia and Croatia, where it was thought that there would be a greater propensity towards resistance. Finally this demand was not fully carried out.

Nevertheless, those areas of the Monarchy that were in the theatre of war were entirely subjected to army administration: in Galicia and the regions on the Italian border the civilian population was forcibly evacuated, with sectors of society considered ‘unreliable’ for reasons of nationalism or political orientation being brutally eliminated.

Measures became ever more draconian as the prospect of an end to the war receded. To all intents and purposes the demands of the army were aimed at the introduction of a military dictatorship.

It was with the country in this state of extreme tension that the news burst of the assassination of the Austrian Minister-President (Prime Minister) Count Karl Stürkgh on 21 October 1916. The very embodiment of the authoritarian military-bureaucratic regime that had been established in the Habsburg Monarchy, Stürkgh had obstinately refused to reconvene the Reichsrat. The man who killed him was a leading Social Democrat, Dr Friedrich Adler, who gave as grounds for his deed the necessity of drawing attention to the impossible state of affairs that had been reached.

Translation: Peter John Nicholson

Bihl, Wolfdieter: Der Erste Weltkrieg 1914–1918. Chronik – Daten – Fakten, Wien/Köln/Weimar 2010

Hamann, Brigitte: Der Erste Weltkrieg. Wahrheit und Lüge in Bildern und Texten, 2. Aufl., München 2009

Hanisch, Ernst: Der lange Schatten des Staates. Österreichische Gesellschaftsgeschichte im 20. Jahrhundert [Österreichische Geschichte 1890–1990, hrsg. von Herwig Wolfram], Wien 2005

Hirschfeld, Gerhard/Krumeich, Gerd/Renz, Irina (Hrsg.): Enzyklopädie Erster Weltkrieg. Aktualisierte und erweiterte Studienausgabe, Paderborn/Wien [u.a.] 2009

Leidinger Hannes/Moritz, Verena: Der Erste Weltkrieg, Wien [u.a.] 2011

Rauchensteiner, Manfried: Der Erste Weltkrieg und das Ende der Habsburgermonarchie 1914–1918, Wien u. a. 2013

-

Chapters

- The enthusiasm for the war

- ‘Brothers in arms’: Austria-Hungary and Germany as partners and allies

- Front lines – The course of the war 1914–16

- Italy enters the war

- The impact of the war on civilian society

- The accession of Emperor Karl

- The Sixtus Letters – Karl’s quest for a way out

- Karl’s bid for freedom

- The Russian Revolution and its consequences

- 1917 – The turning point