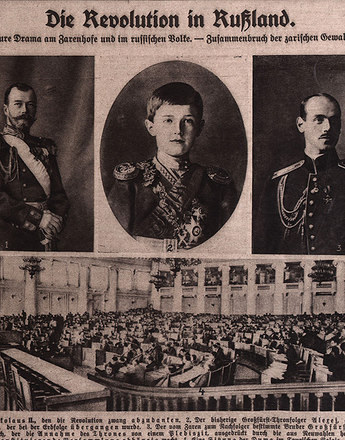

The situation in Russia at the beginning of 1917 was catastrophic. The food supply system had broken down and the populace in the large towns and cities was starving and freezing. The voices calling for a completely new ordering of society became ever louder. The autocratic rule of the Tsar was nearing its end.

The general discontent was expressed in the mass demonstrations of February 1917. When Tsar Nicholas II gave orders that the unrest should be brought to an end with all available means, the soldiers mutinied and refused to obey their firing orders, which led to the rapid fall of Tsarist rule. Contrary to the hopes of many Russians, the seizure of power by the constitutional middle-class parties under Prime Minister Alexander Kerensky did not bring changes in Russia’s alliance commitments. On the contrary, Russia remained at war, in spite of the general exhaustion and clear signs that the army was falling apart.

The bourgeois government found itself faced by increasing pressure from the workers’ and peasants’ councils (‘Soviets’). In order to destabilize the situation still further, the German military command notoriously had the leader of the radical Bolshevik party, Vladimir I. Lenin, returned to Russia from exile. Finally, Kerensky’s increasingly dictatorial regime was overthrown at the Bolshevik revolution of November 1917 (known as the ‘October Revolution’ on account of the different calendar used by the Orthodox).

However, the attempt to satisfy the general call for peace and national self-determination led to chaos and subsequently to a civil war.

The collapse of the Russian army, which finally capitulated on 17 December 1917, was an event of enormous importance for the course of the war. It brought the Central Powers huge territorial gains, as the Ukraine, the Baltic region and parts of the Caucasus were by now under the control of the German army.

For Germany, the peace of Brest-Litovsk concluded by Russia and the Central Powers in March 1918 meant that it was no longer fighting a war on two fronts. While peace was a necessity for the Bolshevik regime if it was to be able to consolidate its hold on power, the conditions dictated by Berlin were extremely severe. In addition to enormous reparation payments, Russia had to give up Poland and accept the secession of the Baltic, the Ukraine and Finland. Further areas of Russia occupied by the Central Powers were to remain under German control until the end of the war.

At first sight this meant a new high point in Germany’s territorial expansion. However, the ‘dictated peace of the German imperialists’ also provided the Bolsheviks with an ideal screen on which to project their uncompromising desire for peace. In spite of the high costs imposed on Russia, the peace of Brest-Litovsk was a great propaganda success that gave new life to revolutionary forces in a war-weary Europe. The Russian revolution became a threatening example of what failure on the part of the elites could lead to. Emperor Karl also became aware of what might happen to Austria-Hungary if he continued the policies that had been followed until then.

Translation: Peter John Nicholson

Bihl, Wolfdieter: Der Erste Weltkrieg 1914–1918. Chronik – Daten – Fakten, Wien/Köln/Weimar 2010

Hildermeier, Manfred: Die Russische Revolution 1905–1920 (4. Auflage), Frankfurt 1995

Hirschfeld, Gerhard/Krumeich, Gerd/Renz, Irina (Hrsg.): Enzyklopädie Erster Weltkrieg. Aktualisierte und erweiterte Studienausgabe, Paderborn/Wien [u.a.] 2009

Leidinger Hannes/Moritz, Verena: Der Erste Weltkrieg, Wien [u.a.] 2011

Rauchensteiner, Manfried: Der Erste Weltkrieg und das Ende der Habsburgermonarchie 1914–1918, Wien u. a. 2013

-

Chapters

- The enthusiasm for the war

- ‘Brothers in arms’: Austria-Hungary and Germany as partners and allies

- Front lines – The course of the war 1914–16

- Italy enters the war

- The impact of the war on civilian society

- The accession of Emperor Karl

- The Sixtus Letters – Karl’s quest for a way out

- Karl’s bid for freedom

- The Russian Revolution and its consequences

- 1917 – The turning point