Women! Don’t write gloomy letters!

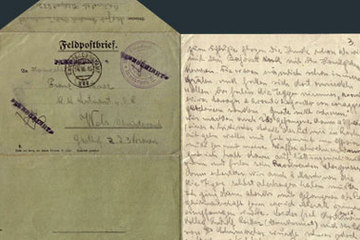

The daily newspapers in Austria and Hungary published frequent appeals urging women to send only cheerful and edifying letters to their relatives at the front.

As recommended by the authorities, the model letter sent to the front should demonstrate calm endurance and the courageous bearing of the various burdens and travails resulting from the war. There should be no place in these letters for personal fears, worries or even criticism of the prevailing conditions.

In Germany for example Malita von Rundstedt propagated the following guidelines for women in her treatise Der Schützengraben der Frau (The German Woman’s Trench) published in 1916: ‘Yes, letters from home constitute a great power at the front, and this [power] is put into our womanly hands. A letter can easily make a man a hero or a coward, can help him to earn the Iron Cross, but also tempt him into abandoning his soldier’s honour […]. Therefore I would urge you, women of Germany, always to write only letters of a sunny nature to the front.’

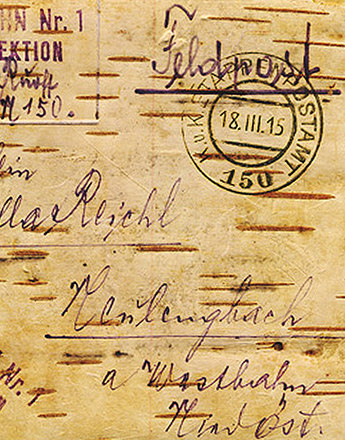

If women disregarded these guidelines, their letters were frequently returned by the Imperial and Royal Censor’s Office, together with the appropriate admonition.

None other than Adolf Hitler in Mein Kampf later censured women for repeatedly rejecting the role demanded of them as correspondents courageously bearing their adversity in silence. As the historian Christa Hämmerle has pointed out, he accused the women of the time with the ‘moaning and wailing’ in their letters of bearing major responsibility for the undermining of morale among soldiers at the front and thus also of negatively influencing the outcome of the war. Hämmerle also states that the so-called Dolchstoßlegende (‘stab-in-the-back myth’) therefore also assumes ‘an explicitly gender-political dimension’.

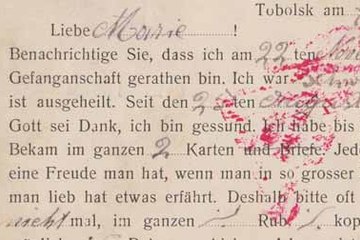

The responsible military and political authorities recognized that the letters written by women and men were mutually dependent and had a reciprocal influence on one another. This is an aspect that has long been neglected by researchers in the field, who have tended to concentrate on soldiers’ letters and the ‘male experience of war’ that they reflect. This has changed only recently, above all in research focusing on the history of women and gender. On the one hand this research has critically re-examined wartime society, which was organized in keeping with traditional gender attribution. On the other hand it has enabled scholars to elaborate the letter-writers’ multifarious images of ‘Self’ and the ‘Other’, which were closely bound up with contemporaneous definitions of ‘male’ and ‘female’ roles. In their wartime correspondence, many male letter-writers for example sought to maintain their role as family bread-winner and father. Conversely, as the war progressed, in their letters to their husbands, fathers, brothers or sons, many women assumed a new active role in the mutual exchange of ideas about politics by relating and often critically reflecting upon what they read every day as well as the political, social and economic debates that were being conducted on the home front.

Translation: Sophie Kidd

Hämmerle, Christa: Entzweite Beziehungen? Zur Feldpost der beiden Weltkriege aus frauen- und geschlechtergeschichtlicher Perspektive, in: Veit Didczuneit/Jens Ebert/Thomas Jander (Hrsg.): Schreiben im Krieg. Schreiben vom Krieg. Feldpost im Zeitalter der Weltkriege, Essen 2011, 241-252

Hämmerle, Christa: „… wirf Ihnen alles hin und schau, dass Du fortkommst.“ Die Feldpost eines Paares in der Geschlechter(un)ordnung des Ersten Weltkriegs, in: Historische Anthropologie (1998), 6/3, 431-458

Rebhan-Glück, Ines: „Wenn wir nur glücklich wieder beisammen wären …“ Der Krieg, der Frieden und die Liebe am Beispiel der Feldpostkorrespondenz von Mathilde und Ottokar Hanzel (1917/18), Unveröffentlichte Diplomarbeit, Wien 2010

Rebhan-Glück, Ines: Liebe in Zeiten des Krieges. Die Feldpostkorrespondenz eines Wiener Ehepaares (1917/18), in: ÖGL (2012), 56/3, 231–246

Spann, Gustav: Vom Leben im Kriege. Die Erkundung der Lebensverhältnisse der Bevölkerung Ungarns im Ersten Weltkrieg durch die Briefzensur, in: Ardelt, Rudolf G./Huber, Wolfgang J.A. (Hrsg.): Unterdrückung und Emanzipation. Festschrift für Erika Weinzierl zum 60. Geburtstag, Wien 1985, 149-165

Tramitz, Angelika: Vom Umgang mit Helden. Kriegs(vor)schriften und Benimmregeln für deutsche Frauen im Ersten Weltkrieg, in: Knoch, Peter (Hrsg.): Kriegsalltag: die Rekonstruktion des Kriegsalltags als Aufgabe der historischen Forschung und der Friedenserziehung, Stuttgart 1989, 84-113

Quotes:

„Yes, letters from home ...“: Malita von Rundstedt, Der Schützengraben der Deutschen Frau, quoted from: Tramitz, Angelika: Vom Umgang mit Helden. Kriegs(vor)schriften und Benimmregeln für deutsche Frauen im Ersten Weltkrieg, in: Knoch, Peter (Hrsg.): Kriegsalltag: die Rekonstruktion des Kriegsalltags als Aufgabe der historischen Forschung und der Friedenserziehung, Stuttgart 1989, 97 (Translation: Sophie Kidd)

„If women disregarded these guidelines …“: Spann, Gustav: Vom Leben im Kriege. Die Erkundung der Lebensverhältnisse der Bevölkerung Ungarns im Ersten Weltkrieg durch die Briefzensur, in: Ardelt, Rudolf G./Huber, Wolfgang J.A. (Hrsg.): Unterdrückung und Emanzipation. Festschrift für Erika Weinzierl zum 60. Geburtstag, Wien 1985, 153

„[…] he accused the women of the time ...“: Hämmerle, Christa: Entzweite Beziehungen? Zur Feldpost der beiden Weltkriege aus frauen- und geschlechtergeschichtlicher Perspektive, in: Veit Didczuneit/Jens Ebert/Thomas Jander (Hrsg.): Schreiben im Krieg. Schreiben vom Krieg. Feldpost im Zeitalter der Weltkriege, Essen 2011, 245

„an explicitly gender-political dimension ...“: Hämmerle, Christa: Entzweite Beziehungen? Zur Feldpost der beiden Weltkriege aus frauen- und geschlechtergeschichtlicher Perspektive, in: Veit Didczuneit/Jens Ebert/Thomas Jander (Hrsg.): Schreiben im Krieg. Schreiben vom Krieg. Feldpost im Zeitalter der Weltkriege, Essen 2011, 245

-

Chapters

- Feldpost as an instrument of warfare

- How did a letter get from A to B?

- The dialogue between the front line and the home front

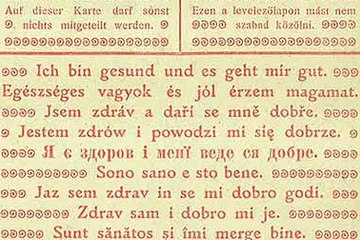

- ‘I am healthy and doing well.’

- The sending of ‘gifts of love’ to the front line and food parcels to the home front

- Instrumentalizing war correspondence to shape common perceptions of the war

- Women! Don’t write gloomy letters!