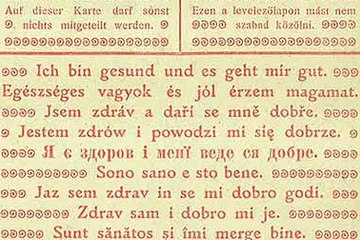

‘I am healthy and doing well.’

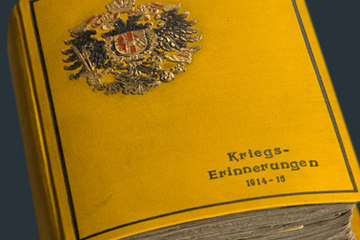

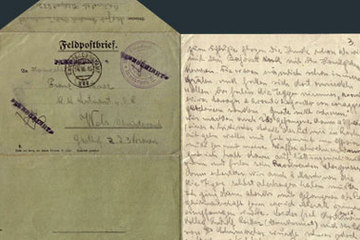

During the First World War correspondence between the front line and the home front became a mass cultural phenomenon encompassing all levels of society.

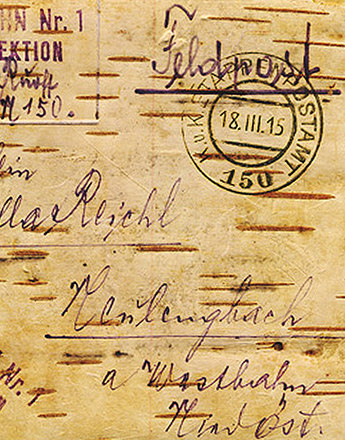

Accordingly, the military authorities went to great lengths to ensure that postal traffic functioned as smoothly as possible. In view of the huge volumes of mail and – especially at the beginning of the war – the frequent troop movements, this was only partially successful. Delays, wrong delivery and losses were common, in part due to items being incorrectly addressed. The problems that the military postal service encountered very soon provoked the first complaints from soldiers and their relatives. This predicament was made worse by the repeated interruption of postal traffic by so-called Postsperren (postal embargo/suspension of postal services). These were decreed for a variety of reasons, including the concealment of troop redeployments and offensives, but also because of the often rapid rise in the numbers of letters and parcels within a short space of time. The volume of items sent, especially at Christmas, quite simply exceeded the capacity of the Imperial and Royal Feldpost to convey them.

In order to alleviate anxiety and complaints among soldiers at the front and those at home, from 28 August 1916 special field service postcards on pre-printed green paper were issued in Austria-Hungary bearing the message Ich bin gesund und es geht mir gut (‘I am healthy and doing well’) in the nine languages of the multi-ethnic Habsburg Empire: German, Hungarian, Czech, Polish, Ruthenian, Italian, Slovenian, Serbo-Croat and Romanian. Sent in their millions, these postcards were not allowed to bear any additional information but could be used as a substitute for banned private communications during a postal embargo.

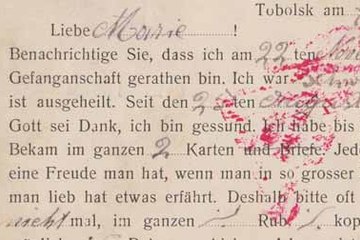

However, the issuing of these pre-printed postcards failed to stem the complaints expressed in many letters about the non-appearance of mail or lengthy delivery times. Typical examples of this can be found in the wartime correspondence of the middle-class couple Mathilde and Ottokar Hanzel, where the former writes in December 1917: ‘Owing to the appalling conditions currently prevailing in the postal system no green postcard has arrived.’ Or a month later, in January 1918: ‘I am very sorry that the post is so wretchedly slow […].’

Translation: Sophie Kidd

Clement, Alfred (Hrsg.): Handbuch der Feld- und Militärpost II. 1914-1918, Graz 1964

Hämmerle, Christa: „… wirf Ihnen alles hin und schau, dass Du fortkommst.“ Die Feldpost eines Paares in der Geschlechter(un)ordnung des Ersten Weltkriegs, in: Historische Anthropologie (1998), 6/3, 431–458

Rebhan-Glück, Ines: Liebe in Zeiten des Krieges. Die Feldpostkorrespondenz eines Wiener Ehepaares (1917/18), in: ÖGL (2012), 56/3, 231–246

Ulrich, Bernd: Die Augenzeugen. Deutsche Feldpostbriefe in Kriegs- und Nachkriegszeit 1914-1933, Essen 1997

Quotes:

„Owing to the appalling conditions ...“: Mathilde Hanzel to Ottokar Hanzel, 23.12.1917, Sammlung Frauennachlässe, Nachlass 1, Institut für Geschichte der Universität Wien (Translation: Sophie Kidd)

„I am very sorry ...“: Mathilde Hanzel to Ottokar Hanzel, 08.01.1918, Sammlung Frauennachlässe, Nachlass 1, Institut für Geschichte der Universität Wien (Translation: Sophie Kidd)

-

Chapters

- Feldpost as an instrument of warfare

- How did a letter get from A to B?

- The dialogue between the front line and the home front

- ‘I am healthy and doing well.’

- The sending of ‘gifts of love’ to the front line and food parcels to the home front

- Instrumentalizing war correspondence to shape common perceptions of the war

- Women! Don’t write gloomy letters!