Feldpost as an instrument of warfare

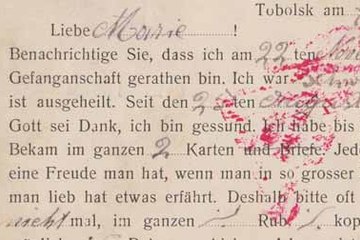

In the age of universal conscription and the modern mass army the existence of a military postal service came to have a special importance. The increasing totalization of warfare demanded a high degree of social control and the wholesale psychological mobilization of the belligerent nations. Private correspondence was intended to bolster and support the mental health of troops at the front confronted with ‘modern’ industrialized warfare.

The importance of a field postal service in this respect can be seen not only in soldiers’ letters and journals but also in military reports and accounts. Army high command had already recognized this during the course of the nineteenth century; the Prussian field marshal general and general chief of staff Count Helmuth von Moltke, is reported as saying: ‘War cannot be fought without a military postal service’.

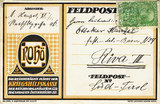

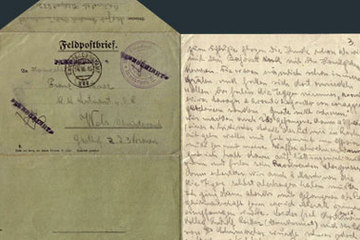

In 1913 the structure, organization and scope of activity of the military postal system was reorganized in Austria-Hungary as set out in the Dienstbuch E-47. According to this rulebook, the Imperial and Royal Feldpost was a ‘joint army institution’, the task of which was to convey all official and private post (‘letters, postcards, printed material, newspapers, commercial samples and parcels’) between the army in the field and the home front.

When the Imperial and Royal Feldpost began its work immediately after war was declared (in early August), 118 field post offices were set up and staffed by 620 officials. By the end of the First World War and the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Feldpost the number of field post offices had risen to 500 and that of the base post offices to 200. At the end of 1918 around 2,800 officials were employed in the Austro-Hungarian military postal service.

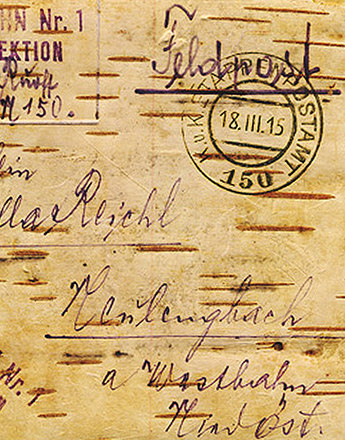

All Austro-Hungarian main, field and base post offices had a number that was assigned at random. This ensured that the location and movements of individual troop units were kept secret and also made it easier to sort the huge volumes of mail. The numbers contained the essential address coordinates to ensure accurate and expeditious delivery of letters, postcards and parcels to the fronts. The address of a soldier was composed of their rank, first and family names, the body of troops they were attached to and the number of the relevant field post office.

In February 1917 this system of field post office numbers was also adopted in the German Empire, where they had previously been designated according to troop headquarters and high command headquarters.

From the beginning of the war items sent via the Austro-Hungarian military postal system were subject to censorship operating in all the languages of the Monarchy. However, in view of the huge volumes of mail, the total censorship that had initially prevailed had to be abandoned during the course of 1914. From 1915 post was only checked at random.

Translation: Sophie Kidd

Clement, Alfred (Hrsg.): Handbuch der Feld- und Militärpost II. 1914-1918, Graz 1964

Hämmerle, Christa: „… wirf Ihnen alles hin und schau, dass Du fortkommst.“ Die Feldpost eines Paares in der Geschlechter(un)ordnung des Ersten Weltkriegs, in: Historische Anthropologie (1998), 6/3, 431-458

Höger, Paul: Das Post- und Telegraphenwesen im Weltkrieg, in: Gatterer, Joachim/Lukan, Walter (Red.): Studien und Dokumente zur österreichisch-ungarischen Feldpost im Ersten Weltkrieg, Bd. 1, Wien 1989, 23-54

Humburg, Martin: Das Gesicht des Krieges. Feldpostbriefe von Wehrmachtssoldaten aus der Sowjetunion 1941-1944, Wiesbaden 1998

Rebhan-Glück, Ines: „Wenn wir nur glücklich wieder beisammen wären …“ Der Krieg, der Frieden und die Liebe am Beispiel der Feldpostkorrespondenz von Mathilde und Ottokar Hanzel (1917/18), Unveröffentlichte Diplomarbeit, Wien 2010

Spann, Gustav: Zensur in Österreich während des Ersten Weltkrieges 1914-1918, Unveröffentlichte Dissertation, Universität Wien 1972

Quotes:

„War cannot be fought ...“: von Moltke, Helmut, quoted from: Höger, Paul: Das Post- und Telegraphenwesen im Weltkrieg, in: Gatterer, Joachim/Lukan, Walter (Red.): Studien und Dokumente zur österreichisch-ungarischen Feldpost im Ersten Weltkrieg, Bd. 1, Wien 1989, 40

„joint army institution“: quoted from: Clement, Alfred (Hrsg.): Handbuch der Feld- und Militärpost II. 1914-1918, Graz 1964, 336

„letters, postcards, printed material, ...“: quoted from: Clement, Alfred (Hrsg.): Handbuch der Feld- und Militärpost II. 1914-1918, Graz 1964, 337

„When the Imperial and Royal Feldpost ...“: figures, quoted from: Clement, Alfred (Hrsg.): Handbuch der Feld- und Militärpost II. 1914-1918, Graz 1964, 334

„This ensured that the location …“: Clement, Alfred (Hrsg.): Handbuch der Feld- und Militärpost II. 1914-1918, Graz 1964, 344

„In February 1917 this system …“: Clement, Alfred (Hrsg.): Handbuch der Feld- und Militärpost II. 1914-1918, Graz 1964, 399

-

Chapters

- Feldpost as an instrument of warfare

- How did a letter get from A to B?

- The dialogue between the front line and the home front

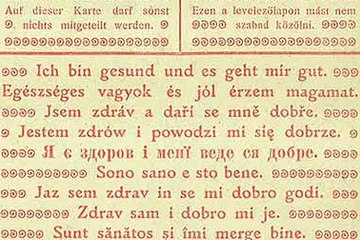

- ‘I am healthy and doing well.’

- The sending of ‘gifts of love’ to the front line and food parcels to the home front

- Instrumentalizing war correspondence to shape common perceptions of the war

- Women! Don’t write gloomy letters!