Significant profits were accrued from the war industry in Vienna, prompting the government in 1916 to introduce a staggered war profit tax. This measure increased wage costs and inflation and caused a drop in profits in the last year of the war, considerably dampening industrialists’ enthusiasm for the war.

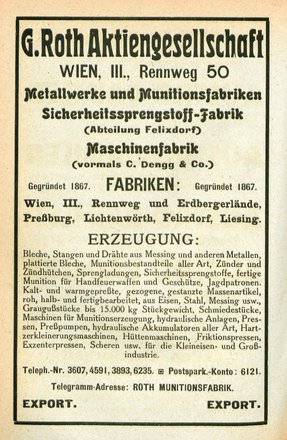

In spite of the economic swings and the collapse of production towards the end of the war, there were clear economic winners and losers among Viennese businesses. Among the largest military suppliers, which by the end of 1917 had received orders worth over 100 million krone, were not only companies with head offices in Vienna but also ones with factories in the city. Pulverfabrik G. Roth AG registered orders worth 379 million krone, AG Dynamit Nobel 145 million, C.T. Petzold & Co., ammunition and barracks manufacturers, 145 million, and Vereinigte Jutefabriken 138 million. The largest volume of business, however, was done by the food wholesaler and canning factory B. Wetzler & Co. It received orders worth 1.2 billion krone (equivalent to 290 million “peacetime krone”), more by far even than the Škoda works in Pilsen [Plzeň], for example. For a time – and in some cases almost until the end of the war – companies in the textile and leather industries, arms and ammunition manufacturers, and the mechanical, locomotive, automobile and chemical industries made huge profits. By contrast, the paper and construction industries, banks and transport companies fared badly.

Arms manufacturers like G. Roth AG did particularly well. Its net profit in 1916 and 1917 was three times that of Siemens-Schuckert-Werke and Wiener Lokomotiv-Fabriks-AG in Floridsdorf. Some major electrical engineering companies had only nominal improvements in net profits between 1913 and 1917. Converted into gold krone, few showed a real increase in profits, although Österreichische Brown-Boveri-Werke in the 10th district was extremely successful.

The profits by some sectors prompted the introduction in 1916 of a war profit tax. It was staggered from 5 to 45 per cent as a function of pre-war revenues by companies and additional income by private individuals between 1914 and 1916, with 1 January 1913 to 31 July 1914 as the baseline. By the end of 1919 this war profit tax was the most successful direct tax in Austria, amassing 1.8 billion krone. Its introduction, increased labour costs and devaluation ultimately meant that net profits in the war industry started to shrink discernibly from 1917 onwards. The heyday of the armaments industry had passed. Moreover, in the last year of the war the government cut back orders by the military to the armaments industry and sought more stringent budgeting in order to reduce the demand for financial resources. In view of the dwindling profit margin, the “patriotic” enthusiasm of industrialists also waned, and some companies began to restructure even while the war was still being waged.

Translation: Nick Somers

Grandner, Margarete: Kooperative Gewerkschaftspolitik in der Kriegswirtschaft. Die freien Gewerkschaften Österreichs im ersten Weltkrieg (Veröffentlichungen der Kommission für neuere Geschichte Österreichs 82), Wien/Köln/Weimar 1992

Grandner, Margarete: Hungerstreiks, Rebellion, Revolutionsbereitschaft, in: Pfoser, Alfred/Weigl, Andreas (Hrsg.): Im Epizentrum des Zusammenbruchs. Wien im Ersten Weltkrieg, Wien 2013, 558–565

Winkler, Wilhelm: Die Einkommensverschiebungen in Österreich während des Weltkrieges, Wien/New Haven 1930