The mobilisation crisis of the first months of the war

The first months of the war were characterised by a marked increase in unemployment in Vienna. Small businesses in particular, even in important sectors like metalworking, suffered from a drop in consumer demand before the transition to a war economy had been completed.

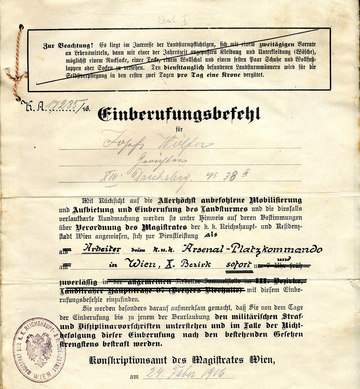

The Kriegsleistungsgesetz [War Powers Act] promulgated during the second Balkan war in 1912 and entering into force on 26 July 1914 permitted the direct and rapid militarisation of strategic production sectors. On this basis nearly all fit male civilians up to the age of fifty were recruited and obliged to work in the production of strategic goods. On 18 March 1917 women were also made subject to the War Powers Act. As soon as the first troop transports started heading for the Serbian and Russian fronts, the war began to make demands on economic resources in a way that had not been seen in any conflict hitherto. The consequences of this concerting of forces were thus felt on the Vienna labour market as early as the first weeks of August 1914. As the army commanders took little account of the strategic importance of skilled workers and also widely requisitioned means of transport, the first weeks of the war saw a high level of unemployment. By the end of August 1914, the number of unemployed is estimated to have risen to 150,000. Small businesses of no relevance to the war effort were particularly affected. Even the metalworking industry was hit. In the first three weeks of August, 566 Viennese businesses ceased production. Of 85,000 metalworkers, between 12,000 and 13,000 became unemployed.

While this structural unemployment following the transition of the Viennese production sector to a war economy quickly resolved itself, the problems caused by mass mobilisation persisted. By the end of 1914 the Austrian half of the empire had lost 25 per cent of its labour pool, while women were yet to make a significant addition to it. Companies in Vienna were also badly hit, as the trade inspectors noted in their reports. One of these reports including the industrial district of Floridsdorf stated: “With the start of mobilisation, a large number of subordinate workers but also the majority of the most skilled workers and a high proportion of management personnel left their jobs to join the military.” Individual examples also illustrate the general shortage of manpower: of the 5,500 employees of the Siemens-Schuckert-Werke in Vienna, a quarter had been conscripted by the end of 1914, and 6,000 of the 12,700 employees of the Vienna public transport system had joined the army. In many cases, those left behind didn’t have the necessary qualifications or physical constitution to maintain the level of productivity. The implementation of the Hindenburg programme at the end of 1916 also had an adverse affect, as it called for concentration on the armaments industry rather than investing in transport, leading to an even greater shortage of raw materials. As the war continued, undernourishment and the shortage of raw materials gradually brought the armaments industry to its knees. When ever younger recruits were conscripted at the beginning of 1918, the labour shortage effectively led to economic collapse in autumn 1918.

Translation: Nick Somers

Augeneder, Sigrid: Arbeiterinnen im Ersten Weltkrieg. Lebens- und Arbeitsbedingungen proletarischer Frauen in Österreich (Materialien zur Arbeiterbewegung 46), Wien 1987

Bericht der k. k. Gewerbe-Inspektoren über ihre Amtstätigkeit im Jahre 1914, Wien 1915

Egger, Rainer: Heeresverwaltung und Rüstungsindustrie, in: Baltzarek, Franz/Brauneder, Wilhelm (Hrsg.): Modell einer neuen Wirtschaftsordnung. Wirtschaftsverwaltung in Österreich 1914–1918, Frankfurt/M. et al. 1991, 81–104

N.ö. Handels- und Gewerbekammer in Wien: Bericht über die Industrie, den Handel und die Verkehrsverhältnisse in Niederösterreich während der Jahre 1914–1918, Wien 1920

Wegs, Robert J.: Die österreichische Kriegswirtschaft 1914–1918, Wien 1979