The exultation that erupted – most of all gripping the intellectual and academic classes and also the middle-class milieu –was rapidly overshadowed by the reality of the mechanised war. As the first statistics of losses were announced even the frenetic, jubilant shouts of many volunteers marching off to war faded into a sad echo.

By mid-September 1914, the Austrian-Hungarian Army had already marked up 400,000 losses (killed, wounded, taken prisoner). Newspapers reported the rates of loss and published long lists to enable the bereaved to identify fallen and wounded soldiers. Although the press endeavoured to euphemise the mood of the civil population, the gloom rapidly increased. The Nobel Peace Prize winner Alfred Hermann Fried noted on 28 September 1914 in his diary: "The mood in Vienna is low-spirited at the development of events. But it is patriotic to hide this from others. In the circle of my journalist friends someone said yesterday that now is the time to tell deliberate lies, in other words to present the mood as positive and strong."

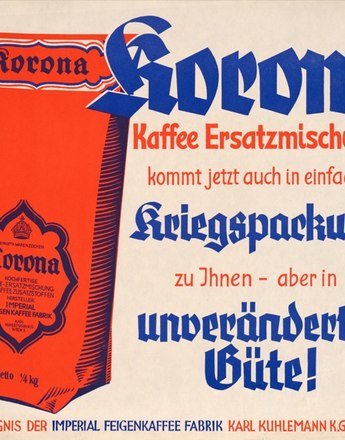

Not only the grief at losing family members, also the anxiety about their own existence had a negative effect on the civil population’s mood. It did not take long after the outbreak of war for food prices to shoot high and supplies to falter. Economic production was focused entirely on the armed forces; provisioning the troops had priority. Already by October 1914, Vienna did not have sufficient grain. There were drastic shortages in other major cities as well, which escalated more and more as the war progressed.

A report from the Police Directorate written on 15 April 1915 states: "The people’s mood is generally calm, patriotic and distinctly more positive again after the success of our troops in the Carpathians. But enthusiasm for the war has vanished, an indifference to the events of the war is becoming noticeable especially in the underclasses because of the distress that now holds sway. Everybody is longing for a prompt and peaceful conclusion."

Instead of the hoped-for peace, living conditions noticeably deteriorated. State measures to fight hunger and distress remained unsuccessful. Provision of food became increasingly difficult, food became scarcer and scarcer. Even rural areas were affected by the crisis in supplies and nutrition.

Military absolutism, censorship, militarisation of the economy and the food crisis caused the initial war craze to evaporate. Into its place stepped economic and military exhaustion, which flipped over into a revolutionary mood. The dearth gave rise already in 1916 to the first hunger riots and protests, their main participants were women and young people.

This was the start of a series of civil disturbances and mass strikes which was to escalate more and more until the end of the war. The civil population’s growing readiness to strike is a distinct sign of their increasing war fatigue and disillusionment. Because of the constantly deteriorating supply situation, numerous workers downed tools in May 1917 and also at the beginning and in the middle of the last year of the war. The people’s patience and endurance were at an end. In January 1918 a total of 700,000 workers went on strike in the Dual Monarchy. In June of the same year the protests came to a new peak. Because of a further reduction in bread and flour rations 50,000 of the employed in Vienna alone went on strike.

Translation: Abigail Prohaska

Pfoser, Alfred: Wohin der Krieg führt. Eine Chronologie des Zusammenbruchs, in: Pfoser, Alfred/Weigl, Andreas (Hrsg.): Im Epizentrum des Zusammenbruchs. Wien im Ersten Weltkrieg, Wien 2013, 578-687

Pfoser, Alfred/Weigl, Andreas: Die Pflicht zu sterben und das Recht zu leben. Der Erste Weltkrieg als bleibendes Trauma in der Geschichte Wiens, in: Dies. (Hrsg.): Im Epizentrum des Zusammenbruchs. Wien im Ersten Weltkrieg, Wien 2013, 14-31

Rauchensteiner, Manfried: Der Erste Weltkrieg und das Ende der Habsburgermonarchie 1914–1918, Wien/Köln/Weimar 2013

Winkelhofer, Martina: So erlebten wir den Ersten Weltkrieg. Familienschicksale 1914-1918. Eine illustrierte Geschichte, 2. Auflage, Wien 2013

Maderthaner, Wolfgang: „…Die Welt ist in die Hände der Menschen gefallen“ Anmerkungen zu einem zentralen Trauma der Moderne, in: Maderthaner, Wolfgang/Hochedlinger, Michael: Untergang einer Welt. Der große Krieg 1914–1918 in Photographien und Texten. Eine Publikation des Österreichischen Staatsarchivs, Wien 2013

Leidinger, Hannes/Moritz, Verena: Der Erste Weltkrieg, Wien/Köln/Weimar 2011

Hamann, Brigitte: Der Erste Weltkrieg. Wahrheit und Lüge in Bildern und Texten, München/Zürich 2004

Heiss, Hans: Andere Fronten, Volksstimmung und Volkserfahrung in Tirol während des Ersten Weltkrieges, in: Eisterer, Klaus/Steininger, Rolf (Hrsg.): Tirol und der Erste Weltkrieg, Innsbruck 2011, 139-177

Überegger, Oswald: Der andere Krieg. Die Tiroler Militärgerichtsbarkeit im Ersten Weltkrieg, Innsbruck 2002

Sauermann, Eberhard: Literarische Kriegsfürsorge. Österreichische Dichter und Publizisten im Ersten Weltkrieg, Wien/Köln/Weimar, 2000

Quotes:

"But enthusiasm for the war …": Stimmungsbericht der Polizeidirektion Wien, 15. April 1915, quoted from : Pfoser, Alfred: Wohin der Krieg führt. Eine Chronologie des Zusammenbruchs, in: Pfoser, Alfred/Weigl, Andreas (Hrsg.): Im Epizentrum des Zusammenbruchs. Wien im Ersten Weltkrieg, Wien 2013, 606 (Translation)

"The mood in Vienna …": Fried, Alfred H, quoted from: Pfoser, Alfred: Wohin der Krieg führt. Eine Chronologie des Zusammenbruchs, in: Pfoser, Alfred/Weigl, Andreas (Hrsg.): Im Epizentrum des Zusammenbruchs. Wien im Ersten Weltkrieg, Wien 2013, 578-687, 595 (Translation)

"The people’s mood …“: Stimmungsbericht der Polizeidirektion Wien, 15. April 1915, quoted from: Pfoser, Alfred: Wohin der Krieg führt. Eine Chronologie des Zusammenbruchs, in: Pfoser, Alfred/Weigl, Andreas (Hrsg.): Im Epizentrum des Zusammenbruchs. Wien im Ersten Weltkrieg, Wien 2013, 606 (Translation)