Anti-Semitism in other nationalities within the Habsburg Monarchy

Anti-Semitism was not only a phenomenon in the German-speaking political scene within the Habsburg Monarchy. It also had an inauspicious tradition among other nationalities in central Europe.

In contrast to the German-dominated Austrian Danube and Alpine regions, where in view of the comparatively sparse Jewish population – with the exception of Vienna and Trieste – an ‘anti-Semitism without Jews’ was to be observed, the Jewish population in the other parts of the empire was considerably larger.

Hungary had a number of historical Jewish communities, and in some parts of the country Jews made up as much as 15 per cent of the population. Whereas traditional Hungarian Judaism was established in small towns, a new centre of Jewish life developed in the flourishing city of Budapest, which was also the destination of massive migration waves of Galician and Russian Jews. In 1880 there were 71,000 Jews living in the Hungarian capital, and the population grew rapidly in the following decades. By 1900 there were 166,000 Jewish citizens (19 per cent of the population) and by 1920 as many as 216,000 (23 per cent). During the First World War Budapest thus had the second-largest Jewish community in Europe after Warsaw. Vienna had a much larger overall population and although there were almost as many Jewish citizens there, they only made up 10 per cent of the total inhabitants.

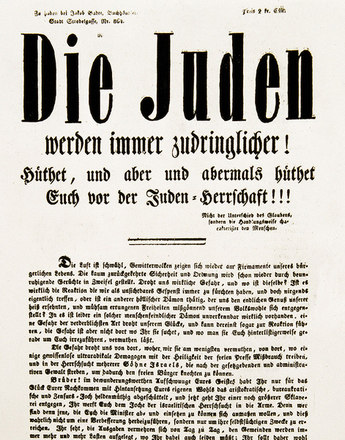

As in Vienna, the Jews of Budapest made an important contribution to the city’s cultural and economic development. The anti-Semitic propaganda of the radical nationalists used the same stereotypes, attacking the liberal Jewish bourgeoisie in the classic ‘blood and soil’ style. The Hungarian version of anti-Semitism saw the ‘mercantile’, ‘urban’ and ‘cosmopolitan’ Jew as an enemy of ‘true Hungarianness’ portrayed as ‘rural’, ‘Christian’ and ‘attached to its native soil’.

In Galicia, which had an even higher proportion of Jews than Hungary, religiously motivated anti-Semitism had additional social and economic elements. The traditional roles of the Jews in village society were as estate managers, tavern-keepers or traders in agricultural products, and they were thus a target of hate, being blamed for social grievances such as extreme poverty, alcoholism and lack of prospects. The prevalent image of the Jew was as an exploiter who profited from the plight of the defenceless peasants. Added to this was the rapid growth of the Jewish communities, in which most of the inhabitants lived in the most abject poverty, as a result of the arrival of Russian and Romanian Jews, particularly after the organized pogroms taking place in Russia from 1880 onwards. For many of them, Galicia was merely a transit station on the way to Vienna, Budapest or further west.

In Galicia, the upwardly mobile urban Jews turned their back on Yiddish as the language of the shtetl and used Polish as their lingua franca. They were nevertheless prevented from fully integrating: they were confronted by a wave of anti-Semitism from the national Polish Catholic conservative mainstream, while the Ruthenians saw the Jews as the allies and henchmen of the Polish oppressors.

The situation was somewhat better in Bohemia, although the Jews there were regarded by the Czech nationalists as agents of Germanization on account of their traditional espousal of German culture. In the second half of the nineteenth century, when a self-aware educated and wealthier Czech middle class began to develop, the Jewish bourgeoisie became more open to the Czech nationalist ideologies and was hesitatingly accepted by the liberal, free-thinking Czech elites. In Moravia, where the contrast between the urban and rural communities defined the national borders, the Jews, who lived for the most part in an urban environment, tended more to German culture, which, along with the greater influence of Catholicism, also explains the greater anti-Semitism among the Czechs there.

There was also a latent anti-Semitism in Bohemia, however. The Hilsner affair in 1899 was a notorious example. It was named after Leopold Hilsner, who was accused in an anti-Semitic reflex of a ritual murder in Polná, a small Bohemian town with an old Jewish community. It became a litmus test for the Czech political scene, which proclaimed liberal and humanist ideals but was now nevertheless in danger of falling prey to demagogic temptations.

Translation: Nick Somers

Bihl, Wolfdieter: Die Juden, in: Wandruszka, Adam/Urbanitsch, Peter (Hrsg.): Die Habsburgermonarchie 1848–1918, Band III: Die Völker des Reiches, Wien 1980, Teilband 2, 880–948

Kořalka, Jiří: Tschechen im Habsburgerreich und in Europa 1815 bis 1914. Sozialgeschichtliche Zusammenhänge der neuzeitlichen Nationsbildung und der Nationalitätenfrage in den böhmischen Ländern (Schriftenreihe des Österreichischen Ost- und Südosteuropa-Instituts 18), Wien 1991

Křen, Jan: Die Konfliktgemeinschaft. Tschechen und Deutsche in den böhmischen Ländern 1780–1918 (Veröffentlichungen des Collegium Carolinum 71), München 1995

Lukacs, John: Ungarn in Europa. Budapest um die Jahrhundertwende, Berlin 1990

Rumpler, Helmut: Eine Chance für Mitteleuropa. Bürgerliche Emanzipation und Staatsverfall in der Habsburgermonarchie [Österreichische Geschichte 1804–1914, hrsg. von Herwig Wolfram], Wien 2005

-

Chapters

- Antisemitism: A historical definition

- Jewish life in the Habsburg Empire

- Anti-liberalism – anti-capitalism – anti-Semitism

- Antisemitism as a political movement

- "I decide who is a Jew"

- The social exponents of Austrian anti-Semitism

- Anti-Semitism in other nationalities within the Habsburg Monarchy

- The Habsburg Monarchy as the guarantee of pluralistic identities

- Jewish soldiers in the Austro-Hungarian army

- The "Eastern Jews" as a pivotal point for anti-Jewish agitation

- The breakdown of the internal peace