‘We intended the strike to be a great revolutionary demonstration.’ The Social Democrats and the January Strike

The role of the Social Democrats under their Party Chairman Victor Adler during the days of the strike has remained a controversial issue to the present day. If at that time there had been a decision in favour of revolution, then this, in the opinion of radical left-wingers, would have been possible in January 1918.

In his book Die österreichische Revolution (The Austrian Revolution) (1923), Otto Bauer defended the practical political considerations which led the leadership of the Social Democratic Party to hold back during the January strike in 1918. The party executive did not want to have the law of action forced on it by the revolutionary core of the strike movement: ‘We intended the strike to be a large-scale revolutionary demonstration. We could not allow it to escalate into the revolution. Hence we had to ensure that the strike came to an end.’

Looking back, Otto Bauer spoke of a sober assessment of the strike movement at that time, whose realistic chances of success would have been small because of the lack of support from the Czech workforce. ‘Nothing was a more important symptom for us during the January strike than the attitude of the Czech workers. The only place that was affected by the strike was Brno, where the leaders were centralists linked to the trade unions in Vienna, The whole large Czech area, where the Czech Social Democrats were the leaders, remained quiet.’ Moreover, a revolution would have resulted in an immediate invasion by German troops: ‘German armies would have occupied Austria, just as a little later they occupied incomparably larger areas in Russia and the Ukraine. … Austria would have become a theatre of war.’

On the one hand the party leadership around Victor Adler were praised for their ‘clever behaviour’, since they had brought the strike movement under control and managed to get a majority of the Workers’ Council to vote for the termination of the strike. On the other hand there was talk of a ‘policy of keeping things quiet’ and of a deliberate failure on the part of the leadership, who were unprepared and had not made use of the revolutionary mood of the mass of workers or had not wanted to do so. In December 1918 Egon Erwin Kisch commented, ‘What is the use of the mood of masses under such a leadership? What use is the strength of a wrestler’s body to him if his arms are paralyzed?’ A report drawn up at the Vienna police headquarters on the party conference of the Lower Austrian Social Democrats in February 1918 mentions strong criticism of the party leadership, according to which the Vienna Workers’ Council was not ‘fit to lead strikes but “to strangle” them’. And many speakers had complained that the party executive had not made any attempt to get the release from prison of Fritz Adler and the other persons arrested in the wake of the strike. Victor Adler is reported to have replied tersely that it would go against the grain for him ‘to rouse a few sensation-seeking women on account of his son’.

In fact the events of January 1918 did have an enormous influence on the war, the subsequent development of the monarchy and the beginning of the republic: they mark the beginning of a movement to establish soviets in Austria and the onset of the internal destabilization of the state. Next came mutinies in the navy, which led to the demobilization of troops in the months up to October and November, as well as further waves of strikes in Lower Austria and Vienna. Suddenly the Social Democrats were in an incomparably stronger negotiating position than they had been. Deeply disillusioned left-wing radicals decided to break with the Social Democrats and then in November founded the Communist Party.

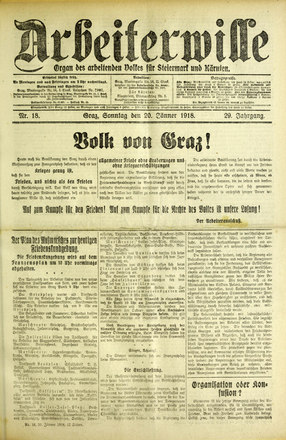

‘Begin the fight for peace! Begin the fight for the people’s rights is our watchword!’ The issue of the Arbeiterwille (Will of the Workers) newspaper published on 20 January 1918 demands a general peace without war reparations.

In the Arbeiterwille of 21 January 1918 there is a call for the resumption of work following the statement by the government which is regarded as ‘satisfactory’.

Translation: Leigh Bailey

Bauer, Otto: Die Österreichische Revolution, Wien 1923

Hautmann, Hans: Jänner 1918 – Österreichs Arbeiterschaft in Aufruhr. Unter: http://www.klahrgesellschaft.at/Referate/Hautmann_Jaennerstreik.html (20.6.2014)

Maderthaner, Wolfgang: Die eigenartige Größe der Beschränkung. Österreichs Revolution im mitteleuropäischen Spannungsfeld, in: Konrad, Helmut/Maderthaner, Wolfgang: Das Werden der Ersten Republik. ... der Rest ist Österreich, Bd. I, Wien 2008, 187-206

Stadler, Karl R.: Die Gründung der Republik, in: Skalnik, Kurt: Auf der Suche nach der Identität, in: Weinzierl, Erika/Skalnik, Kurt: Österreich 1918–1938. Geschichte der Ersten Republik, Graz/Wien/Köln 1983, 55-84

Zitate:

„We intended the strike ...", „Nothing was a more important ...", „German armies would have occupied...": Bauer, Otto: Die Österreichische Revolution, Wien 1923. Unter: http://archive.org/stream/diesterreichis00baueuoft/diesterreichis00baueu... (20.6.2014) (Translation)

„What is the use of the mood ...": Der freie Arbeiter, 7.12.1918, 37 (Translation)

„fit to lead strikes but ...", „to rouse a few sensation-seeking ...": zitiert nach: Neck, Rudolf: Österreich im Jahre 1918. Berichte und Dokumente. Wien 1968, 26f. (Translation)

-

Chapters

- The End of Monarchy, the Birth of New States

- 12 November 1918

- The Path to 12 November: ‘If there is no peace then there will be a revolution here’

- ‘We intended the strike to be a great revolutionary demonstration.’ The Social Democrats and the January Strike

- Was There an Austrian Revolution or Not?

- A Marxist on Ballhausplatz – Otto Bauer Takes Over Foreign Policy

- The End of the Dream: the Failure of Bauer’s Foreign Policy