Anti-war literature as a bestseller: Im Westen nichts Neues (All Quiet on the Western Front)

Erich Maria Remarque was called up for war service at the age of eighteen and shortly afterwards was wounded by a piece of shrapnel from a grenade. Marked by his experience of war, he developed an anti-militarist attitude, which finds expression in his novel All Quiet on the Western Front (1928).

This novel, which is claimed to be the most read book in the world after the Bible, reached a total print run of at least 20,000,000 copies in some fifty translations. An extraordinarily intensive and expensive advertising campaign by Ullstein, the publishers, led rapidly to the biggest ever success for a book in the history of German literature – by 1930 one million copies had already been sold. This led the publishing house to print 1,000 copies in braille and distribute them free-of-charge to ex-soldiers who had been blinded in the war.

The great effect the novel had on the outside world provoked contradictory responses to its content and to the person of Remarque. Those on the right saw it as an attempt to taint the image of soldiers at the front, while those on the left saw it, to put the matter simply, exclusively as anti-war literature.

In 1930 the novel was filmed; Goebbels, then Gauleiter in Berlin, had his SA troops disrupt cinema performances, for example by setting off smoke and stink bombs or by releasing mice. Subsequently performances were banned on the grounds of ‘damage to the reputation of Germany abroad’. Remarque’s books were publicly burned in 1939 and the author was stripped of his German citizenship.

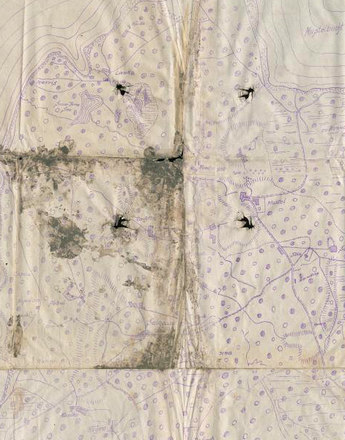

The protagonist of the novel, Paul Bäumer, who volunteers for military service while still at school, depicts the First World War from the perspective of an ordinary soldier. The young recruits lose their initial enthusiasm for the war while still training at their home base. ‘Brutalized in a strange and melancholy way’, they become ‘human animals’. What shapes them is more the comradeship than death and survival at the front, which are experienced in the midst of ‘drumfire, despair and the men’s brothel’. The war estranges those who have remained at home behind the lines from those who have been at the front, because the latter can find no words, no language, to communicate their war experiences.

Remarque places a short text at the beginning of his novel by way of a programme:

This book is meant neither as an accusation nor as a confession. Its aim is solely to attempt to give an account of a generation which was destroyed by the war – including those who managed to escape its shells.

Bäumer did not escape its shells; in the final, soberly written paragraph Remarque notes:

He fell in October 1918, on a day which was so quiet and calm on the whole front that the army report consisted of just one sentence, ‘All quiet on the Western front’.

He had slumped forwards and was lying as if sleeping on the ground. When they turned him over they saw that he could not have suffered for very long – his face had such a composed expression, as if he was almost content that things had turned out thus.

In a key passage Bäumer and his comrades discuss the function and the sense of the war. Remarque poses the timelessly valid question:

‘Why is there war at all then?’ Tjaden asked. Kat shrugged his shoulders. ‘There must be people who benefit from the war.’ ‘Well, I’m not one of them,’ Tjaden grinned. … ‘There’ve got to be other people behind the war who want to make money out of it,’ Detering roared.

Translation: Leigh Bailey

Remarque, Erich Maria: Im Westen nichts Neues, 34. Auflage, Köln 2012

Quotes:

„Brutalized in a strange and melancholy way’ …“: Remarque, Erich Maria: Im Westen nichts Neues, 34. Auflage, Köln 2012, 23 (Translation)

„human animals’“: ebd., 46 (Translation)

„drumfire, despair and the men’s brothel“: ebd., 198 (Translation)

„This book is meant neither …“: ebd., 9 (Translation)

„He fell in October 1918 …“: ebd., 199 (Translation)

„Why is there war …“: ebd., 142f. (Translation)

-

Chapters

- ‘Rabble of words’ – Writers in the War

- ‘An area to which only those who are (un)employed there have access.’

- The war after the war – reflection, homecoming and review

- ‘ … with deadly weapons, the golden plains’: Grodek as the legacy of the poet Georg Trakl

- ‘Guilt is always beyond doubt!’ Franz Kafka’s 'In der Strafkolonie' (In the Penal Colony)

- I did not want it: Die letzten Tage der Menschheit (The Last Days of Mankind)

- Anti-war literature as a bestseller: Im Westen nichts Neues (All Quiet on the Western Front)

- ‘What remained was a mutilated trunk that bled from every vein.’ Stefan Zweig and his "World of Yesterday"