Did the Great Powers ‘stumble’ into the First World War, as is often claimed? Or were there powerful ‘material’ interests behind the official political rhetoric that made the war appear desirable?

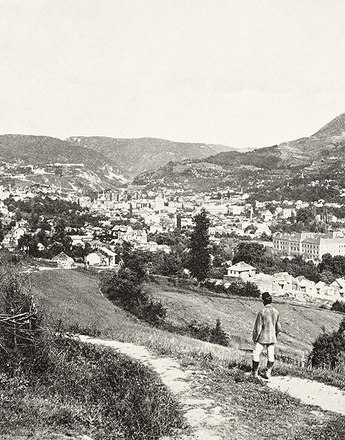

The First World War was seen by many contemporaries and historians as an ‘imperialist’ war. This means above all that it did not break out unexpectedly or accidentally. The last decade before 1914 was a period of increasing political tension between the major European powers in various parts of the world, on the Balkans, in Africa and on the oceans of the world. At the same time, the countries were also attempting to secure their sphere of influence commercially. Austria-Hungary played a subordinate role in the world concert of imperialism. Leaving aside the 1914 attempt, in concert with Italy, to influence the foundation of the national bank of the newly created Albania, the Empire’s only ‘colonial’ conquest was to acquire control over Bosnia-Herzegovina, which it occupied in 1878 and annexed in 1908. Thus it might well have been no accident that the assassination of the heir to the Austrian throne and his wife, which triggered the Great War, occurred precisely in Sarajevo.

The assassination of 28 June 1914, although a humiliation for Austria-Hungary, was of merely regional significance. It was only due to the alliances between the Great Powers in Europe that it developed into the famous spark on the powder keg that detonated the world. This initial view of a ‘local’ constellation may explain the carelessness with which the Empire’s politicians and generals trivialised the risk of it expanding into a European war, and launched a war that they, blind to the consequences of their actions, regarded as a dispute between Serbia and Austria-Hungary.

It is some years ago that the German historian Fritz Fischer, in his book Germany's aims in the First World War (published in German in 1961), triggered the debate on the interconnections between the political and economic spheres with his provocative theory that the German Reich did not ‘stumble’ into the armed dispute but was deliberately pursuing a hegemonial agenda by encouraging the Austro-Hungarian monarchy to strike back, while at the same time thwarting any attempt to settle the conflict peacefully.

Without going into the details of this decade-long controversy, there can be no doubt that Austria Hungary cannot be exonerated from guilt for the outbreak of the Great War. In particular the head of the General Staff of the Austro-Hungarian army, Franz Freiherr Conrad von Hötzendorf, had long before the summer of 1914 been a prominent supporter of a preventive war against Serbia (and Italy). He regarded the Balkans as to all intents and purposes the Empire’s natural sphere of influence, even if Austria Hungary was by no means capable of exercising economic supremacy.

Translation: David Wright

Clark, Christopher: Die Schlafwandler. Wie Europa in den Ersten Weltkrieg zog, München 2013

Janz, Oliver: Der Große Krieg, Frankfurt am Main 2013

Leonhard, Jörn: Die Büchse der Pandora: Geschichte des Ersten Weltkrieges, München 2014

Rauchensteiner, Manfried: Der Erste Weltkrieg und das Ende der Habsburgermonarchie, Wien/Köln/Weimar 2013

-

Chapters

- The underlying causes of the First World War

- The folly of the erstwhile rulers

- Schumpeter’s imperialism theory: Did big business press for war?

- A state living beyond its means

- Problems of the war economy

- High mark and decline of the economic war effort

- Shifts in the production structure

- The change in the social balance of power in the course of the war