Large empires such as Austria-Hungary, which had been at an advantage in the armed disputes of the 19th century because of their large populations, proved in the First World War to be incapable of bearing the burdens of modern war because of their weak economic basis.

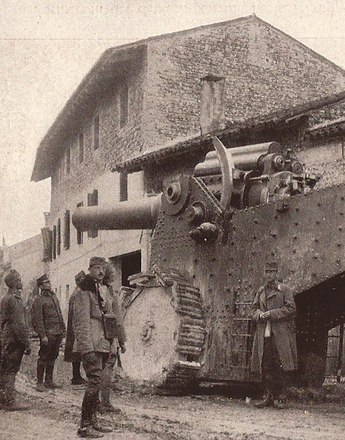

In 1915, a certain consolidation of the war economy seemed to be on the horizon. However, it took some time for the military leadership to realise that the demands of ‘modern’ warfare needed not only the uninterrupted provision of new ‘human material’ but was also developing generally to becoming a huge ‘battle of material’. In addition to the increased production of armaments in the narrow sense, this required the uninterrupted supply of raw materials and coal (as the main source of energy of not only industry but also the railways). The railways formed the backbone of the supply of soldiers, food, ammunitions and reinforcements to the front.

In order to keep war production free of social ‘obstacles’ such as a reluctance to work, sabotage and strikes, enterprises of importance to the armaments industry were subjected to military discipline by recourse to the War Service Act promulgated on 26 December 1912. At the beginning of February 1915, this covered around 1,000 companies and their employees in Cisleithania, and one year later 4,500 businesses with 1.3 million workers. The workers were classified as ‘soldiers without rank’ and the punishment for an offence could even be the death penalty.

Despite these drastic measures, it took a long time before those responsible – unprepared and fixated on a short war – at least gradually managed to gain control over the problems of the transformation into a war economy. It was only in the course of 1915 that the situation improved. However, the problems in the food sector were never satisfactorily solved by 1918, leading, as the war continued, to a permanent undernourishment of the civilian population and soldiers (which was the consequence of the conscription of farmers and agricultural workers and the lack of deliveries from Hungary).

The planning of the war economy – setting priorities in the allocation of raw materials and primary products according to military aspects – only began after a delay (the foundation of ‘War Central Offices’ from autumn 1914, even later in Hungary) and was never really brought under control. Nor was it possible to find a solution to the transport problems (and thus the supply of coal generally). Nor were any provisions made for the prisoners of war transported to the Empire. They were interned in camps, poorly nourished and therefore susceptible to epidemics. In contrast to the Second World War, they were rarely used as forced labourers in industry and mining, but very often for artisanal work (such as joinery and basket-weaving in the camps), in agriculture or for logistic activities in the staging area behind the front. Even today, we do not know how many prisoners of war were interned in Austria Hungary. Estimates vary widely, fluctuating between 1.2 and 2.3 million.

Translation: David Wright

Clark, Christopher: Die Schlafwandler. Wie Europa in den Ersten Weltkrieg zog, München 2013

Gusenbauer, Ernst: Kriegsgefangenenlager während des 1. Weltkrieges in Österreich-Ungarn und ihre Auswirkungen auf das Leben der Zivilbevölkerung, München 2000

Janz, Oliver: Der Große Krieg, Frankfurt am Main 2013

Rauchensteiner, Manfried: Der Erste Weltkrieg und das Ende der Habsburgermonarchie, Wien/Köln/Weimar 2013

Wegs, Robert J.: Die österreichische Kriegswirtschaft 1914–1918, Wien 1979

-

Chapters

- The underlying causes of the First World War

- The folly of the erstwhile rulers

- Schumpeter’s imperialism theory: Did big business press for war?

- A state living beyond its means

- Problems of the war economy

- High mark and decline of the economic war effort

- Shifts in the production structure

- The change in the social balance of power in the course of the war