Within the Monarchy as a whole, the Bosnians, i.e. the southern Slav Muslims in Bosnia, were one of the smallest ethnic groups accounting for just 1.2 per cent of the population of the empire.

The 650,000 Bosnians made up around one third of the population of Bosnia and Herzegovina. One problem with determining the size of this ethnic group was that no distinction was made in the official statistics between Serbs, Croats and Bosnians, as all speakers of this southern Slavic language were combined within the Serbo-Croat language group. More accurate figures can be obtained only by considering the religions. The proportion of Bosnians in Bosnia and Herzegovina would therefore have been the same as the percentage of Muslims, i.e. 32.3 per cent.

The Bosnians were the legacy of the Ottoman Turkish presence in the Balkans. Bosnia had been under Turkish rule since the fifteenth century and was an important outpost of Ottoman expansion in south-eastern Europe. The existence of an Islamic group within the population of Bosnia was due less to the systematic settlement of Muslims than to the conversion of regional elites to Islam. The Bosnian nobility and burghers subjected themselves to Ottoman rule and took the Muslim faith to maintain their predominant position. Sarajevo became the capital and urban centre of the Ottoman elites.

Even during the period of Turkish rule in Bosnia, the Muslims remained a minority, although they dominated the cultural and economic sectors. All public servants had to be Muslim, and most of the land was owned by a rich Muslim upper class, while the majority of the Christian population – orthodox Serbs and Catholic Croats – consisted of smallholder and tenant farmers. The presence of Sephardic Jews, driven out of Spain after the Reconquista, was a further legacy of Ottoman rule. Thanks to the Ottoman religious tolerance, important communities arose in the urban centres of the region.

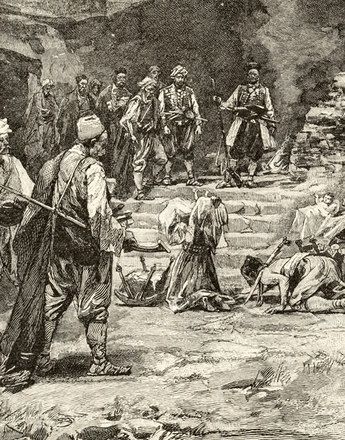

In the nineteenth century the decline and stagnation of the Ottoman Empire was felt particularly in Bosnia on account of its peripheral location. The Sultan retained only pro forma authority, and the land was more or less left to its own devices. The general social and economic crisis was aggravated by the national demands of the Slav peoples in the Balkans. Following the reorganization of the Balkans at the Congress of Berlin in 1878, Bosnia and Herzegovina were given to the Habsburg Empire and occupied by the Austrian army. They remained de iure part of the Ottoman Empire with the Sultan as its ruler, but the territory was administered by the Austro-Hungarian authorities.

The Austrian administration invested in the infrastructure of this backward country, which from being at the edge of the Ottoman Empire became an outpost of Austria-Hungary in the Balkans. The Austro-Hungarian authorities saw Bosnia as a colony of sorts, and many of the measures had a marked imperialistic character.

The multi-ethnic Habsburg empire now found itself confronted by a further ethnic group. It was hoped to persuade the Muslim Bosnians, who formed local elites, to cooperate with the occupying powers. The dominant role of the Muslim Bosnians was not therefore questioned. This conservative approach by the Austrian administration gave rise to social conflicts that further weakened the cohesion of the heterogeneous ethnic groups in the land.

The annexation of Bosnia and Herzegovina by Austria-Hungary in 1908 produced a foreign policy crisis but did little to change the situation in the land itself. The civilian administration was strengthened: the Landeschef as highest local representative of state authority, was no longer the commander of the occupying army but a civilian. In 1910 a parliament based on the model in other crown lands was convened for the first time. Its composition reflected the multi-confessional situation in the country. High religious dignitaries and representatives of cultural institutions from the various religious groups had permanent seats. The other members were chosen in three separate elections by religion, and the number of seats was proportional to the members of the various religions within the population as a whole.

Translation: Nick Somers

Buchmann, Bertrand Michael: Österreich und das Osmanische Reich. Eine bilaterale Geschichte, Wien 1999

Džaja, Srećko: Bosnien-Herzegowina in der österreichisch-ungarischen Epoche (1878–1918) (Südosteuropäische Arbeiten 93), München 1994

Hösch, Edgar: Geschichte der Balkanländer. Von der Frühzeit bis zur Gegenwart, München 1999

Rumpler, Helmut: Eine Chance für Mitteleuropa. Bürgerliche Emanzipation und Staatsverfall in der Habsburgermonarchie [Österreichische Geschichte 1804–1914, hrsg. von Herwig Wolfram], Wien 2005

-

Chapters

- The Croats in the Habsburg Monarchy

- ‘Loyal rebels: the role of the Croats in the 1848 revolution

- The question of autonomy: the Croats caught between Vienna and Budapest

- The Serbs in the Habsburg Monarchy

- ‘Serbs all and everywhere’: the Serb national programme

- The Bosnians in the Habsburg Monarchy

- Sharia under the Double Eagle: Austria-Hungary and the Bosnian Muslims

- From Illyrism to Yugoslavism: competing concepts for a southern Slav nation

- Friend or foe? The positions of the southern Slavs in the First World War