The 1848 revolution called for the dismantling of traditional hierarchies and the emancipation of nations. The leaders of the emerging Croat nation saw their opportunity for claiming their national future.

The central question was the constitutional status of Croatia within the Habsburg Monarchy. Zagreb demanded greater autonomy from Hungary, which was rejected by the Hungarians. The leaders of the Magyar nation wished to transform the historical multi-ethnic Kingdom of Hungary into a Magyar nation state, whereas the Croats saw themselves called to higher things. The national Croat programme provided for the unification of the southern Slav settlement areas with the Croats as leaders within the Illyrian movement.

Radical groups went a step further and demanded the creation of an independent state of Croats, Serbs and Slovenes. When the theoretical demands were put into practice – Croat activists started agitating in Turkish Bosnia and offered the Serbian Karađorđević dynasty leadership of a united Illyria – and threatened the Habsburg rule, alarm bells sounded in Vienna.

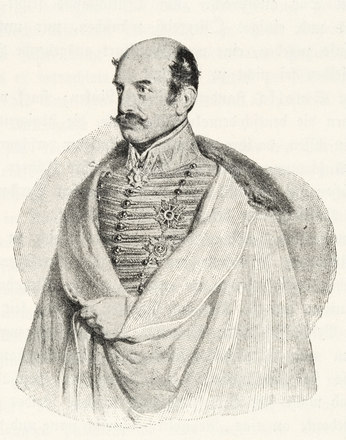

The conservative nationalist revolution supported by the nobility and led by Count Josip Jelačić (1801–59) was more to Vienna’s liking. Jelačić, an imperial military officer, was Ban of Croatia, in other words the governor and representative of the king. He was pro-Habsburg and pursued an Austro-Slav line, with the Habsburg Monarchy offering the ideal future framework for the central European Slavs, and discouraged contact by the Croat nationalists with the greater Serbia movement in Belgrade. Jelačić singled out the Magyar nationalists as the main enemy of the Croat nation. In view of the increasing Magyarization pressure – highlighted amongst other things by the demand for introduction of Hungarian instead of the traditional Latin as judicial and administrative language in Croatia – he found strong support among the Croat landed gentry.

The Croatian parliament (Sabor) convened in March 1848 declared itself the representative of the nation and demanded separation from Hungary, unification of the Croat settlement regions and social reforms, e.g. emancipation of the serfs. Under Jelačić’s leadership, the Sabor firmly opposed the political agenda of the leaders of the revolution in Hungary. The demand by Hungary for the removal of Jelačić as Ban of Croatia was ignored and the fronts hardened. The imperial government under the weak Emperor Ferdinand was powerless, although Vienna was secretly pleased that the ‘loyal rebel’ Jelačić was occupying the energies of the Hungarian revolutionaries.

The Croatian-Magyar conflict escalated in a series of military skirmishes when Jelačić led Croat troops into southern Hungary. After the situation in Hungary had further polarized under the leadership of Lájos Kossuth, who ordered a march on Vienna to provide military support for the Viennese October revolutionaries, a battle took place on 30 October 1848 near Schwechat to the south-east of the imperial capital, in which the Hungarian revolutionary troops were repulsed by Croatian units under Jelačić. At the same time, imperial troops led by Field Marshal Prince Windisch-Graetz conquered the city. The intervention of the Croat troops thus helped directly to put down the revolution in Vienna.

In the neo-absolutist regime that followed, aided in part by Jelačić’s military support, the Croatian demands for autonomy from Hungary were not met, however. The resultant conflict between Zagreb and Belgrade was welcomed in Vienna, which was able to use Croatia as a foil to the Magyar demands.

Translation: Nick Somers

Rumpler, Helmut: Eine Chance für Mitteleuropa. Bürgerliche Emanzipation und Staatsverfall in der Habsburgermonarchie [Österreichische Geschichte 1804–1914, hrsg. von Herwig Wolfram], Wien 2005

Suppan, Arnold: Die Kroaten, in: Wandruszka, Adam/Urbanitsch, Peter (Hrsg.): Die Habsburgermonarchie 1848–1918, Band III: Die Völker des Reiches, Wien 1980, Teilband 1, 626–733

-

Chapters

- The Croats in the Habsburg Monarchy

- ‘Loyal rebels: the role of the Croats in the 1848 revolution

- The question of autonomy: the Croats caught between Vienna and Budapest

- The Serbs in the Habsburg Monarchy

- ‘Serbs all and everywhere’: the Serb national programme

- The Bosnians in the Habsburg Monarchy

- Sharia under the Double Eagle: Austria-Hungary and the Bosnian Muslims

- From Illyrism to Yugoslavism: competing concepts for a southern Slav nation

- Friend or foe? The positions of the southern Slavs in the First World War