The Croat language group in the Habsburg Monarchy in 1910 numbered 2.8 million people, 5.3 per cent of the total population.

The Croats lived in both halves of the Dual Monarchy. Croatia, the heartland of the emerging Croat nation, and Slavonia were in the Hungarian half. In both of these Hungarian crown lands, which had special autonomous rights, the Croats made up 62.5 per cent of the population, and were thus the majority nationality and shapers of the national identity.

In Hungary itself, Croats were to be found as a minority in southern Hungary on the left bank of the Drau [Drava] and in western Hungary along the border with Styria and Lower Austria. They were the descendants of refugees from the western Balkans who had fled the Ottomans in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries to settle in western Hungary and to an extent along the March [Morava] in the east of Lower Austria as far as southern Moravia. Most of the new Croat settlers were gradually assimilated, and it was only at the border between the German and Hungarian language groups that they survived – and still survive today – as Burgenland Croats.

In Cisleithania, the Croats were concentrated for the most part in Dalmatia. No distinction was made there between them and the Serbs, and together, as ‘Serbo-Croats’, they made up 96.2 per cent of the population.

In the Austrian coastlands, the Croats in Istria accounted for 43.5 per cent of the population, making them one of the largest ethnic groups alongside the Italians and the Slovenes, while in Trieste they represented a minority of just 1.3 per cent.

In the Austro-Hungarian condominium of Bosnia and Herzegovina, they were the third largest group, with a 22.9 per cent share of the population, after the Serbs and Bosnians.

The historical awareness of the modern Croat nation derives from the medieval Triune Kingdom of Croatia, Slavonia and Dalmatia. Thanks to the existence of this proto-national state, the Croats, in contrast to most other language groups in the region, were able to look back on traditions of statehood, even if the Croat kingdom had been united with Hungary since 1102, making the king of Hungary simultaneously king of the Croats.

The various regions experienced diverse historical developments. Croatia itself, with its capital Agram [Zagreb], had been under Habsburg rule since 1526. Slavonia came under Ottoman domination in the sixteenth century and did not form part of the Habsburg Monarchy until the Ottomans had been driven out of Hungary around 1700.

The Turkish wars, which were fought for centuries in Croatia and Slavonia, brought about far-reaching changes in the character of the land. Large parts of the territory were separated from the rest of the country (‘civilian Croats’) through the erection of the Military Frontier and were placed as a discrete entity under the direct administration of the imperial army. The military presence and re-colonization of the devastated areas left traces in the ethnic relations in the region and created a colourful mixture of Croat, Serb but also Hungarian, German and Slovak settlements.

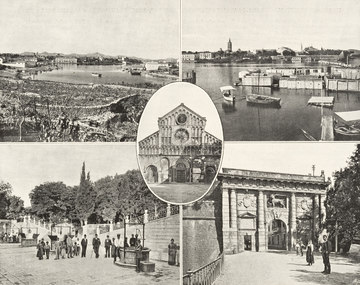

Dalmatia, by contrast, developed quite differently. It was ruled for centuries by Venice and characterized by a strong Italian cultural influence. It came permanently under Habsburg rule only through the agreements made at the Congress of Vienna in 1814/15.

In the era of emerging statehood, the Croats at the beginning of the nineteenth century were faced by similar problems as most of the other small nations in eastern central Europe. The local nobility had a Croat national awareness, but they were still a long way from a modern national society. An educated urban middle class was slow in forming because the larger towns inland were dominated by Germans or Magyars and the Dalmatian coast by Italians. The administrative, judicial and scholarly language in Croatia itself was Latin, or Italian in Dalmatia. The Croatian vernacular was cultivated only in the church, and it was from the clergy that the first language reforms came. From the mid-nineteenth century the young middle-class intelligentsia took over from the nobility as the leaders of the country. Poets and writers devoted themselves to the national cause and made initial attempts to develop a modern Croatian written language. The spelling rules were defined by language reformer Ljudevit Gaj (1809–72), a Slavo-Croat with the pan-Slav orientation typical of the time, who in 1830 published Kratka osnova hrvatsko-Slavenskoga pravopisanja (Basic principles of Croatian-Slavonic spelling).

Translation: Nick Somers

Rumpler, Helmut: Eine Chance für Mitteleuropa. Bürgerliche Emanzipation und Staatsverfall in der Habsburgermonarchie [Österreichische Geschichte 1804–1914, hrsg. von Herwig Wolfram], Wien 2005

Suppan, Arnold: Die Kroaten, in: Wandruszka, Adam/Urbanitsch, Peter (Hrsg.): Die Habsburgermonarchie 1848–1918, Band III: Die Völker des Reiches, Wien 1980, Teilband 1, 626–733

-

Chapters

- The Croats in the Habsburg Monarchy

- ‘Loyal rebels: the role of the Croats in the 1848 revolution

- The question of autonomy: the Croats caught between Vienna and Budapest

- The Serbs in the Habsburg Monarchy

- ‘Serbs all and everywhere’: the Serb national programme

- The Bosnians in the Habsburg Monarchy

- Sharia under the Double Eagle: Austria-Hungary and the Bosnian Muslims

- From Illyrism to Yugoslavism: competing concepts for a southern Slav nation

- Friend or foe? The positions of the southern Slavs in the First World War