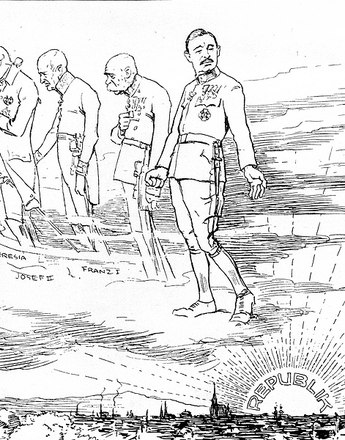

In the last years of the nineteenth century images of Austria-Hungary also began to ‘move’. The films from the late Danube Monarchy glorified the past. The myth and image of the Monarchy was created at the time and communicated in films. The visual clichés in the feature films of the inter-war and post-war years are notable for their ‘imperially beautified’ pictures and impressions of the ‘quiet and pleasant’ life in the Monarchy.

The film documents from the imperial era are dominated by the ‘magic of the uniform’, parades and processions, aristocratic celebrations and especially those of the ruling house and show nothing of poverty and exclusion. The films portray the pleasant side of Sunday and holiday leisure, with the ‘masses’ enjoying all the fun of the fair. One spectacle that attracted large numbers to the Prater in 1913 was the Adriatic exhibition – the last major show of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy before the First World War. Famous buildings on the Adriatic coast were reconstructed along a specially built canal, where the steamship Wien lay at anchor with a restaurant on board. Buildings included a campanile, the Church of St George in Lovran, the city gate of Zadar and the Rector’s Palace in Ragusa (now Dubrovnik). Visits by the king and emperor were welcomed at major projects, as can be seen in the film Emperor Franz Joseph I Opens the Adriatic Exhibition in Vienna (A 1913). Popular pictures like this were enjoyed equally by the ruling house and its subjects.

An annual highpoint was the birthday of Franz Joseph I, celebrated on 18 August in a general tribute to the emperor. Cinematography captured moments like this, as can be seen in the film Tribute to the Emperor in the Imperial and Royal Prater in Vienna (A 1911). It showed smartly dressed boys and girls, policemen and sailors, ladies and gentlemen from respectable society, but also urban and rural proletariat milling around the Prater in their Sunday best. There is more to see than usual in this film. No one wanted to miss the annual parade celebrating the assumption of office of Emperor Franz Joseph I. In the background can be seen the Giant Ferris Wheel and the speeding carriages of the elevated Scenic Railway. Everything appears to be in motion, with clusters of people gathering only in a few places, listening to the theatrically gesticulating barkers as they try to persuade customers to visit their attractions. Although these earlier pictures of the Tribute to the Emperor in the Imperial and Royal Prater in Vienna are silent, the energetic sweep of the camera makes it easy to imagine the hubbub of voices, the rattling and squeaking of the mechanical rides, and the seductive calls of the fairground barkers. This silent film somehow manages in this way to make plenty of noise.

Translation: Nick Somers

Moritz, Verena: Vergangenheitsbewältigung, in: Moritz, Verena/Moser, Karin/Leidinger, Hannes: Kampfzone Kino. Film in Österreich 1918-1938, Wien 2008, 141-172

Storch, Ursula: Eine Reise um die Welt – im Wiener Prater, in: Dewald, Christian/Schwarz, Werner Michael: Prater Kino Welt. Der Wiener Prater und die Geschichte des Kinos, Wien 2005, 101-125

-

Chapters

- Imperial and Royal myth in film

- Presentation of the imperial household: pictorial icons

- What the films didn’t show 1: Social contrasts

- What the films didn’t show 2: Religious diversity

- What the films didn’t show 3: nationalist conflicts

- Lack of resources and wartime financial difficulties on film

- Film documents: after the disaster