The Congress of Berlin in 1878 was a textbook example of two-tier diplomacy characterized by the arrogance of the major powers with regard to the smaller nations and decisions being made over their heads that were to have fateful consequences.

The aim of this diplomatic summit conference was to reorganize the Balkans. Apart from Germany as the host nation, it was attended by Austria-Hungary, Russia and Great Britain. Significantly, the Ottoman Empire was not given an active role but invited only as an observer.

Under Bismarck’s leadership, Germany, which had no direct interests in the Balkans, acted – not completely selflessly – as mediator. Berlin, Vienna and London were all concerned to curb Russia’s influence in the Balkans, and this was reflected in the outcome. The Tsar obtained only small territorial gains in Bessarabia, in blatant contrast to the significance and military strength of Russia in the region.

Bulgaria became an independent tributary principality with only symbolic dependence on the Ottoman Empire. It was also promised the semi-autonomous Eastern Rumelia, thereby thwarting Russia’s desire for occupation.

The winners were Romania, Serbia and Montenegro, which were now finally released from Ottoman rule and became independent states. As they also obtained massive territorial gains from the failing Ottoman Empire, they were persuaded to support the decisions made at the Congress.

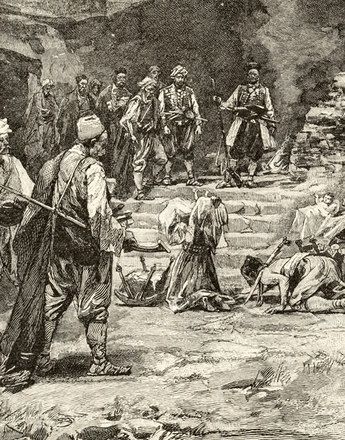

Austria-Hungary was also a beneficiary. Its ambitions in Bosnia and Herzegovina were supported and Vienna was able to gain agreement to a military occupation. The assumption of power was not bloodless, however, because local potentates put up partisan resistance to the military occupation. A further territorial engagement by Austria-Hungary in the region was the garrisoning of the Sanjak of Novi Pazar, a strip of land separating Serbia from Montenegro and the only link between Bosnia and Herzegovina and the rest of the European part of the Ottoman Empire. This strategically vital territory was also occupied by the Austrian army. In spite of the presence of Austrian troops, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Novi Pazar remained nominally part of the Ottoman Empire with the Sultan as their head of state, although the territories were now administered by Austro-Hungarian authorities.

As a further outcome of the Congress, the alliance between Austria-Hungary and Germany was confirmed, since Vienna was reliant on a strong partner to counter Russia. One direct result was the conclusion of the Dual Alliance between Berlin and Vienna in 1879.

For Austria-Hungary, the Congress of Berlin was a success in terms of foreign policy, but it was to prove a disaster as far as domestic policy was concerned. The occupation of Bosnia and Herzegovina aggravated the nationality question, as the strengthening of the southern Slav element upset the delicate ethnic balance. The Bosnian question ultimately toppled the established liberal parties in Austria and Hungary, who felt committed to the ‘empire idea’. New and more radical national parties followed. Representatives of the German nationalists and extreme Magyars regarded the occupation of this economically backward region merely as the craving of the Habsburg dynasty to assert itself and in conflict with national interests.

Translation: Nick Somers

Buchmann, Bertrand Michael: Österreich und das Osmanische Reich. Eine bilaterale Geschichte, Wien 1999

Džaja, Srećko: Bosnien-Herzegowina in der österreichisch-ungarischen Epoche (1878–1918) (Südosteuropäische Arbeiten 93), München 1994

Hösch, Edgar: Geschichte der Balkanländer. Von der Frühzeit bis zur Gegenwart, München 1999

Rumpler, Helmut: Eine Chance für Mitteleuropa. Bürgerliche Emanzipation und Staatsverfall in der Habsburgermonarchie [Österreichische Geschichte 1804–1914, hrsg. von Herwig Wolfram], Wien 2005

-

Chapters

- Under the crescent: the Ottoman Empire and Europe

- ‘The Sick Man of Europe’ – a major power in decline

- The ‘Balkanization’ of the Balkans – the nuisance of popular freedom struggles

- Bosnia and Austria’s aspirations in the Balkans

- The Congress of Berlin and the division of the Balkans

- The 1908 annexation crisis

- The 1912/13 Balkan crisis – prelude to world war