Musical Innovations in the First World War

-

Advertisement for a “Phonola piano player” by the Hupfeld company (Berlin)

Copyright: Phonolamusic, Wien

-

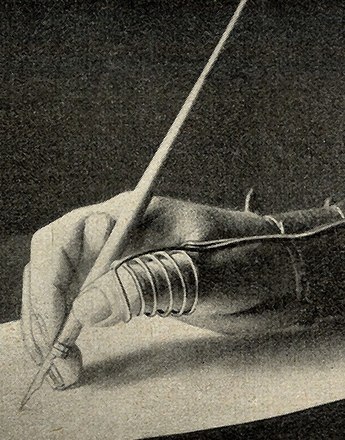

Announcement for Das Buch des Einarmigen by Géza Zichy, newspaper extract from: Oesterreichisch-ungarische Buchhändler-Correspondenz (No. 43) of 28 October 1914

Copyright: ÖNB/ANNO

Partner: Austrian National Library

As far as the history of music is concerned, the First World War did not mark a significant turning-point. This had occurred several years earlier with the advent of atonal music, and for many contemporaries it was this that represented a major catastrophe of a different kind. What the war marked was rather a sharp drop in the production of music, with hardly any really great works being written. Musical life was also adapted to war service within a very short time, and especially at the beginning of the war, when composers and performers were meant to make their contribution to mobilization, their productivity was considerable. What innovations there were resulted primarily from technical developments and the consequences of the war.

The phonograph, introduced by Thomas Edison in 1877, made it possible to record and reproduce sound for the first time. As a result the Phonogram Archive of the Imperial Academy of Sciences, at the suggestion of the War Ministry, collected recordings of soldiers’ songs in all the languages of the monarchy, which were then also made available to the Musical History Headquarters (Musikhistorischezentrale/MHZ). In Germany the Phonographic Commission was established in 1915; it carried out a secret mission in German internment camps, making spoken word and music recordings of prisoners, and was thus able to produce more than 1,600 gramophonic studies in some 250 languages. The resulting sound archive was added to during the Second World War, with further recordings of prisoners of war being made, especially of African prisoners in France.

In addition to the traditional live performances, in the First World War records could also be used to spread propaganda messages and music. However, the production of records fell sharply at the beginning of the war and recovered only slowly after 1918.

In Leipzig in 1902 Ludwig Hupfeld developed the Phonola, a form of the pianola for playing piano rolls. Known as the ‘player piano’, it enjoyed great popularity in high society. For the pianola a collection called ‘Hupfeld’s World War 1914 Original Tone Picture’ was produced, to which a supplement was added in 1915. The material includes titles which are still familiar today, like the regimental march of the ‘Hoch- und Deutschmeister’ and popular Viennese songs like Wien du Stadt meiner Träume (Vienna, City of My Dreams) and Mei Mutterl war a Wienerin. When the USA entered the war American dance hits also appeared on piano rolls, the most popular being the song Over There. The player pianos were also used for entertainment on warships, for example the German armoured cruiser Yorck and the Austro-Hungarian warship Arpad.

Since the gut strings that had been used before the war could no longer be produced in sufficient quantities, string instruments had to use steel strings; this had a lasting effect on the way that pieces of music sounded.

The war also turned musicians into invalids. There were not many of them who could later resume their career; one who did so was Paul, the brother of the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein. Leading composers of the contemporary musical scene wrote piano concertos for the left hand specially for him, among them Maurice Ravel, Richard Strauss, Sergei Prokofiev, Franz Schmidt and Benjamin Britten. The Czech composer Leoš Janáček wrote his Capriccio for one hand on the piano, flute, two trumpets, three trombones and tenor tuba for the pianist Otakar Hollmann, who had suffered the same fate as Paul Wittgenstein.

Translation: Leigh Bailey

Lautarchiv am Institut für Musikwissenschaft und Medienwissenschaft. Unter: http://www.sammlungen.hu-berlin.de/sammlungen/78/ (20.06.2014)

Soldatenlieder der k .u. k. Armee. CD mit Kommentaren von Oskar Elschek. [Tondokumente aus dem Phonogrammarchiv], 2012. Unter: http://verlag.oeaw.ac.at/index.phtml?act=ps&aref=1947 (20.06.2014)

Sommer, Isabella: Die Phonola – ein gesellschaftlich und musikhistorisch relevantes Medium zur Zeit des Ersten Weltkriegs, Wien 2013. Unter: http://www.phonolamusic.at/index.php?id=28 (20.06.2014)

Suchy, Irene et al. (Hrsg.): Empty sleeve: Der Musiker und Mäzen Paul Wittgenstein, Innsbruck 2006

-

Chapters

- ‘Long jackets instead of Tailcoats’ – The Music Business in Times of Austerity

- Arousing Patriotic Sentiments in the Concert of Nations

- ‘In War the Muses Learn How to Serve’

- Serious Times – Serious Art

- ‘I’d like to dance, I’d like to shout for joy’ – Popular Music in the First World War

- ‘German Musical Life and How to Delouse It’ – Music for Use in the War

- ‘What the soldier in battle dress is singing now will be sung by the entire German people in rare unity.’ – Soldiers’ Songs as Collectors’ Items

- ‘It’s Hugo’s damned duty not to die for the fatherland before I’ve got my Act III.’ – Richard Strauss and the First World War

- Militarism and Terror Set to Music

- ‘La Victoire en chantant’ – The French chanson in the First World War

- Musical Innovations in the First World War

- Composers’ Fates: War, Death and the Longing for Peace and Overcoming Memories

- Star Composers and the Great War