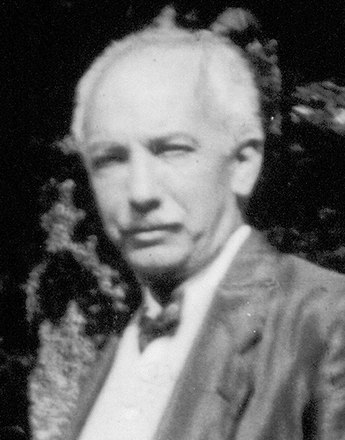

‘It’s Hugo’s damned duty not to die for the fatherland before I’ve got my Act III.’ – Richard Strauss and the First World War

In an exchange of letters, the composer Richard Strauss and his librettist Hugo von Hofmannsthal (or in some cases Gerty, his wife) expressed their views on the First World War in a form which was sometimes ironic and sarcastic, sometimes patriotic. However, for Strauss what was most important was not so much commenting on contemporary events as the effect these had on his own personal state of mind.

On the day before the official beginning of the war Richard Strauss was worried about the whereabouts of Hugo von Hofmannsthal and tried to find this out from his home in Garmisch. ‘Poets’, Strauss commented, ‘really could be left at home when there is so much cannon fodder available elsewhere in the form of critics, producers with their own ideas, actors specializing in Molière, and so on.’ Strauss was in the middle of work on the third act of his opera Die Frau ohne Schatten (The Woman without a Shadow), which he completed in 1917, although it did not receive its first performance until after the war, as its subject made it seem unsuitable for wartime. Strauss’s reaction to this unwelcome disruption of his work was to wish: ‘May the devil take those damned Serbs!’ He was in a much better mood a few weeks later as a result of the ‘great victory’ of the German army at Metz on 20 August and the completion of his third act: ‘It’s Hugo’s damned duty not to die for the fatherland before I’ve got my third act, which, I hope, will lead to even more honour than a fine obituary in the Neue Freie Presse newspaper. At the same time he hopes that ‘this country and people’ – the phrase merges Germany and Austria – are only at the beginning of a great development and really must and will achieve hegemony over Europe’.

During the war Strauss swung between hopes of victory and fears for ‘dying Austria’. He increasingly condemned the war as such, not least because of the material restrictions it meant for art: ‘the Emperor is cutting the fees at the Court Opera House; the Duchess of Meiningen has sacked her orchestra; Reinhardt is performing Shakespeare; the theatre in Frankfurt is peforming Carmen, Mignon, Les contes d’Hoffmann – who can make head or tail of the German people with their mixture of genius and lack of talent, heroism and servility. Towards the end of the war Strauss appealed to reason, which he felt could be promoted not least by the inherent ability of music to bring peoples together – presumably including his own music.

In the end Richard Strauss was among those who profited from the war, because the way in which the music business was largely restricted to performances of works by German and Austro-Hungarian composers meant that his works were among those that were given preference in theatre programmes. In 1915 he conducted the first performance of his Alpensinfonie (Alpine Symphony) in Dresden and in October 1916 a revised version of his opera Ariadne auf Naxos (Ariadne on Naxos) at the Court Opera in Vienna. Julius Korngold reported on the glamorous premiere in a highly positive way in a lengthy commentary:

One has to praise and praise again: the Court Opera has shown itself at its best. And the audience were also at their best, on a par with the work. They enjoyed this very unusual operatic music in its mature sweetness with great understanding and gave its creator a tumultuous ovation.

Der Rosenkavalier (The Knight of the Rose) was also in great demand in German-language theatres, with 100 performances being given in Dresden alone between the premiere in 1911 and the end of the war.

Translation: Leigh Bailey

Freies Deutsches Hochstift / Frankfurter Goethe-Museum (Hrsg.): Österreichs Antwort. Hugo von Hofmannsthal im Ersten Weltkrieg, Frankfurt 2014. Unter: http://www.goethehaus-frankfurt.de/ausstellungen_veranstaltungen/ausstellungen/wechselausstellung/osterreichs-antwort-hugo-von-hofmannsthal-im-ersten-weltkrieg/140407-hofmthal-leseheft-12rz-web2.pdf (20.06.2014)

Korngold, Julius: Hofoperntheater. („Ariadne auf Naxos“), in: Neue Freie Presse vom 5.10.1916, 1-5

Schuh, Willi (Hrsg.): Strauss, Richard, Hofmannsthal, Hugo von: Briefwechsel, München 1990

Quotes:

all quotes from letters: Schuh, Willi (Hrsg.): Strauss, Richard, Hofmannsthal, Hugo von: Briefwechsel, München 1990 (Translation)

„One has to praise and praise again ...“: Korngold, Julius: Hofoperntheater. („Ariadne auf Naxos“), in: Neue Freie Presse vom 5.10.1916, 1-5 (Translation)

-

Chapters

- ‘Long jackets instead of Tailcoats’ – The Music Business in Times of Austerity

- Arousing Patriotic Sentiments in the Concert of Nations

- ‘In War the Muses Learn How to Serve’

- Serious Times – Serious Art

- ‘I’d like to dance, I’d like to shout for joy’ – Popular Music in the First World War

- ‘German Musical Life and How to Delouse It’ – Music for Use in the War

- ‘What the soldier in battle dress is singing now will be sung by the entire German people in rare unity.’ – Soldiers’ Songs as Collectors’ Items

- ‘It’s Hugo’s damned duty not to die for the fatherland before I’ve got my Act III.’ – Richard Strauss and the First World War

- Militarism and Terror Set to Music

- ‘La Victoire en chantant’ – The French chanson in the First World War

- Musical Innovations in the First World War

- Composers’ Fates: War, Death and the Longing for Peace and Overcoming Memories

- Star Composers and the Great War