‘I’d like to dance, I’d like to shout for joy’ – Popular Music in the First World War

-

Military band of barracks hospital II, photo, 1918

Copyright: Wiener Volksliedwerk

-

Opening performance of the operetta "Gold gab ich für Eisen" by Emmerich Kálmán poster, 1914

Copyright: Wienbibliothek im Rathaus

Partner: Wienbibliothek im Rathaus – Vienna Library in the City Hall -

Poster announcing “Fürstenliebe”, an operetta by Leo Fall, 1916

Copyright: Wienbibliothek im Rathaus

Partner: Wienbibliothek im Rathaus – Vienna Library in the City Hall -

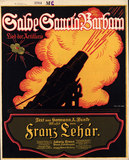

Franz Lehár: “Salve Sancta Barbara. Song of the artillery”, title sheet of a printed music, 1916

Copyright: Wienbibliothek im Rathaus

Partner: Wienbibliothek im Rathaus – Vienna Library in the City Hall -

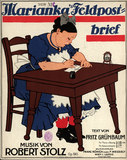

Robert Stolz: “Marianka’s field post letter”, title page of a printed music, 1915

Copyright: Wienbibliothek im Rathaus

Partner: Wienbibliothek im Rathaus – Vienna Library in the City Hall

Despite the demand for a return to serious art not even the First World War could really reduce the popular appeal of ‘light music’. Both at home as well as at the front pieces of music which by nature were meant for entertainment enjoyed great popularity. This genre too adopted patriotic content and thus followed the contemporary trend.

Emmerich Kálmán’s Csárdásfürstin (The Gypsy Princess), with a plot and music where the blissful lilt of the waltz and the fiery blood of the czardas meet, had a dazzling premiere at the Johann-Strauss-Theater in Vienna in 1915 and had more than 500 further performances by the end of war. In 1914 Kálmán had already supplied his first patriotic contribution to the war, the musical play Gold gab ich für Eisen (I Gave Gold for Iron). In 1916 Die Rose von Stambul (The Rose of Stamboul) by Leo Fall celebrated its premiere in the Theater an der Wien; the same year saw the publication of compositions by him entitled Heitere Deutsche und Österreichische Soldatenlieder (Merry German and Austrian Soldiers’ Songs). Franz Lehár, whose brother Anton made a career for himself in the Austro-Hungarian army, also satisfied the demands of wartime propaganda for patriotically motivated works. In 1927 the Volga Song from his operetta Der Zarewitsch (The Tsarevitch) provided, posthumously, as it were, a memorial in popular music to the renunciation and obedience to the fatherland that characterized a soldier’s fate.

Together with Fall, Lehár and Kálmán, Oscar Straus is also regarded as one of the most important representatives of the so-called ‘silver age’ of operetta (from the turn of the century to approximately 1920). However, unlike them he did not support the war by composing militaristic music. Robert Stolz, who had been the musical director of the Theater an der Wien from 1905 to 1907, did war service from 1914 to 1918, for some of the time as the bandmaster of the Imperial and Royal Regiment no.4, known as the ‘Hoch- und Deutschmeister’, whose regimental march was provided with a wartime version by August Jurek. It is less well known that it was during the war that Robert Stolz composed songs that became all-time hits like Wien wird bei Nacht erst schön (Vienna does not become beautiful until night falls), Im Prater blüh’n wieder die Bäume (In the Prater the trees are in blossom again) and Das ist der Frühling in Wien (That is spring in Vienna).

It was also during the war that Rudolf Sieczynski became famous thanks to some of his Viennese songs, including his first work, Wien, du Stadt meiner Träume (Vienna, City of My Dreams), composed in 1912 but not published until 1914. Sieczynski himself said of his song, for which he wrote a special wartime version of the lyrics, that it became ‘popular in particular during the war … with the soldiers in the field, who were thinking longingly of home’.

Even if we are threatened by war and hardship,

We submit to this with God.

We stand united with our German friend,

For firm and loyal stands the watch on the Rhine.

Whether young or old, everyone is looking lively

And ready to go into battle for the Emperor.

We give our possessions, we give our blood,

For Austria will last forever.

So, children, go happily to war,

For you are sure to return as victors.

Vienna, and only Vienna, will always be the city of all your dreams,

There where Habsburg’s banners fly,

There where the sturdy warriors stand.

Vienna, and only Vienna, will always be the city of all your dreams.

Go at once to the old Emperor,

To Vienna, to Vienna, to him.

Here it can be seen that Vienna takes on a special role as a surface onto which to project emotions in line with the spirit of the times. In Viennese popular songs an idyll of home is conjured up, in a form which, however, seems to become increasingly melancholy in the course of the war, with lines such as ‘I’d rather light up my good old pipe,’ – an old man sings, summing up his memories in a sentimental way – ‘You were fine, you dear old days.’ At the end of 1915 Turl Wiener wrote lyrics which made clear who was responsible for the end of the world of the good old days: ‘May God punish England. May He punish her!’

As the war dragged on the number of Viennese popular songs published declined considerably, one reason for this being that many musicians had been sent to the front. Here their role was to entertain the fighting troops, as well as to serve in field hospitals and prisoner-of-war camps.

Translation: Leigh Bailey

Glanz, Christian: Konjunkturritter der „großen Zeit“. Streiflichter zur Selbstmobilisierung der „leichten Muse“ in Wien., in: Bungart, Julia et al. (Hrsg.): Wiener Musikgeschichte. Annäherungen – Analysen – Ausblicke. Festschrift für Hartmut Krones, Wien 2009, 353-364

Mochar, Iris: Zum Wienerlied im Ersten Weltkrieg, in: bockkeller – Die Zeitung des Wiener Volksliedwerks, Ausgabe 1/2014, 5-8

Pfoser, Alfred: „Hoch der Rock, die Waffen nieder!“ Im Wien des Ersten Weltkriegs ging das Leben weiter. Und das Nachtleben konnte sich erst entfalten, in: Der Falter 01-02/2014, unter: http://www.falter.at/falter/2014/01/07/hoch-der-rock-die-waffen-nieder/ (20.06.2014)

Tonaufnahme „Wien, Du Stadt meiner Träume" (Kriegsversion; Albert Schäfer 1915). Unter: http://www.v2movie.de/vid/albert-schaeffer-tenor-wien-du-stadt-meiner-traeume-kriegstext-1915/aHR0cDovL3d3dy55b3V0dWJlLmNvbS93YXRjaD92PWNNcTVYWEZmMlh3/ (20.06.2014)

Tonaufnahme „Wolgalied“ (Richard Tauber). Unter: http://www.richard-tauber.de/2011/07/o-8306/ (20.06.2014)

Tonaufnahme „Im Prater blüh’n wieder die Bäume“ und „Wien, Du Stadt meiner Träume“ (Richard Tauber). Unter: http://www.richard-tauber.de/2011/07/o-8341/ (20.06.2014)

Quotes:

„popular in particular during the war ...": zitiert nach: Weber, Ernst: Schne Liada, in: Fritz, Elisabeth Th., Kretschmer, Helmut (Hrsg.): Wien Musikgeschichte. Teil 1: Volksmusik und Wienerlied, Wien 2006, 314, zit.iert nach Mochar, Iris: Zum Wienerlied im Ersten Weltkrieg, in: bockkeller – Die Zeitung des Wiener Volksliedwerks, Ausgabe 1/2014, 5-8, hier: 7 (Translation)

„I’d rather light up my good ...": Original-Couplet. Text: Turl Wiener und Franz Aicher. Musik: R.V. Werau, Op. 420. Wien 1915 (Translation)

-

Chapters

- ‘Long jackets instead of Tailcoats’ – The Music Business in Times of Austerity

- Arousing Patriotic Sentiments in the Concert of Nations

- ‘In War the Muses Learn How to Serve’

- Serious Times – Serious Art

- ‘I’d like to dance, I’d like to shout for joy’ – Popular Music in the First World War

- ‘German Musical Life and How to Delouse It’ – Music for Use in the War

- ‘What the soldier in battle dress is singing now will be sung by the entire German people in rare unity.’ – Soldiers’ Songs as Collectors’ Items

- ‘It’s Hugo’s damned duty not to die for the fatherland before I’ve got my Act III.’ – Richard Strauss and the First World War

- Militarism and Terror Set to Music

- ‘La Victoire en chantant’ – The French chanson in the First World War

- Musical Innovations in the First World War

- Composers’ Fates: War, Death and the Longing for Peace and Overcoming Memories

- Star Composers and the Great War