‘German Musical Life and How to Delouse It’ – Music for Use in the War

In the nineteenth century music was normally considered to be unpolitical. In the twentieth century and especially in the First World War it became increasingly political. In doing so it became functional, was in many cases forced into a pseudo-nationalist context, and was meant to contribute to moral mobilization.

From the beginning of the war countless special events of a patriotic nature were held. Whether big or small, their aim was to win over the public for the war and national or state interests. Musical journals began to print patriotic songs for these events. In 1915 the musicologist Arther Seidl published in one such journal, the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung (AMZ), a catalogue of almost 700 pieces of music which was intended to serve as a guide for drawing up the programmes for a wide range of events.

In his list Seidl first carefully sorted out the ‘enemy’ pieces, which in some cases was not a clear-cut matter. In particular Italian compositions turned out to be problematic, because Italy had initially declared war only on Austria-Hungary. In doubtful cases individual works were therefore marked by square brackets. When Italy became a ‘full enemy’ in 1916, the efforts to impose censorship became all the more stringent: even Italian markings in the scores were to be eliminated under the heading of ‘delousing’ German musical life.

In the catalogue preference was given to songs which reviled the enemy: in the case of Germany this meant in particular England and France, the hereditary enemy. The pieces which were outstandingly suitable were those which recalled previous victories against the enemy nations. One that turned out be a veritable ‘hit’ was Die Wacht am Rhein (The Watch in the Rhine). For example, one soldier wrote shortly before his death on the Marne in September 1914:

And then we crossed the venerable old river, thundering, roaring, with a thousand voices singing of the watch on the Rhine. … Do not be anxious, we are just doing our duty, one man just like the other. We won’t let anyone in. The watch on the Rhine stands firm and loyal.

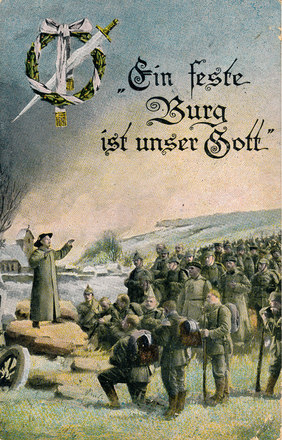

For religious worship, ceremonies of mourning and remembrance and when a more elevated note was to be struck, recourse was had to works of classical music. Here the list was headed by the sacred music of Johann Sebastian Bach, together with Beethoven (the third and fifth symphonies, Egmont, Fidelio), Liszt and Handel’s Hallelujah Chorus, while for Protestant gatherings there was Luther’s hymn Eine feste Burg ist unser Gott (A safe stronghold our God is still). For concerts representations of battles were enlisted, for example Liszt’s Hunnenschlacht (Battle of the Huns), as well as, of course, a large selection of marches. These works were, however, often subjected to questionable revisions, being drastically reduced to certain passages thought to be particularly useful or by being provided with new words.

For female audiences Seidl thought that those pieces were suitable which were directed explicitly at women, mothers and their sons, and were able, if required, to convey courage and consolation or to address the pain of leave-taking. What was considered particularly important in this respect were works which dealt with the topic of death and were intended to prepare wives and mothers for the death of their husbands and sons. Robert Stolz, who was otherwise rather to be allocated to the genre of operetta, set to music a poem by Alfred Grünwald entitled Die Mutter des Reservisten (The Mother of the Reservist), in which a mother takes leave of her son – accompanied by a melody in waltz rhythm.

In many compositions of this kind it was not so much the quality of the music which was to the fore; after all, according to Arthur Seidl in time of war aesthetic criteria had to take a back seat.

Translation: Leigh Bailey

Giesbrecht, Sabine: Musikalische Kriegsrüstung. Zur Funktion populärer Musik im 1. Weltkrieg, Gießen 2008. Unter: http://geb.uni-giessen.de/geb/volltexte/2008/5201/ (20.06.2014)

Tonaufnahme „Hunnenschlacht“ Franz Liszt. Unter: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pxrHFXP3p1Y (20.06.2014)

Tonaufnahme „3. Symphonie (Eroica)“ Ludwig van Beethoven. Unter: https://musopen.org/music/1033/ludwig-van-beethoven/symphony-no3-in-e-fl... (20.06.2014)

Quotes:

"delousing": NZfM Jg. 82, Teil I, 1915 und NZfM Jg. 83, Teil II, 1916, 277ff., zitiert nach: Giesbrecht, Sabine: Musikalische Kriegsrüstung. Zur Funktion populärer Musik im 1. Weltkrieg, Gießen 2008, 164. Unter: http://geb.uni-giessen.de/geb/volltexte/2008/5201/ (20.06.2014) (Translation)

„And then we crossed the venerable ...": Brief: Der deutsche Soldat. Briefe aus dem Weltkrieg, München 1921, 21f., zitiert nach: Giesbrecht, Sabine: Musikalische Kriegsrüstung. Zur Funktion populärer Musik im 1. Weltkrieg, Gießen 2008, 169. Unter: http://geb.uni-giessen.de/geb/volltexte/2008/5201/ (20.06.2014) (Translation)

-

Chapters

- ‘Long jackets instead of Tailcoats’ – The Music Business in Times of Austerity

- Arousing Patriotic Sentiments in the Concert of Nations

- ‘In War the Muses Learn How to Serve’

- Serious Times – Serious Art

- ‘I’d like to dance, I’d like to shout for joy’ – Popular Music in the First World War

- ‘German Musical Life and How to Delouse It’ – Music for Use in the War

- ‘What the soldier in battle dress is singing now will be sung by the entire German people in rare unity.’ – Soldiers’ Songs as Collectors’ Items

- ‘It’s Hugo’s damned duty not to die for the fatherland before I’ve got my Act III.’ – Richard Strauss and the First World War

- Militarism and Terror Set to Music

- ‘La Victoire en chantant’ – The French chanson in the First World War

- Musical Innovations in the First World War

- Composers’ Fates: War, Death and the Longing for Peace and Overcoming Memories

- Star Composers and the Great War