Viva l’Italia! Italian irredentism and the Habsburg Monarchy

-

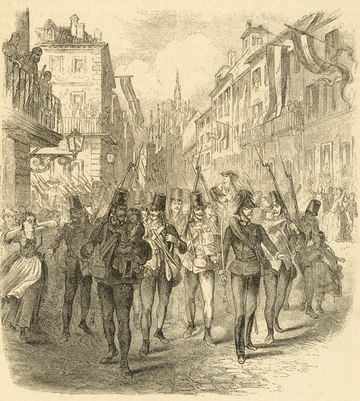

“The arrival of the imperial couple in Venice in 1856”, illustration, 1908

Copyright: Schloß Schönbrunn Kultur-und Betriebsges.m.b.H./Fotograf: Alexander E. Koller

-

The monument to Archduke Maximilian in Trieste, postcard, current in 1912

Copyright: Schloß Schönbrunn Kultur- und Betriebsges.m.b.H. / Objekt aus der Sammlung Dr. Lukan

The Habsburg presence in northern Italy was an important factor in the dynasty’s image as a ‘big player’ amongst the great European powers. However, the dynasty was dealt a number of bitter blows by the Risorgimento, the movement that finally brought about the forging of a unified Italian nation-state.

The Habsburgs had held sway in Italian-speaking areas since the fourteenth century, when their rule extended to the southern parts of the Tyrol and even then to Trieste. They constantly expanded their presence in the early modern period, at first principally through the initiative of the Spanish Habsburgs. The genesis of the Italian nation-state is closely linked to the presence of the Habsburgs in Lombardy and Venetia, which became part of the Austrian Empire at the Congress of Vienna. In addition the Habsburg sphere of influence also included the duchies of Tuscany and Modena, which were in the hands of collateral lines of the archducal house (secondogenitures).

As the nineteenth century progressed, the Habsburgs were confronted in all these lands by the Risorgimento’s ever-intensifying drive for Italian unification. One particularly important factor in this had been the period of Napoleonic rule in Italy, which saw the first partial overcoming of the long-standing political and dynastic fragmentation of the Italian-speaking world. Although the Napoleonic occupation was relatively short-lived, it aired the ideal of a unified Italy transcending all cultural and economic differences, which then became one of the foremost goals of the Italian national movement.

As the struggle for the Italian nation-state was a struggle for emancipation, its protagonists were naturally very receptive to revolutionary demands for civil and national liberties. They saw the authoritarian dynasties and polities into whose hands the Apennine peninsula had fallen as obstacles to the realization of the goal of a liberal constitutional nation-state. In the economically and culturally highly developed north, the Austrians were regarded as foreign rulers.

This is not to deny that the period of Austrian rule was a period of reform – even today northern Italians can be heard idealizing the old Austrian administration as the epitome of ‘buon governo’. By contrast with the administrators, however, the central government authorities in Vienna showed little awareness of local sensibilities. By installing foreign servants of the state they snubbed the local elites, though not so much on account of the latter’s pan-Italianism as of their fervent local patriotism. Initially, the northern Italian elites had not been disinclined to cooperate with Austrian rule. With their strong sense of regional identity, the Lombards and Venetians were principally concerned for their autonomy and not necessarily especially pan-Italian in their sentiments.

The mid-nineteenth century saw the House of Savoy’s kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont develop into the germ cell of Italian unification. This rising state had by this time occupied a position between the great powers and was a force to be reckoned with in the region. As such it was well-positioned to become the driving force in the movement for the unification of the Apennine peninsula. The political mastermind in this development was the statesman Camillo Conte di Cavour (1810–1861), who enlisted French support for military policies directed against Austrian rule.

In the face of internal and external opposition, Austria was only capable of preserving its position of power in northern Italy through the maintenance of a strong military presence, which was a hugely expensive enterprise. As a result the diplomatically isolated and internally weakened Habsburg Monarchy soon began to forfeit its supremacy. For Emperor Franz Joseph the loss of the rich northern Italian provinces of Lombardy and Venetia (in 1859 and 1866 respectively) constituted an ominous defeat and shook his neo-absolutist regime to its very foundations.

In the Italian-speaking areas still under Habsburg rule, namely the southernmost part of the Tyrol and the Litoral, the Austrian administration was now confronted with an additional element in the political opposition: ‘irredentism’, that is to say, the desire for the national ‘redemption’ of the Italians still living under non-Italian rule, which became the battle cry of the Kingdom of Italy after its proclamation in 1861. After the Papal state had been incorporated into the new nation-state of Italy, the Italian nationalists’ maximal demand extended not only to the whole Adriatic coast including Istria and Dalmatia but also to the southern side of the Alps, thus encroaching on historic core territories of the Habsburg Monarchy.

In the southernmost part of the Tyrol the representatives of the Italian-speakers were divided on the matter of whether to heed the call of their historic identity as Tyroleans or the desire to be united with the new Italian nation-state. In the rural areas of the Trentino, for example, where the majority of the population were conservative Catholics, sentiments were thoroughly pro-Austrian. Only with the general radicalization of nationalist agitation in the 1890s did Italian irredentism gain more sympathizers. The extent of the deterioration in relations between the German and the Italian nationalists was shown in the riots of 1904 following the opening of an Italian faculty of law at the university of Innsbruck, when there were large-scale demonstrations on the streets of the Tyrolean capital and attacks on Italian institutions and businesses.

Translation: Peter John Nicholson

Blaas, Richard: Die italienische Frage und das österreichische Parlament 1859–1879, in: Mitteilungen des Österreichischen Staatsarchivs 22 (1969), 151–245

Rumpler, Helmut: Eine Chance für Mitteleuropa. Bürgerliche Emanzipation und Staatsverfall in der Habsburgermonarchie [Österreichische Geschichte 1804–1914, hrsg. von Herwig Wolfram], Wien 2005

Corsini, Umberto: Die Italiener, in: Wandruszka, Adam/Urbanitsch, Peter (Hrsg.): Die Habsburgermonarchie 1848–1918, Band III: Die Völker des Reiches, Wien 1980, Teilband 2, 839–879

-

Chapters

-

Chapters

- The drive for unification

- The radical German nationalists and their attitude to the Habsburg Monarchy

- The concept of ‘German Central Europe’

- Together we are strong: Pan-slavism and "Slavdom"

- The rise and fall of Austro-Slavism

- "Two branches of one nation" – Czechoslovakism as a political programme

- Viva l’Italia! Italian irredentism and the Habsburg Monarchy

- From Illyrism to Yugoslavism: competing concepts for a southern Slav nation

- Élyen a Magyar – long live the Magyars! Hungarian Magyarization policy