Total mobilisation – the First World War and special measures

The First World War and the special measures announced in connection with it led to a hitherto unseen level of militarisation. Basic civil rights were considerably reduced, public opinion was subject to censorship and propaganda, economic and administrative competences were shifted to the military authorities, and military justice was extended to civilian affairs.

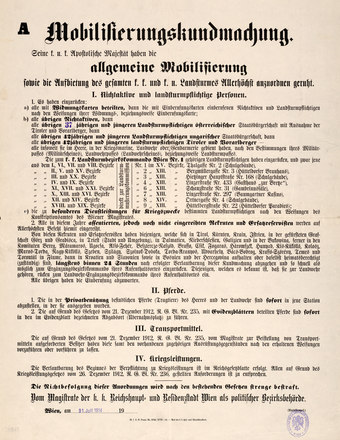

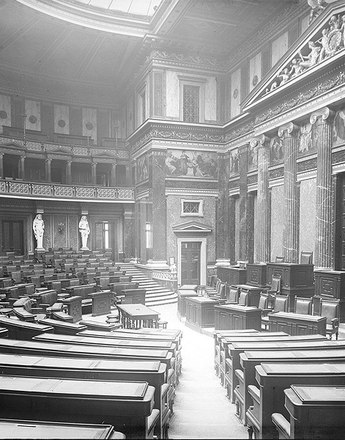

Mobilisation in the Danube Monarchy in July 1914 was accompanied by the introduction of special measures (“Ausnahmeverfügungen”), which had fateful consequences for society. The military authorities were granted a series of administrative and economic competences leading to a drastic reduction in fundamental civil rights. With the suspension of the Reichsrat in Vienna, the Austrian half of the empire was particularly affected. Whereas the Hungarian Diet continued to meet, the Austrian half of the empire was ruled between March 1914 and May 1917 without any parliamentary control. The Stürgkh government did not benefit from this situation, however. Because of the lack of political legitimation, it quickly ceded power to the military authorities, and the competence of the military administration was extended. Its direct influence was felt not only at the front but also in many areas back home. "Unlike the Hungarian half of the empire," says Christoph Tepperberg, "the situation in Austria until 1917 resembled that of a military dictatorship."

A number of military institutions were instrumental in the establishment of this quasi-dictatorship. The Military Oversight Department (“Kriegsüberwachungsamt” [KÜA]) ensured that the special measures were implemented in the various departments and authorities. The Ministry of War (“Kriegsministerium” [KM]) – was responsible for the war economy, and the Austro-Hungarian Army High Command (“k. u. k. Armeeoberkommando” [AOK]) – expanded its authority from the front to many other areas as well. The commanders-in-chief (“Höchstkommandierende”) of the AOK had the same right to issue orders and regulations as a provincial governor. From the start of the war, commanders-in-chief were appointed in Dalmatia, Galicia, Bukovina and parts of Silesia and Moravia. After Italy entered the war, this system of military governance was also extended to Vorarlberg, Tyrol, Salzburg, Styria, Carinthia, Carniola, Gorizia, Gradiska and Trieste.

As a result of the special measures in 1914, military justice was also applied to areas of civilian life, in particular to offences such as high treason, capital offences against members of the military, abetment to desertion, threatening officials, lèse majesté and disturbing the peace. A notable feature of military justice was the severity of sentences, which now also applied to civilians. Apart from the offences listed above, military justice also applied when civil courts were no longer available because of the war. All men working in the armaments and military transport industries were also subject to it and to the extremely severe military disciplinary code.

The penetration by the military into more and more areas of public life would not have been possible without a massive development of the necessary infrastructure. More and more people were employed in the new departments, so the Ministry of War, which had moved into new premises on Stubenring in 1913, had to rent over 80 additional rooms.

Translation: Nick Somers

Tepperberg, Christoph: Totalisierung des Krieges und Militarisierung der Zivilgesellschaft. Militärbürokratie und Militärjustitz im Hinterland, Das Beispiel Wien, in: Pfoser, Alfred/Weigl, Andreas (Hrsg.): Im Epizentrum des Zusammenbruchs. Wien im Ersten Weltkrieg, Wien 2013, 264-273

Quotes:

„Unlike the Hungarian half of the empire...": Tepperberg, Christoph: Totalisierung des Krieges und Militarisierung der Zivilgesellschaft. Militärbürokratie und Militärjustitz im Hinterland, Das Beispiel Wien, in: Pfoser, Alfred/Weigl, Andreas (Hrsg.): Im Epizentrum des Zusammenbruchs. Wien im Ersten Weltkrieg, Wien 2013, 272 (Translation)

-

Chapters

- Militarisation and nation-building: an interaction

- From the Theresian reforms to the battle of Königgrätz

- Universal conscription as the fundamental militarisation of society

- Military training: violence as a military instrument for achieving obedience

- Suicide, questions in parliament and pathological military discourse

- Anti-militarism in Bohemia: “The fit are enslaved”

- Total mobilisation – the First World War and special measures