While the events in Prague were catapulting the country into a historic new phase, the home team of leaders was in Geneva to discuss further steps towards independence with the general secretary of the exiled Czechoslovakian National Council, Edvard Beneš. It was only by reading the newspapers that these gentlemen first learned that an independent Czechoslovakia had been proclaimed in Prague.

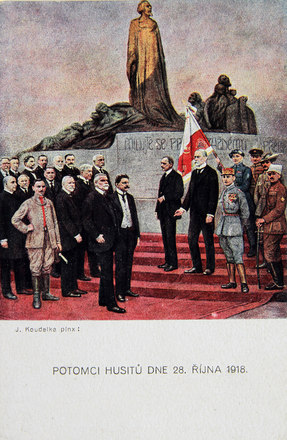

Nevertheless, it was impossible to gauge the whole scope of the coup in Prague from the first fragmentary reports. The political leaders sojourning abroad were still under the impression that people would wait for their return before proclaiming independence. When they finally realised that the coup had taken place, the Geneva Resolution was drawn up as a reaction to the Prague fait accompli, announcing the founding of a republic with Masaryk at its head. The political team of leaders first returned on 2 November, Masaryk did not arrive until December. His entry into Prague was nothing less than a triumphal procession.

The provisional Czechoslovakian National Assembly met for the first time on 14 November 1918. Their first resolution was to declare the House of Habsburg as deposed. German delegates were already absent from this body, for on 29 October they had proclaimed the annexation of the German-speaking regions of Bohemian territories to German-Austria and had gone into exile in Vienna.

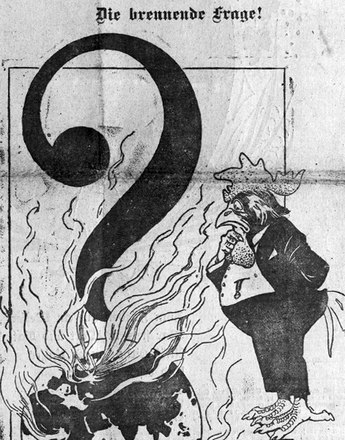

The German-speaking parts of Bohemia and Moravia that were to be annexed to the young nation of German-Austria formed a wreath around core Czech territory and contained linguistic islands besides which were likewise claimed as German-Austrian national territory. The proclamation of a Province of German-Bohemia with Reichenberg (Czech Liberec) as the capital as was not accepted by Czechoslovakia, since Prague insisted on the historical state borders. Separatist actions in the German-speaking regions were suppressed with military violence in 1918/19, claiming a number of dead. There was also a similar armed conflict with Poland about territories surrounding Teschen (Czech Těšín, Polish Cieszyn) in former Austrian Silesia, which eventually led to a partition of the disputed regions.

These in part violent conflicts exposed the different interpretations of the principle of national self-determination, which at the time was an omnipresent political slogan. In Czech, respectively Czechoslovakian argumentation, the territorial claims revealed a certain inner contradiction. Namely, in the case of the Bohemian lands, Prague insisted on the historical tradition of the Bohemian constitutional law and the immunity of the historical borders, even if they did not accord with the ethnic situation. Slovakia, however, had no constitutional traditions in retrospect, so here the argument was based on the right of national self-determination which would legitimise the detachment of the claimed regions from the historic Kingdom of Hungary.

Translation: Abigail Prohaska

Bihl, Wolfdieter: Der Erste Weltkrieg 1914–1918. Chronik – Daten – Fakten, Wien/Köln/Weimar 2010

Hoensch, Jörg K.: Geschichte Böhmens. Von der slavischen Landnahme bis ins 20. Jahrhundert, München 1987

Křen, Jan: Dvě století střední Evropy [Zwei Jahrhunderte Mitteleuropas], Praha 2005

Kučera, Rudolf: Muži října 1918. Osudy aktérů vzniku Republiky Československé [Die Männer des Oktobers 1918. Schicksale der Akteure der Entstehung der Tschechoslowakischen Republik], Praha 2011

Pacner, Karel: Osudové okamžiky Československa [Schicksalhafte Momente der Tschechoslowakei] (3. Aufl.), Praha 2012

Šedivý, Ivan: Češi, České země a velká válka 1914–1918 [Die Tschechen, die Böhmischen Länder und der Große Krieg 1914–1918], Praha 2001

-

Chapters

- Delenda Austria – Austria must be destroyed!

- The aim of state independence: from Utopia to a programme for the masses

- Preparing for the Coup

- The Day of the Coup: 28 October 1918

- The Founding of Czechoslovakia

- The Czechoslovakian Republic as Successor State to Austria-Hungary

- The Czechoslovakian Legions

- The Fall of the Symbols of Habsburg Rule