‘Black Decay’ – Soldiers as Victims

In Austrian literature the devastating effects of the war on individual men and on the condition of military masculinity are major themes. Writers confront the aspect of war as a merciless ‘engineer’ who mows down men or turns them into invalids.

In the evening the autumnal woods resound

With deadly weapons, the golden plains

And blue lakes, over them the sun

Rolls grimly away; the night envelops

Dying warriors, the savage lament

Of their smashed mouths.

But silently on the pastures

Red clouds gather, therein lives a raging god,

The spilled blood, the moonly cool;

All roads lead to black decay.

Under the golden branches of the night and stars

The shadow of the nurse sways through the silent grove,

To greet the spirits of the heroes, the bleeding heads;

And softly in the reeds sound the dark flutes of autumn.

O prouder grief! You iron altars,

Today the hot flame of the spirit is fed by an immense pain,

The unborn grandchildren.

War appears as a decisive experience that makes masculinity a problematic concept and condemns men to becoming physically and mentally immobile, weak and unfit for life. The suffering and dying, or the condition of being marionettes without any will of their own and unable to influence events, stands in drastic contrast to the glorious fate of the ‘heroes’ as it is narrated or created by writers with a nationalistic stance.

Even in the early months of the war it becomes increasingly apparent that the Great War is a disastrous experience for men. Everyday life in war and at the front does not in the least correspond to the male fantasy of a privileged adventure reserved for men. It is a massacre of men who wanted to be heroes. To be humiliated, wounded, destroyed: this is a collective fate that gives rise to a community of suffering among the victims.

In Stefan Zweig’s poem Der Krüppel (The Cripple) (1915) a maimed soldier gets help and solace from his sympathetic comrades. They try to encourage him, bring him food, comfort him: ‘Oh how gentle and good everything was now. How brotherly the world which surrounded him, the cripple. How different from that other one from which, looking back, he had come.’ On the other hand the war wounded depicted in literary texts feel lonely, abandoned, marginalized, as in Albert Ehrenstein’s poem Dem ermordeten Bruder (To the Murdered Brother) (1917), in which one of the compulsory heroes falls ill, is classified as a malingerer and finally dies – a ‘moth captured in the web of war’. One of the best known depictions of the soldier’s death is the image of ‘black decay’ presented by Georg Trakl in his poem Grodek, which talks of the ‘spirits of the heroes’ and formulates a lament for the warriors dying in the inferno of a battle of equipment and materials.

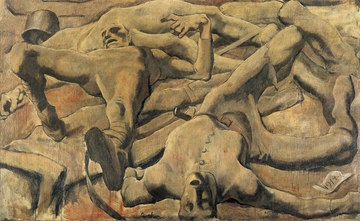

Drastic images of soldiers as victims are found in Andreas Latzko’s volume of stories Menschen im Krieg (Humans in the War) (1917). Banned in Germany and Austria, it was published in Zürich in Switzerland. Latzko describes the war as a ‘factory for cripples and corpses’, in which men fall into a ‘closely woven web of steel and lead’ and are disfigured until they are unrecognisable. The fragmented male body stands in drastic contrast to the nationalistic fantasies of wholeness and an intact community of men.

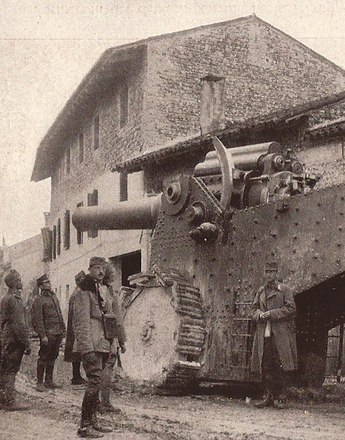

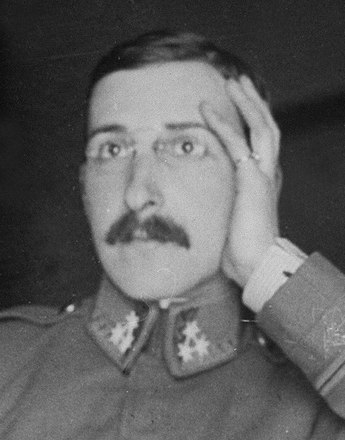

In his journal Soldat im Prager Korps (Soldier in the Prague Corps) (1922), which is better known under the title Schreib das auf, Kisch! (Write That Down, Kisch!), Egon Erwin Kisch, a writer who took part in the war, assesses the stages of his involvement in the war, which he always judges critically. His male wartime adventure appears as unromantic and unheroic. His own activities are in no way presented as heroic deeds but as strategies to numb anxiety, horror and despair. Kisch records an ever increasing number of dead and wounded, the suffering of the soldiers and the arrogance of the officers. Eventually he is wounded and in the end decides to leave the service: ‘I shall lie in bed and read books, and perhaps I shall kiss girls, sit in the café and talk to friends … .’ In many literary texts forms of military masculinity reach their limits and in the face of the technology of destructive weaponry cannot be kept up from either an ideological or a physical and mental perspective.

Translation: Leigh Bailey

Barker, Andrew: „Ein Schrei, vor dem kunstrichterliche Einwendungen gern verstummen“ – Andreas Latzko: Menschen im Krieg (1917), in: Schneider, Thomas F./ Wagener, Hans (Hrsg.): Von Richthofen bis Remarque. Deutschsprachige Prosa zum 1. Weltkrieg, Amsterdam/New York 2003, 85-96

Leisch-Prost, Edith/Pawlowsky, Verena: Kriegsinvalide und ihre Versorgung in Österreich nach dem Ersten Weltkrieg, in: Kuprian, Hermann J. W./Überegger, Oswald (Hrsg.): Der Erste Weltkrieg im Alpenraum. Erfahrung, Deutung, Erinnerung. Innsbruck 2006, 367-380

Patka, Marcus G.: Egon Erwin Kisch. Stationen im Leben eines streitbaren Autors, Wien/Köln/Weimar 1997

-

Chapters

- Dreamers Who Turn into Heroes

- ‘Warriors on the Frozen Front’ – The War in the Alps as a Test of Manly Strengths

- The War as a ‘Technoromantic Adventure’

- Forms of Masculinity – Hierarchies, Rivals, Competitors

- Melancholy Men in Uniform – How Masculinity Becomes a Problem

- ‘Black Decay’ – Soldiers as Victims

- ‘The Flight Without End’? – The Warrior’s Homecoming

- ‘A New Race of Men’? – Ideologies of Masculinity in Post-War Austria