The War as a ‘Technoromantic Adventure’

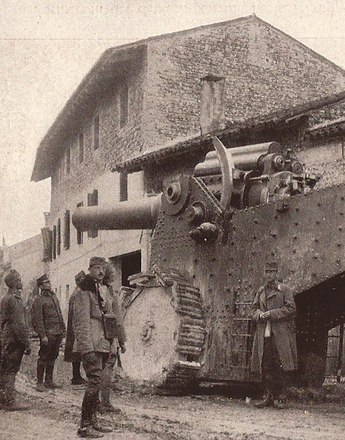

Karl Kraus has given an apt summary of the way in which mechanized warfare provided new conditions for the demonstration of heroic forms of behaviour and the loss of manly and militaristic attitudes. He describes the First World War as a ‘technoromantic adventure’, in which courage has become entangled with technology and confrontations on the basis of muscle power have become obsolete.

The fate of soldiers is decided by the ‘chance of being hit by a mine, a bomb or a torpedo’. Although the old military concept of honour has lost much of its meaning in ‘chlorious’ confrontations and it is only a matter of ‘the effectiveness of each side’s chemistry’, the old ideology which has still not been shaken off glorifies traditional values and ideals of masculinity such as a colourful uniform ‘and the duty to place one’s hand against one’s forehead when a superior comes into view’. Kraus makes fun of the way in which the ‘immortal’ ideology still invokes the ‘confrontations on the basis of muscle power’ and attempts to find a place for discipline and honour and a game played with medieval rules in the midst of ‘filth and misery’.

Irrespective of the way in which warfare has become mechanized, the heroic and martial ideal of masculinity is still taken up not only in propaganda and the legend-forming reports of those involved in the war but also in art and literature. In line with Karl Kraus’s diagnosis Austrian literature presents ‘technoromantic adventures’. On the one hand these are intensified into aggressive nationalism, as in Bodo Kaltenboeck’s Armee im Schatten (Army in the Shadow) (1932) and various representations of the battles on the Isonzo front, while on the other they present a nostalgically emotional story in which the experience of war is reduced to seducing women and making use of symbols and rituals.

In Alexander Lernet-Holenia’s novel Die Standarte (The Standard) (1934), one of the best known examples of military nostalgia, the splendour of the officer’s former code of honour is rehabilitated as ‘the Habsburg myth’, as Claudio Magris calls it. The narrative is centred on an officer loyal to the emperor who guards the standard even when there is a mutiny in the regiment, the army disbands itself and the Habsburg monarchy comes to an end: ‘But in the end I would touch the brocade as if I was touching the locks of a bride’s hair … .’ When he flees to Vienna he is accompanied by a woman who, as it were, competes with the flag. In the end he throws the standard into the fire and returns to his partner, who remains as his only support in the ruins of a world which he considered to be indestructible. The gallant officer with his loyalty to the emperor wavers between the conquest of women and the eroticism of the flag. Lernet-Holenia creates a type of masculinity rooted in the aristocracy and the cavalry which does not represent an aggressive form of virility and does not really correspond to the qualities of the tough warrior. In his wartime universe it is the woman who eventually conquers a prominent place for herself, but after the war the former officer cannot completely surrender to the civilian way of family and married life. He finds friends in the male social network of veterans and keeps up his search for his military past and representations of it.

Translation: Leigh Bailey

Eicher, Thomas: Das Heimkehrermotiv in Lernet-Holenias „Standarte“. Zu einem literarischen Topos der Zwischenkriegszeit, in: Eicher, Thomas/Gruber, Bettina (Hrsg.): Alexander Lernet-Holenia. Poesie auf dem Boulevard, Köln/Weimar/Wien 1999, 113-130

Theel, Robert: „Die Maschine hat den Helden getötet“. Beobachtungen zu direkten und indirekten Verwendungen des Mentalitätsbegriffs in fiktionalen und essayistischen Texten vor und während des 1. Weltkrieges im Hinblick auf den Heroismusbegriff (Nowak, Soyka, Kraus, Unruh, Marinetti, Rilke), in: Krieg und Literatur/War and Literature 9 (1993), 97-118

-

Chapters

- Dreamers Who Turn into Heroes

- ‘Warriors on the Frozen Front’ – The War in the Alps as a Test of Manly Strengths

- The War as a ‘Technoromantic Adventure’

- Forms of Masculinity – Hierarchies, Rivals, Competitors

- Melancholy Men in Uniform – How Masculinity Becomes a Problem

- ‘Black Decay’ – Soldiers as Victims

- ‘The Flight Without End’? – The Warrior’s Homecoming

- ‘A New Race of Men’? – Ideologies of Masculinity in Post-War Austria