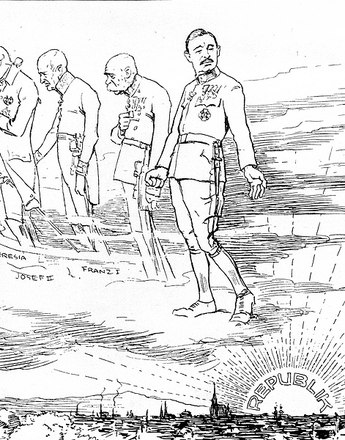

The Austro-Hungarian Monarchy had a diversity of religions, and the Emperor’s subjects included Catholics, Protestants, orthodox Christians, Jews and Muslims. Except for the Catholic Church, however, religious groups were practically absent from the Austro-Hungarian pictorial canon.

The Catholic Church was a fundamental pillar closely connected with the house of Habsburg. In spite of a few anti-clerical laws in the second half of the nineteenth century, there was no strong liberal movement critical of religion. Throne and Church formed a unit. Through his presence at the Corpus Christi processions or his patronage of the International Eucharistic Conference in Vienna in 1912, the Emperor symbolized this alliance. It was also underpinned by the membership of the various religions. Austria was a Catholic country: according to the 1910 census, 79 per cent of the inhabitants of the western half of the Danube Monarchy were Catholic, and the proportion was even higher in the Alpine regions.

Whereas films exist of the Catholic liturgy, the other religious groups in the Monarchy are practically absent from the cinematic canon – be it the Protestant minorities among the Hungarians and Slovaks or the orthodox Christians, Jews and Muslims in the border areas, Galicia, Transylvania, Bosnia and Herzegovina. There are few films like the imposing Emperor Franz Joseph in Sarajevo: a Journey Through Bosnia and Herzegovina (A 1910) showing the confessional pluralism of the Habsburg empire. In this film groups of Christian and Muslim children pay tribute to the aged monarch.

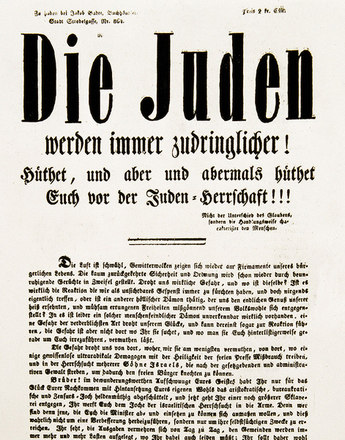

Although accounting for only 3 per cent of the population of the later Republic of Austria, Jews, particularly in the cities, made an important contribution to economic and intellectual life. The integration of Jews since the reforms of Joseph II was an important factor in the development of an innovative culture. The mainstream population reacted with prejudice and resentment nourished by traditional beliefs, fear of modernization, biological racist views and ideas of ethnic nationalism. The growing anti-Semitism fostered mainly by the Christian Socialist and German Nationalist groups was directed against small traders and representatives of orthodox communities, who corresponded to the stereotypical image. Galician ‘Ostjuden’ were singled out particularly as scapegoats after 1914. They were unjustly accused of responsibility for the disastrous consequences of the First World War. The example from the film Types and Scenes from Viennese Popular Life (A 1911) is an early example of anti-Semitism: a Jewish trader is contemptuously ordered away from the table.

Translation: Nick Somers

Hanisch, Ernst: Der lange Schatten des Staates. Österreichische Gesellschaftspolitik im 20. Jahrhundert, Wien 1994

Leidinger, Hannes/Moritz, Verena/Moser, Karin: Österreich Box 1: 1896-1918. Das Ende der Donaumonarchie, Wien 2010

-

Chapters

- Imperial and Royal myth in film

- Presentation of the imperial household: pictorial icons

- What the films didn’t show 1: Social contrasts

- What the films didn’t show 2: Religious diversity

- What the films didn’t show 3: nationalist conflicts

- Lack of resources and wartime financial difficulties on film

- Film documents: after the disaster