Bureaucracy one was one of the most important pillars of the Austrian authoritarian state. The language of red tape was therefore a hotly disputed political issue.

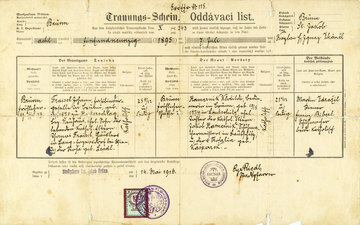

In the Imperial-Royal administration, a distinction was made between the internal official language, i.e. the language used by an authority for its internal communications, and the external official language, in which the contact between the authority and the citizens was conducted.

Once again, disputes arose in the Bohemian Lands, core territories of the Monarchy where two language groups with highly marked national feelings in the form of the Germans and the Czechs faced each other with an increasing reluctance to compromise. The dispute between the Czech majority population and the large German minority over the question of the language of the administration developed into a alarming state crisis.

In the Bohemian Lands, German was the internal official language, while Czech was initially only recognised regionally as an external official language in those parts of the country with a clear Czech majority, while dealings with the authorities in German were possible throughout the country.

In 1880, the language demands of the increasingly confident Czech majority population in Bohemia, following their rapid cultural and economic advancement, could no longer be ignored. The Taaffe government, resisting the protests of the German Bohemians, succeeded in having Czech recognised as a customary language alongside German throughout Bohemia and Moravia. Thus official dealings were to be conducted in the language of the document submitted to the authority by the citizen. Even overwhelmingly German districts were now required to ensure that dealings with the authorities could be in Czech, which had a strong signal effect in the originally German-speaking industrial regions of Northern Bohemia, where the huge influx of workers meant that the Czech share of the population was continually increasing. However, the internal official language remained German throughout the country.

An even greater furore was caused by the controversy surrounding the language regulation that Minister-President Count Badeni attempted to enforce in 1897. In order to gain the support of the Czech members of the Diet for his government programme, he proposed a complete equal status for the two national languages as internal and external official languages. This would have de facto required all civil servants to be bilingual, which would have involved giving preferential treatment to the Czechs, since as a rule they were also capable of speaking German. In contrast, most German-speakers of Bohemia had hardly any knowledge of the second language of the Land, and were often unwilling to learn it. This was the expression of a deep-rooted sense of superiority on the part of the Germans over the Slavs in general and a lack of respect and serious lack of understanding for their Czech compatriots. But this attempt ultimately failed in the face of the huge wave of protests set off by German national circles throughout the Monarchy. As a reaction, Czech national agitation began to openly oppose the Habsburg Monarchy.

However, the question of the language of the administration also held considerable potential for conflict in other parts of the Empire. In 1882, Galicia was the focus of controversy concerning the use of the Cyrillic alphabet in official correspondence. Although Ruthenian was recognised as a language of the Land, it was only permitted in Latin script. The increasingly strong Ruthenian national movement began to take measures against Polonisation, which they felt lay behind the obligation to use the Latin alphabet. Petitions in Cyrillic script having been refused, an appeal was filed with the Imperial Court (corresponds to today's Constitutional Court), which held that submissions in Cyrillic script had to be accepted in accordance with the constitutionally established principle of national equality.

It was likewise by means of litigation before the Imperial Court that the Croatian-speaking majority population of the Adriatic island of Krk (Croatian)/Veglia (Italian) succeeded in 1888 in forcing the local authorities under Italian domination to offer official dealings in Croatian as well.

Translation: David Wright

Hoensch, Jörg K.: Geschichte Böhmens. Von der slavischen Landnahme bis ins 20. Jahrhundert, München 1987

Křen, Jan: Die Konfliktgemeinschaft. Tschechen und Deutsche in den böhmischen Ländern 1780–1918 (Veröffentlichungen des Collegium Carolinum 71), München 1995

Stourzh, Gerald: Die Gleichberechtigung der Nationalitäten in der Verfassung und Verwaltung Österreichs 1848 bis 1918, Wien 1985

Wolf, Michaela: Die vielsprachige Seele Kakaniens. Übersetzer und Dolmetscher in der Habsburgermonarchie 1848 bis 1918, Wien u. a. 2012