In the study of the history of the nineteenth century, which concentrated above all on the history of states, the Slovenes, who did not have a state of their own, were regarded as being ‘without history’.

The Slovenian language group suffered from an absence of elites, as the local nobility and urban propertied classes in the Slovenian settlement areas were German or Italian speakers. These elite languages dominated administration and literature for a long time, while Slovenian was spoken in the smaller towns and villages. The Catholic clergy therefore played a particular role as custodians of a Slovenian language awareness, as religious writing had long been the only written literature in the vernacular.

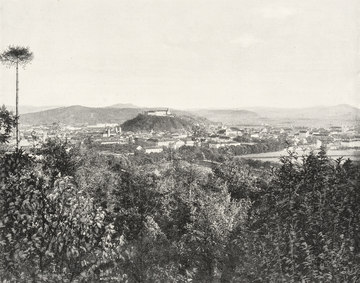

A Slovene proto-national awareness existed above all in the Duchy of Carniola. In spite of the dominance of German, Carnolians in the early modern era identified themselves through their mastery of the vernacular, which was Slovenian. The national awareness of the Carniolian estates led to an early study of the region. Mention should be made in particular of the work of the Baroque historian Johann Weichard Valvasor (1641–93), who undertook a detailed survey of the region.

The emergence of a modern Slovene nation began, as with most ethnic groups in central Europe, in the early nineteenth century. A leading role in this regard was played by Jernej Bartol Kopitar (1780–1844), who was head of the manuscripts department of the Vienna Court Library. An outstanding philologist, he wrote the first modern Slovenian grammar (Grammatik der slawischen Sprache in Krain, Kärnten und Steiermark, 1808), whose title already pointed the way to nationhood. Kopitar saw himself less as a Slovene in the modern sense but rather as a Slav. He promoted Old Church Slavonic – created by the ‘Slav apostles’ Cyril and Methodus in the early Middle Ages as a liturgical language as part of the Christianization of the Pannonian Slavs – as the authentic Slavic language that would unite all Slavs. Kopitar collected Old Slavonic documents and saw the archaic Slovenian language as the guardian of Old Slavonic forms.

The pioneers of Slovene nationhood also created an ideological national history. An important historical point of reference was found in the early medieval duchy of Carantania peopled by Alpine Slavs, which was blown up in legend to become the early ‘Slovene nation state’.

The Napoleonic Wars gave further stimulus to the formation of a national identity. Apart from the general influence of the ideas of the French Revolution with its emphasis on the sovereignty of the people, the creation of the Napoleonic Illyrian Provinces marked a turning point. For the first time – if only for a few years – the southern Slavs were territorially unified. The long germination of a southern Slav awareness led to the ideology of the Illyrian movement, which sought the amalgamation to a great southern Slav nation with long-term aim of national independence.

Translation: Nick Somers

Pleterski, Janko: Die Slowenen, in: Wandruszka, Adam/Urbanitsch, Peter (Hrsg.): Die Habsburgermonarchie 1848–1918, Band III: Die Völker des Reiches, Wien 1980, Teilband 2, 801–838

Rumpler, Helmut: Eine Chance für Mitteleuropa. Bürgerliche Emanzipation und Staatsverfall in der Habsburgermonarchie [Österreichische Geschichte 1804–1914, hrsg. von Herwig Wolfram], Wien 2005

Štih, Peter/Simoniti, Vasko/Vodopivec, Peter: Slowenische Geschichte. Gesellschaft – Politik – Kultur, Graz 2008