Power and the public: political movements in historical films

Towards the end of the nineteenth century, popular political parties began to form in the German-speaking part of the Monarchy: Social Democrats, Christian Socialists and German Nationalists. They gradually began to make their appearance in documentary films and newsreels in Austria-Hungary.

In the course of the election reforms leading in the western half of the Danube Monarchy in 1907 to ‘universal, equal, secret and direct’ suffrage for men, the base for political decision-making became much broader. This development was accompanied by the formation of political parties for the masses. The Emperor’s German-speaking subjects were offered three competing ideologies: Social Democrats, German Nationalist and Christian Socialists.

The political parties were not central to the cinematic canon of the Habsburg Monarchy, and international production companies commissioned camera teams to film events with a party political background only when they were exceptional or violent. One such case, which showed the crass differences between the parties, was the assassination of the Social Democratic workers’ leader Franz Schuhmeier in 1913. The workers assembled at his funeral to demonstrate their solidarity and importance as a political force. A political counterculture was emerging and was later also to be captured on film (The Funeral of the Reichtag Member Franz Schuhmeier, A/F 1913). This politically motivated act of violence by Paul Kunschak, brother of the Christian Socialist party functionary Leopold Kunschak, remained an exception for the time being. The conflict between Christian and Marxist ideas escalated after 1918 to replace the ethnic disputes that had dominated until then.

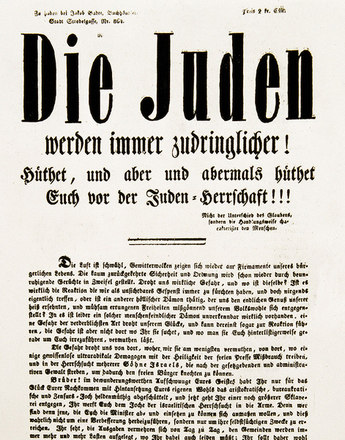

The most well-known politically elected personality at the turn of the century, a politician who still remains contentious today, was without a doubt Vienna mayor Karl Lueger, whose political manifesto was based on anti-capitalist, anti-Semitic and anti-liberal ideas. Lueger, who came from a petty bourgeois background, had a populist appeal and a reliable feeling for the mood of the electors. He told them what they wanted to hear. The charismatic speaker was able to win over the disgruntled man in the street by pointing the finger at those who were to blame: the aristocracy, ‘Jewish’ academics and bankers, the ‘Ostjuden’ and finally the Social Democrats, ‘protectors of the Jews’. For Lueger anti-Semitism was above all a means to an end, an instrument with which to speak to the masses, but his speeches kindled deeply felt resentments. His progressive urban development policies (gas, electricity and water supply, construction of swimming baths, schools and parks, establishing public transport and introducing a municipal burial service) turned Vienna into a modern metropolis, and he was adored as the ‘people’s emperor’ and ‘lord of Vienna’. His anti-Jewish populism also gave him the epithet ‘father of modern anti-Semitism’.

Two historical film documents are devoted to Lueger. One shows the mayor, already heavily marked by illness, on his 64th birthday surrounded by admirers and like-minded colleagues (Dr. Karl Lueger’s Birthday in 1908 in Lovrano, A 1908). His magnificent funeral in 1910 bears witness to his immense popularity. Black flags flew throughout the city, the funeral cortege was followed by over 1,000 carriages, and the streets were lined with people. The film-makers had realized the special nature of this show and with a touch of voyeurism were always around to film the final journey of aristocrats and emperors, politicians and artists. The nature of the event as a spectacle is evident from the decorations and entourage, mourners and spectators, watching and being watched. Many of these pictures, commissioned for the most part by the state but also privately, including The Burial of Vienna Mayor Dr. Karl Lueger in March 1910, are etched in the visual memory of the nation.

Translation: Nick Somers

Boyer, John W.: Karl Lueger (1844–1910). Christlichsoziale Politik als Beruf. Eine Biografie, Wien 2010

Hamann, Brigitte: Hitlers Wien. Lehrjahre eines Diktators, München 2001

Moser, Karin: Wien 1910: Karl Lueger und das andere Wien der Jahrhundertwende; in: filmarchiv, Nr. 68, Mai/Juni 2010, 52-55

-

Chapters

- Cinematic fascination: the machine in war propaganda

- Mobility in film: conquering new spaces

- The thrill of speed in film: heroes of the road and air

- Voyaging and travelling: tourism and tourism films

- Capturing the unusual: the Vienna Prater

- Movement in films – sport, gymnastics and physical culture

- Power and the public: political movements in historical films