Cinematic fascination: the machine in war propaganda

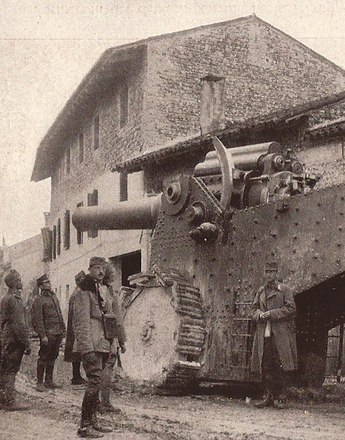

New sources of energy and power-driven machinery changed industrial production and work. The industrial promotion film soon developed as a genre, drawing attention to technical progress in general and in detail. Many films were made during the war showing the efficiency of the industrial war effort in Austria-Hungary.

As the nineteenth century came to a close, petroleum, gas and electricity as new sources of energy changed everyday life and work. Artificial light lengthened the day, and industrial production and working procedures underwent incisive changes. Modern power-driven machines were introduced, and smaller automatic work units were developed, heralding the conveyor-belt era. By the end of the nineteenth century mass production permitted standardization of complex assemblies such as bicycles, sewing machines and armaments.

At the same time, there was an increasing fascination with mobilization and mechanization. Modern production methods and new technical achievements were not only discussed by specialists but also made their way into films. The efficiency of the domestic economy was emphasized through pictures of industrial companies and their high-technology production methods. The films featured recurrent style elements of both a demonstrative and informative nature. Viewers were guided in their interpretation and understanding above all by explanatory title cards, which split up the recordings, organized the images and provided the desired interpretation. Most of the time they remained pragmatic, succinctly explaining the production processes being shown.

Industrial promotional films from the War Press Office offered a considered presentation of high-quality and precisely controlled manufacture of strategic products. The film Werdegang einer Soldatenmontur. Aufgenommen in den Spinnereien, Webereien und mechanischen Konfektionsfabriken der Firma Wilhelm Beck und Söhne [Manufacture of a soldier’s equipment filmed in the spinning, weaving and mechanical finishing shops of Wilhelm Beck and Sons] (A 1917), for example, sought to link history and tradition with the mechanized modern era. The film starts with copper engravings showing cloth-making in 1727 and is followed by industrial shots demonstrating the technical progress achieved since then. Long shots and close-ups of cogwheels, motors and conveyors suggest modern-day mechanized production. The film concentrates on the object being made and the machining process. The camera gradually zooms in on the machines, scanning them and showing the machining processes step by step. Hitherto hidden sights are made visible in this way.

Human manpower was still needed to change the bobbins, tension the threads and operate the levers, insert the cloth or finish the material with special sewing machines and presses, and full mechanization of the process was still a long way off. The theme of quality assurance is evident here as in so many industrial films during the war: raw materials, intermediate products and fabrics are continuously checked by skilled workers, and the finished product is inspected by high-ranking officers. The quality and value of the uniforms is emphasized in the final shot of a sentry taking up position in front of the clothing store.

Translation: Nick Somers

Eigner, Peter/Helige, Andrea (Hrsg.): Österreichische Wirtschafts- und Sozialgeschichte im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert, Wien/München 1999

Weitensfelder, Hubert: Technischer Wandel und Konsum im 19. und frühen 20. Jahrhundert, in: Breuss, Susanne/Eder, Franz X. (Hrsg.): Konsumieren in Österreich 19. und 20. Jahrhundert, Wien 2006, 105-123

-

Chapters

- Cinematic fascination: the machine in war propaganda

- Mobility in film: conquering new spaces

- The thrill of speed in film: heroes of the road and air

- Voyaging and travelling: tourism and tourism films

- Capturing the unusual: the Vienna Prater

- Movement in films – sport, gymnastics and physical culture

- Power and the public: political movements in historical films