On the eve of the First World War the political system in the Austrian half of the empire suffered a severe crisis, and there were several rapid changes of government at the start of the new century.

‘The Austrian parliament is the weakest in the civilized world if not in the world as a whole.’

Quoted from: Der Parlamentarismus. Sein Wesen und seine Entwicklung (Vienna, 1914), quoted in Hanisch, Ernst: ‘Der lange Schatten des Staates. Österreichische Gesellschaftsgeschichte im 20. Jahrhundert’ in Herwig Wolfram (ed.), Österreichische Geschichte 1890–1990 (Vienna, 2005), p. 230

Following the era of Minister-President Count Eduard Taffe from 1879 to 1893, who thanks to his strategy of ‘muddling through’ restricted government work to maintaining the status quo, and the overthrow of Minister-President Count Kasimir Badeni in 1897, there was a series of governments, few of which lasted more than one or two years. Between 1871 and 1917 there were twenty heads of government in Austria, compared with only five changes in government in Germany during the same period.

Just before the outbreak of the First World War, Minister-President Count Karl Stürgkh, who cultivated a very authoritarian style and also suspended the Reichsrat in 1914, managed to stay longer in the saddle, from 1911 to 1916. Following his assassination in October 1916, there were a further five governments in quick succession before the end of the Monarchy in October 1918.

One reason for the weakness of the governments of Cisleithania was that heads of government in the Reichsrat, who often operated with the slenderest of majorities, could not always count on support from the monarch. Franz Joseph, who effectively had the last word in political decisions, frequently abandoned his minister-presidents in crisis situations.

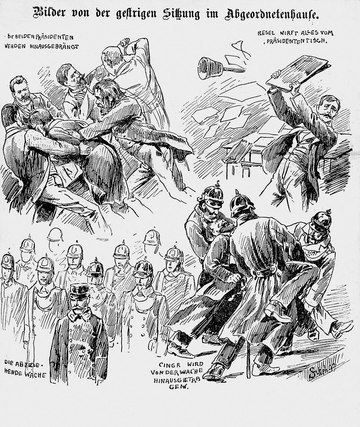

This meant that incisive reforms were avoided in favour of ad hoc solutions. Because of an absence of assertive political power, governments rarely played a constructive role but were propelled by the persistent and fundamental opposition of destructive extremists in the Reichsrat. Obstructionism was a popular means of opposition, ranging from passive resistance to physical confrontation. The irresponsible actions of parliamentarians to escalate the situation culminated in shouting matches, tumult and fist fights, often requiring police intervention to separate the squabbling members.

The governments also reacted with emergency decrees and other extreme measures. The emergency clause (paragraph 14 of the Constitution) allowed parliament to be bypassed when difficult and controversial decisions had to be made. This undermining of parliamentarianism was exacerbated by the harmful practice of deals between members of parliament and top bureaucrats away from interference by the opposition. This ‘art of intervention’, coupled with patronage and corruption, not to mention the Emperor’s authority as a form of leverage, did little to enhance the public face of parliamentarianism.

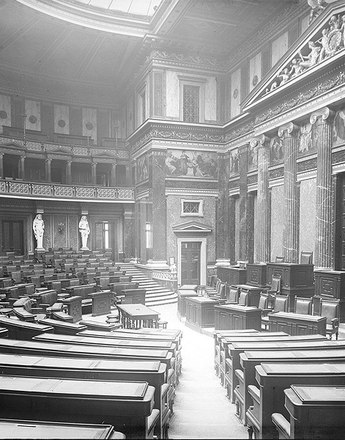

In March 1914 the crisis led to the dissolution of the Reichsrat. Parliament was adjourned and was not to be reconvened until 1917. During this time Austria was governed by a bureaucratic authoritarian regime. When war broke out the rule by top bureaucrats without parliamentary control was tantamount to a re-introduction of absolutism through the back door.

Sadly, this was not only accepted but also welcomed by much of the public on account of the catastrophic political culture of Austrian parliamentarianism. Respect for parliament, described by the media as a ‘charade’, was so low across the entire ideological spectrum that few people saw the need for popular representation at all.

Translation: Nick Somers

Hanisch, Ernst: Der lange Schatten des Staates. Österreichische Gesellschaftsgeschichte im 20. Jahrhundert [Österreichische Geschichte 1890–1990, hrsg. von Herwig Wolfram], Wien 2005

Rumpler, Helmut: Eine Chance für Mitteleuropa. Bürgerliche Emanzipation und Staatsverfall in der Habsburgermonarchie [Österreichische Geschichte 1804–1914, hrsg. von Herwig Wolfram], Wien 2005

Wandruszka, Adam (Hrsg.): Die Habsburgermonarchie 1848–1918, Band VII: Verfassung und Parlamentarismus. Teil 1: Verfassungsrecht, Verfassungswirklichkeit und zentrale Repräsentativkörperschaften, Wien 2000

-

Chapters

- ‘God preserve Him, God protect Him’ – The Emperor

- The Army: Austria-Hungary in its entirety

- The bureaucracy as the long arm of the state

- The Dual Monarchy: two states in a single empire

- ‘Indivisible and inseparable’ – the supranational state

- The Habsburg Monarchy in the process of democratization

- The absence of political culture

- A strong monarch and autocratic tendencies